Review by G. Forrest

Spoilers in review

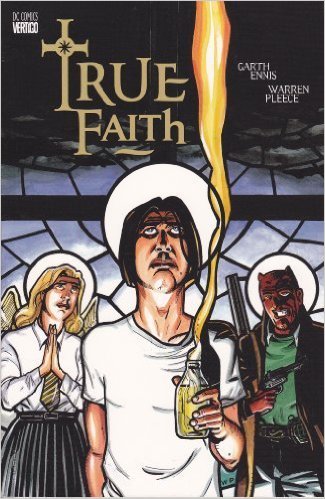

True Faith was the second published work of then fledgling writer, Garth Ennis. Ennis’ subsequent rise to prominence in the comics’ world is well documented. From the satirical decadence of tales such as Preacher and to the poignant hymns to heroism that made up his War Story one-shots, the Northern Irishman has sold many books, acquired an army of loyal fans and left a sizeable boot-print on the medium. There is always a fascination in revisiting and retreading at a writer’s first steps, those early, tentative exercises in finding a voice and a style. True Faith contains many of the ingredients that would become familiar to Ennis’ more (and sometimes less) sophisticated writing, from the skewering of religion to the satirising of the wanton hypocrisies of those in authority. Much of the formula that would shape the body of his work is evident is this early curio.

The story unfolds in late 1980s London, an era overshadowed and haunted by the iniquities and social disharmonies wrought by a grocer’s daughter. In this bleak landscape we find a pair of troubled souls. The first is Terry Adair, a man of faith who suffers a terrible and traumatising tragedy. This puts him on a volatile collision course, a la Preacher, with an uncaring God who Adair swears to murder. In the story, Adair sees the world as a toilet and God a blockage in the u-bend that must be disposed of. His unholy mission leads him to cross paths with a cynical, irreligious teenager, Nigel Gibson, and the unlikely pairing form an uncomfortable and disturbing kinship in their war against religion. The initial stages of the story work well and showcases Ennis’ early talents for characterisation but the direction of the tale itself becomes less sure footed when the writer introduces an anti-religious paramilitary force also bent on executing God, allowing a little too much contrivance to unsettle the narrative. Elements introduced in True Faith are ones that Ennis would revisit throughout his career with more assured and bravura storytelling.

True Faith’s interest lies in letting Ennis fans trace back the ancestral DNA of much of the gifted writer’s later work. It is a modest, flawed but ambitious book, ably supported by Warren Pleece’s purposely ugly but expressive art. Just as Nigel Gibson begins his coming of age arc, so too does Ennis. While True Faith is unlikely to regarded as more than a footnote in Ennis’ career, it is an experimental, but minor tale that foreshadows the greater legacy that Ennis will leave behind in the hearts of lovers of graphic storytelling.