Review by Ian Keogh

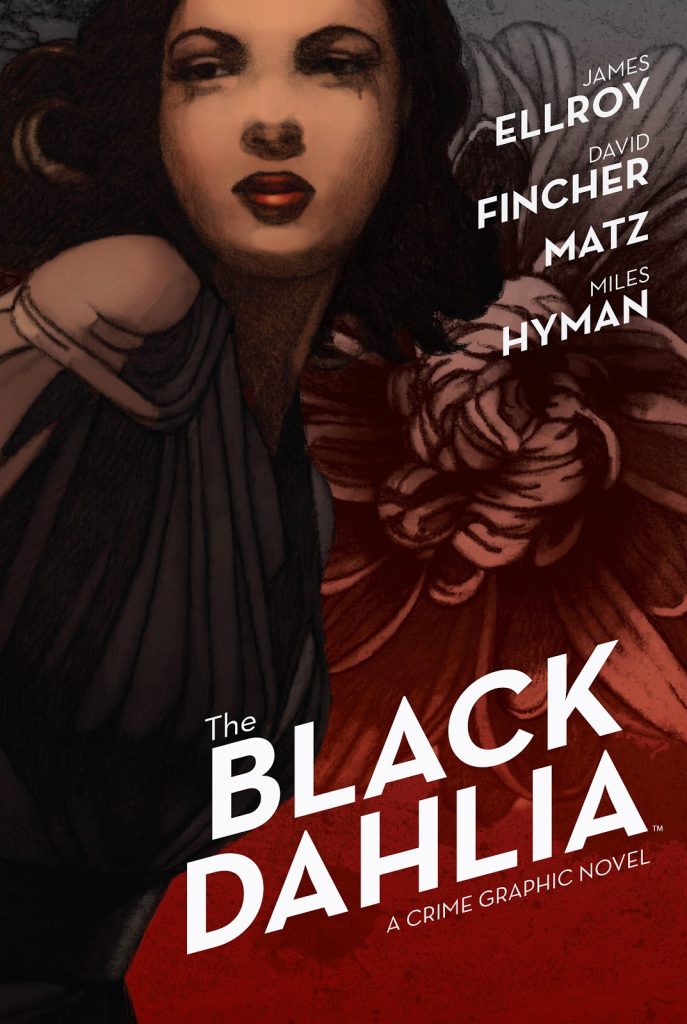

The case of the Black Dahlia is a notorious unsolved murder from 1947, a year before future acclaimed novelist and fellow Los Angeles resident James Ellroy was born. Tragically, Ellroy’s mother was raped and murdered when he was ten, the circumstances leading him to identify with the similar death of Elizabeth Short, and in 1987 he published crime novel The Black Dahlia. The graphic novel is an adaptation by French writer Matz (Alexis Nolent) in collaboration with film director David Fincher and Myles Hyman, who combines his fine art career with the occasional graphic novel.

Ellroy’s novel incorporates the facts of Short’s death and the subsequent investigation, but greater prominence is given to the surrounding interpretation of fictional investigating detectives Lee Blanchard and Bucky Bleichert, both former boxers. An immediate shock is the unsparing dialogue when it comes to the racism of the times, while Bleichert’s eventual promotion to the partnership involves chicanery. It establishes early the type of men the LAPD employed at the time, their attitudes to life, and how that impacts on police work. It’s unflinching and appalling, ramped up to levels intended to shock even a readership familiar with corrupt cops.

Matz and Fincher attempt to retain much of Bleichert’s first person narrative from the novel, frequently using captions in preference to dialogue, which in turn feeds into the painterly approach taken by Hyman. Every panel is an individual composition with the focus on the people, but within carefully constructed environments. It’s a surprise to see this extended to a lingering examination of Short’s naked and mutilated corpse when the case breaks open around a third of the way through. Hyman’s extremely good with static images, but lacks the vitality required whenever there’s motion. Due to The Black Dahlia’s procedural approach it doesn’t impact greatly, but there is a fourth chapter scene where movement would be required and so it isn’t as effective as it might be. Another minor irritation is several typos in the lettering, one of them in an important scene at the end.

As the narrative opens up, similarities become apparent with Blanchard’s motivations mirroring the young Ellroy’s obsession with the case, and the relentless downbeat monotony is seeded with scenes calculated to offer different circumstances, but which prove equally bleak. The interlude of a hostile family dinner proves as uncomfortable as events surrounding the investigation. That becomes a toxic stew as the complications of private lives spill into work, and Blanchard has the extra problem of a gangster just released from jail who’s threatened to kill him.

While the characters and the investigation can make or break a crime story, both can be fudged to a degree as long as the mystery is captivating and the resolution pays off. The Black Dahlia does as the secrets come tumbling out in the final two chapters. They’re humdingers explaining earlier seemingly random events as planned. accompanied by heavy doses of psychological disturbance. Someone once noted there are no happy endings in the real Hollywood, and there certainly aren’t here. Ellroy supplies a resolution that never happened in actuality, although cleverly ensures it also explains why the case remains open.

The final chapters are heavy on exposition, but drip with emotional resonance, sealing a great adaptation.