Review by Frank Plowright

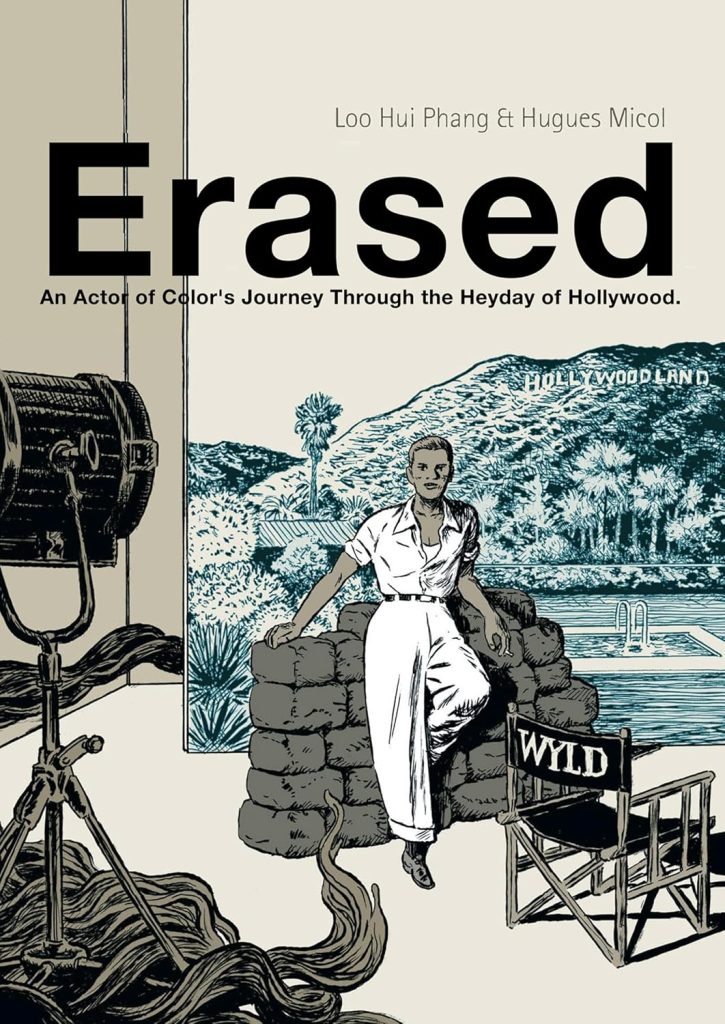

Erased is a viable idea that frustratingly fails to achieve fruition. Maximus Wyld is a fictional historical implant spanning Hollywood’s golden era from the 1930s to the 1950s, a man of mixed race whose features are nebulous enough to pass as a young Tibetan in his first film, yet take other minority roles thereafter. He’s smart and attractive, so in demand, but never for the leading roles that would showcase his natural talent.

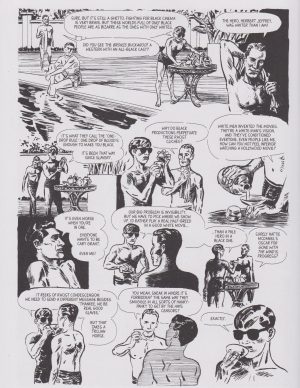

Zelig must have been an inspiration for Loo Hui Phang as Wyld mixes with the famous and notorious, his good looks and intelligence opening doors, and Wyld taking advantage of what’s on offer. Kenneth Anger’s two Hollywood Babylon books top a list of references, presumably avoiding any accusations of slander on Phang’s part as Wyld beds one famous actress after another. As he’s on film sets he talks to others from ethnic minorities he acts alongside, hearing their views on the characters they play, and questioning the roles he’s given. Between those segments Phang runs through Hollywood’s shameful history of racism and ridicule, and also reveals the compromises made by the bigger stars of the 1940s and 1950s.

It’s a heady brew with worthwhile points to make, and a clever insertion of Wyld into Hollywood history, but too many blatantly scripted conversations along the same lines transform explanations into lectures no matter how relevant they are. And there’s a further drawback…

According to the informative Bdgest site Hugues Micol’s career is entirely 21st century, yet his art resembles something created sixty years earlier. It’s overworked with too many lines and too much shading, and even so people are too often poorly drawn, presented in impressionistic studies, with likenesses of the famous rarely achieved. Nor does Micol supply the grandeur to symbolic full page illustrations of Wyld swamped by his inner doubts.

As Erased continues, so do the ideological discussions, drama all-but absented in order to present them on one film set after another. Famed film directors and movie stars are supplied in cameos to deliver homilies and platitudes, and Wyld constantly questions his purpose as Phang moves from racism to witch hunts. The occasional salacious revelation, such as a film studio hiring a brothel populated by film star lookalikes, is a rare departure from being swamped by dialogue deconstructing film projects.

Perhaps the revelations about Hollywood’s tawdry past might have more appeal to anyone reading them for the first time, but neither creator is able to bring out the worth of the story. By the time we reach Wyld’s Hollywood demise via anti-Communist witch hunts he’s so long been a mouthpiece for lectures, that there’s no character left to pity.