Review by Graham Johnstone

The Science Service is the first graphic novel, by stylish illustrator and designer Rian Hughes. Actually, at just over thirty pages, bulked up by board covers, we should probably call it a graphic novella.

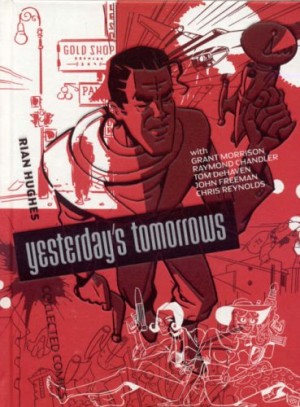

It’s also available in Hughes’ retrospective collection Yesterday’s Tomorrows – the title of which neatly sums up his trademark ‘retro-futurism’. His comics, illustrations and designs lovingly re-appropriate the styles and images of the past – particularly the decades either side of World War II and their visions of the future. A particular touchstone is the 1951 Festival of Britain, which promoted Britain’s contribution to technology and the arts, and through this aimed to instil the nation with a forward looking optimism for the post-war period.

When Hughes and writer John Freeman worked on this forty years later, Britain’s future looked rather less bright. Margaret Thatcher’s divisive government had been in place for a decade, and Britain enjoyed little of today’s tech. The government in the story, as in real life, were handing the country over to the commercial sector.

The setting is Britain 2051, just prior to the centenary New Festival of Britain. Freeman wisely avoids explaining everything, but The Science Service seems to have begun as a public service organisation, and somewhat lost its way. There’s a derisive reference to their production of the Mickey Mouse watches seen in the story – perhaps a symbol of Britain’s loss of cultural and economic leadership to the USA following WWII.

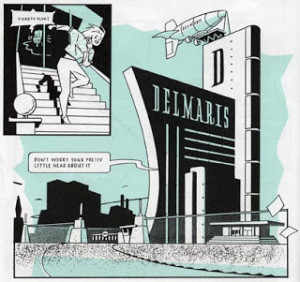

The protagonist, Henry van Goyen, worked years before on Imagon face-changing technology. He knows it had serious flaws, only lasting momentarily, and killing some users. Jethrik Kasten, had his face stuck in the image of an anthropomorphic cat – though it did his career no harm. Kasten’s now a TV news anchor about to interview the man opening the Festival – the smooth talking Herbert Spence of Delmaris Corp. Word is leaked that Delmaris are using the festival for a mass launch of a new version of Imagon, and for Henry and others this is a catastrophe they must try to avert.

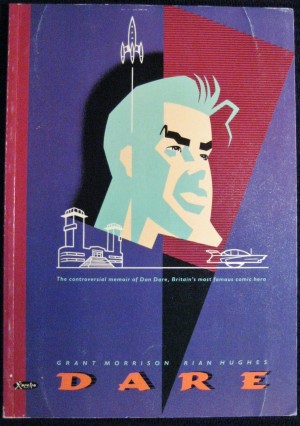

In many ways The Science Service pre-empts Hughes next vision of the future, Dare with writer Grant Morrison, although in that the (Thatcherite) government are the visible antagonist. The plots of the two books are similar, and Henry resembles Hughes’ depiction of Dan Dare.

This was Freeman’s first professional story, and there are some quirks. The characters we follow most closely are only peripherally involved in the climax, by then it feels slightly like Henry, the ostensible protagonist was only there to unpack the plot for the reader.

The story though is partly a vehicle for Hughes to draw this beautiful Art Deco inspired future. It opens with an image of a a space-age (think – Tintin’s moon rocket) airship floating tethered to an obelisk-like tower. Then there’s an underground train with an elegant power last seen in adverts from the heyday of ocean cruises. It’s all rendered in clean smooth lines, with a single flat turquoise adding bold shapes and shadows that complement rather than follow the line-work. Logos and liveries abound, making a feature of Hughes renowned typographic skills, and adding to the believability of the world.

Dare would take it further, but this is an enjoyable if quick read. It came in a stylish hardback that’s long out of print and sought after. It might be worth the premium if you like fine books, otherwise it’s collected with Dare and more in Yesterday’s Tomorrows.