Review by Frank Plowright

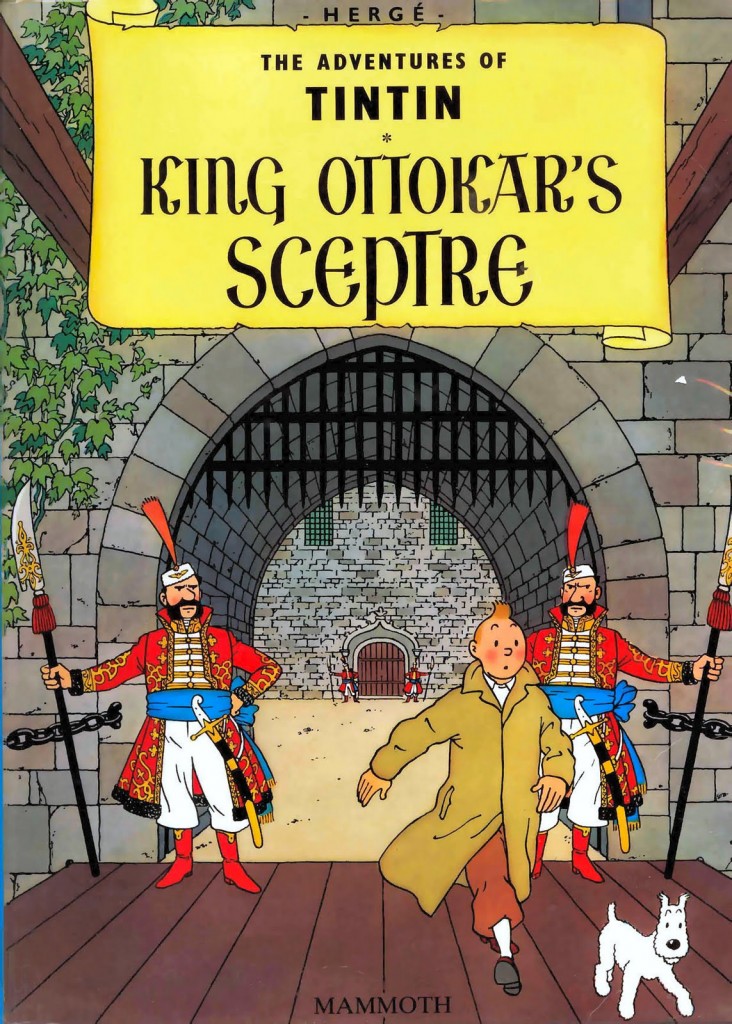

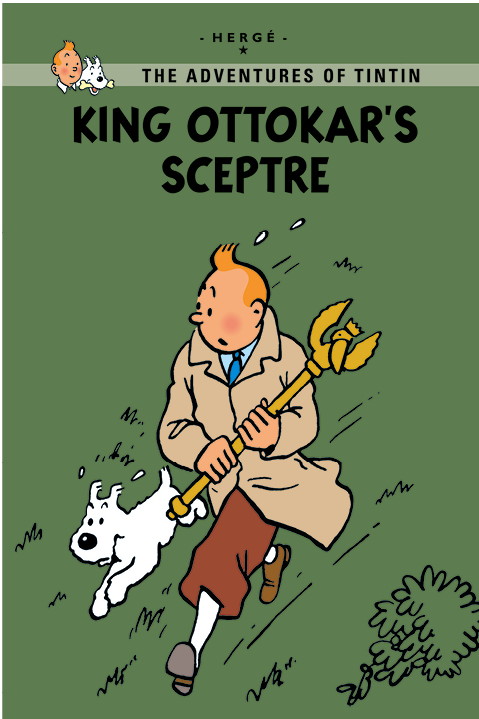

Over seven stories Tintin had become ever more adept at sniffing out adventure, and this one begins with a package left on a park bench that he returns to a sigillographist, an expert in seals (of the wax stamp variety). Professor Alembick announces his forthcoming visit to Syldavia to verify a seal, but mysterious events surround him, and after a primary investigation Tintin is warned to mind his own business. Instead he wangles a trip to Syldavia as the professor’s assistant, overcoming considerable danger in his attempts to meet the King.

By this time Tintin is convinced there’s a plot to steal the ancient sceptre of King Ottokar. This object is bestowed with great ceremonial importance, as Syldavian legend has it that if the King is unable to protect the sceptre of King Ottokar then he is unworthy to rule. It must be displayed in public annually on St Vladimir’s Day.

When King Ottokar’s Sceptre was originally serialised in 1939 Germany had occupied Austria and Czechoslovakia, and most of Europe feared war. Hergé fed this into his story, which was eventually revealed to be about annexation. Syldavia and neighbouring Borduria are noted as Balkan states, but Bordurian officers are clearly modelled on the German SS, and naming a Bordurian leader Müsstler is hardly subtle.

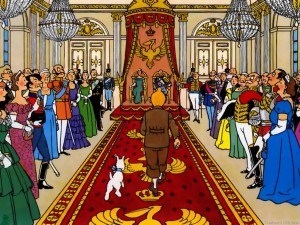

There are bold experimental storytelling elements here. Needing to explain the importance of the sceptre, Hergé conceived the idea of a faux tourist brochure as part of the story. Using typeset text and accompanying illustration, he was able to impart his history and customs of Syldavia in compressed fashion. He does so playing with the presentations of the eras represented, and in the now familiar colour re-working of the story then studio assistant Edgar Jacobs supplied a fine 15th century battle illustration. Jacobs also put considerable effort into adorning what had been plain art with decoration more befitting a European palace and Balkan settings.

Beyond the political implications this is another leap forward for Tintin. Comedy relief detectives Thompson and Thomson drop the idea of Tintin being their immediate suspect when they arrive at a crime scene, and now trust him as the paragon of virtue that he is, and Bianca Castafiore makes her début. The only woman seen semi-regularly in the Tintin canon is almost a force of nature, a diva expecting attention and privilege whose strength of personality enforces her will on others. Hergé treads a fine line, but Castafiore represents his ridicule of opera, not of women.

King Ottokar’s Sceptre is a deftly-plotted, exquisitely drawn adventure story and vies with The Blue Lotus for the best of Hergé’s pre-World War II output. The original French collection was as a black and white book, and an English language facsimile edition is now available. This was also the first Tintin story to be seen in Britain, when it began serialisation in The Eagle in 1951.