Review by Ian Keogh

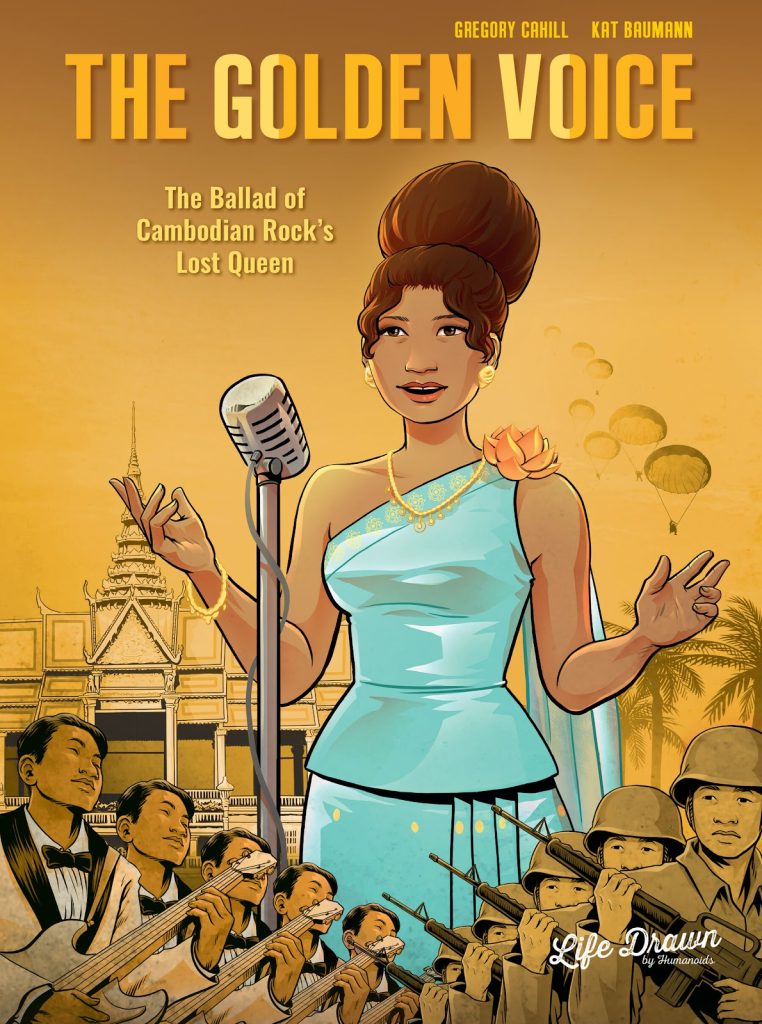

The South-East Asian country of Cambodia has a unfortunate history since the French invaded in 1863, but the most brutal and repressive period was just over a century later. Gregory Cahill and Kat Baumann explore the beginnings of the Khmer Rouge era via the musicians of the time, particularly Ros Seray Sothea.

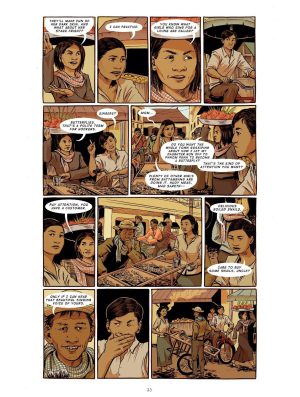

It takes a time for the political background to manifest and before then we see the rise of Sothea from selling snails in the market to radio sensation. The radio system in Cambodia was set up by the Prince, and involved employing the singers rather than playing records, which led to an opportunity when Sothea won a local talent show. She’s immediately sucked into a world of Cambodian celebrities, earning the disapproval of her mother and an exceptionally jealous husband, while her talent seduces a nation.

In terms of actual writing Cahill is of the less is more school, frequently letting Baumann’s wordless panels supply the environment, mood or reaction. She’s very good at this, employing a clear style showing what’s being felt at all times, and defining locations well.

There’s considerable effort made to ensure The Golden Voice is a greater immersive experience than is usual for graphic novels. At various points little play icons correspond to a curated playlist accessible via QR code, and word balloons are coloured according to the language spoken. This has deeper relevance as the story progresses and the conversation isn’t exclusively khmer. When the Vietnamese War spills into Cambodia the USA avidly supports a new regime, and their plotting and enthusiasm features. As has so often been the case, in the name of preventing one regime via donating weapons, “advisors” and information, the US create something infinitely worse, later acknowledged by one of Cahill’s characters.

Sothea only wants to sing, yet increasingly finds both her life and career compromised by the political turmoil, and then far worse. It’s often the case that hardship shapes art, but the deterioration of Cambodia elevates that maxim beyond the norm, and Sothea being a woman makes her less able to resist exploitation and abuse. Cahill efficiently relates the disaster of a career subverted and derailed by political ideology from the beginning, with Baumann’s attractive art mitigating some appalling events.

A smoother narrative accounting required compromises, and for the sake of accuracy Cahill follows Sothea’s story with notes indicating where fictionalised moments have been used. If anything, tragically, in some instances the reality is worse than the fiction.