Review by Ian Keogh

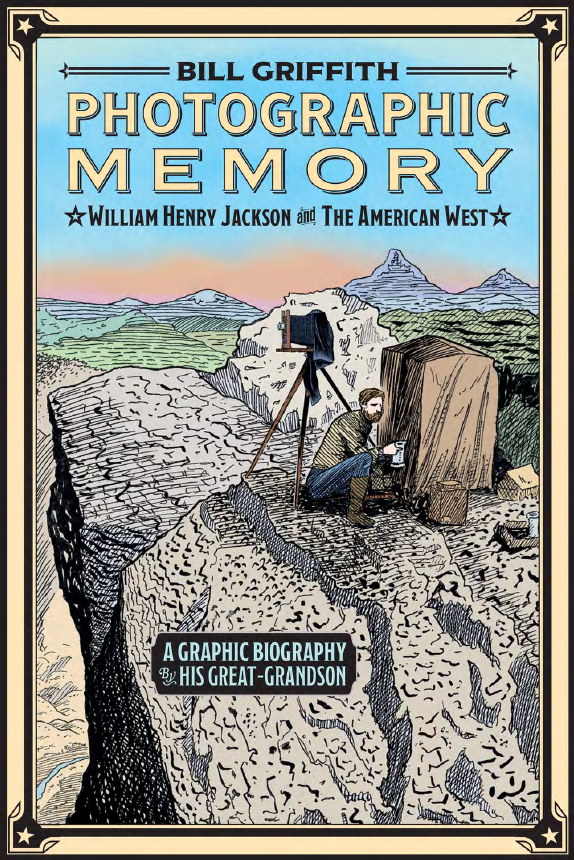

When a young child William Henry Jackson Griffith was told his names originated from his great-grandfather William Henry Jackson, a photographic pioneer who died two years before Griffith was born. As a youngster he’s pleased to be the only kid in school with four names, but as time passes he learns more, and now aged eighty Griffith has produced a graphic novel biography of his ancestor.

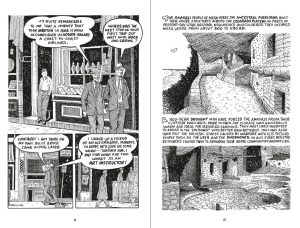

Photographic Memory isn’t a straightforward biography, being told primarily as Jackson’s recollections in old age, yet also including Griffith’s own memories of incidents with a bearing on Jackson’s legacy. Much of this was as related to Jackson’s friend Elwood P. Bonney from 1933, and Bonney later published a book of his memories about Jackson based on his diaries. Griffith draws extensively on this as his intention is to deliver as full a picture as possible of his great-grandfather’s life, but although the illustration is refined, two elderly gentlemen eating in diners and making jokes about Gone With the Wind is hardly the stuff of legend. What is conveyed via Bonney’s recollections is Jackson being down to Earth and little concerned in old age with the status and reputation important to him when younger.

Likewise, Jackson’s younger years reflect the era without being compelling until a moment of impetuosity ends his East Coast life and begins his journey westward, which is when Photographic Memory springs into life. We’re not long into that before Griffith breaks in to explain inherited guilt concerning terminology Jackson used about indigenous Americans and how he commodified them in photographs. A dozen pages of hand-wringing including testimonies from 19th century Native Americans would have been better placed as an addendum. Oddly, what would now be seen as Jackson neglecting his family is only briefly aired.

An accomplished artist, it’s nonetheless a challenge for Griffith to supply the majesty of the scenery as viewed by Jackson, and perhaps from respect he rarely attempts to reproduce a photograph exactly. Some of Jackson’ pictures are presented in the back and some of his drawings make the body of the book. When it comes to urban environments of the past, though, Griffith excels, supplying neat small drawings of so many locations, every single one of them something to pause and look at before moving onward.

By not just concentrating on the successful career highlights, Griffith underlines that people seen as successful today experienced periods of hardship and struggle. Although Jackson in his nineties had a reputation and a name, he still felt it necessary to work to supplement his pension. That may have been partially an excuse as he’s portrayed as loving to draw the past as much as he talked about it. His photography wasn’t confined to the USA, and one of Photographic Memory’s most enticing sequences is a global trip taken in the late 1800s in the company of a man who proves a charlatan.

What begins in relatively tame fashion eventually becomes an exhilarating journey of highs and lows. Hand-wringing apart, it’s enlivened by Griffith’s intrusions, with an imagined ferry conversation charming, and his whimsical epilogue funny. For the reader with an enquiring mind much is mentioned in passing meriting further investigation, Sally Rand’s Nude Ranch for one.

Exhaustive, densely compiled and illuminating, Photographic Memory is a testament to Jackson’s spirit of adventure and to Griffth emulating his ancestor by still producing work of quality at an advanced age.