Review by Frank Plowright

Hergé‘s third Tintin adventure begins in Chicago with a fearful Al Capone instructing his henchmen to deal with the “world reporter number one”.

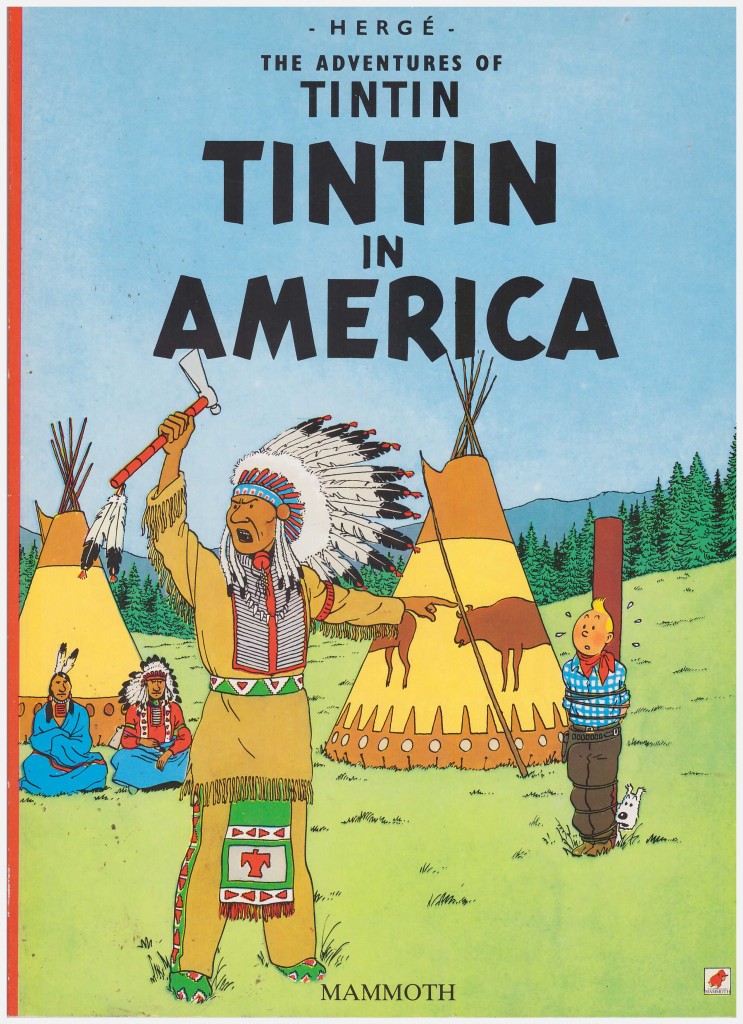

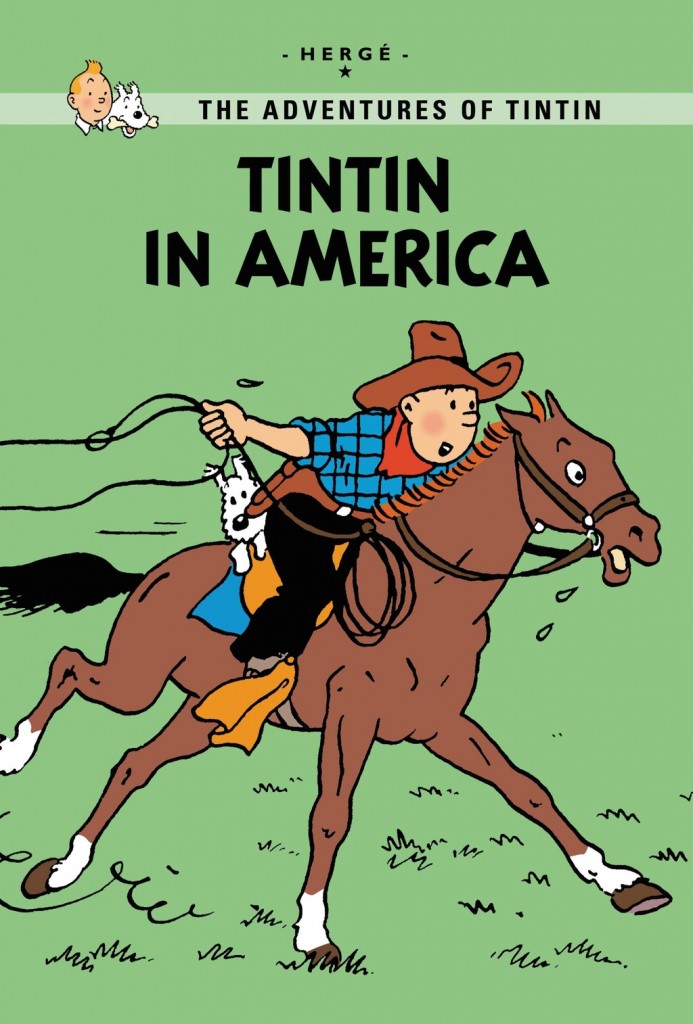

While a distinct progression from Tintin in the Congo, there’s a tendency to dismiss Tintin in America as lacking sophistication on the basis of what would follow, and while that’s not entirely unjustified, perhaps a fairer comparison might be with near contemporary work produced by others. The art alone ranks it ahead of well over 95% of what was published during the first decade of comics in the USA, and it pre-dates Superman’s début by six years. Yes, the now familiar version was re-drawn for colour in 1945, but as the facsimile edition of the original shows, the fundamentals were present in the original. Spectacular set pieces such as Tintin working his way from one window to that of an adjacent room outside a skyscraper or the final parade (constructed in reality to publicise the book) were already in place. Hergé‘s cartooning is already clear, expressive and a masterclass in storytelling.

Alas, the plot isn’t. It’s essentially one long chase scene, punctuated by incredible traps and even more incredible escapes, perhaps influenced by the adventure film reels of the day. Along the way Hergé throws in every American stereotype of the era. His depiction of native Americans draws increasing comment as racist, but his research was meticulous and his portrayal largely sympathetic.

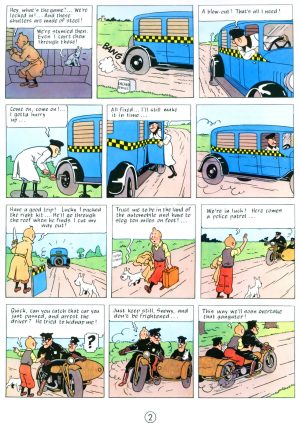

The precise plotting that would come to characterise Tintin hasn’t quite fallen into place here. In the opening pages there’s a gag about Tintin escaping from a sealed cab, but for it to work you have to believe firstly that Tintin happened to have a saw in his luggage, and secondly that his captor, then changing a tyre, wouldn’t hear Tintin sawing through the door. Other elements, deliberately exaggerated, still work, such as the construction of an entire city overnight following the unscrupulous eviction of the native Americans. It was requested Hergé remove this scene for publication in more conservative territories, but he always refused.

In the end, while acknowledging the progress, it has to be admitted that plotting on the wing pushes this down the rankings of Tintin material. Had Hergé not rapidly improved, on it’s own merits it would probably be long forgotten now. Next up was Cigars of the Pharaoh.