Review by Frank Plowright

When Marietta and Chuck decide to have a baby together, all goes well until a difficult final two weeks of pregnancy, resulting in constant pain. The birth is also difficult, and Marietta isn’t supplied with the most sympathetic of attendants. The pain remains after birth, and she finds herself lacking an instant maternal bond with her daughter.

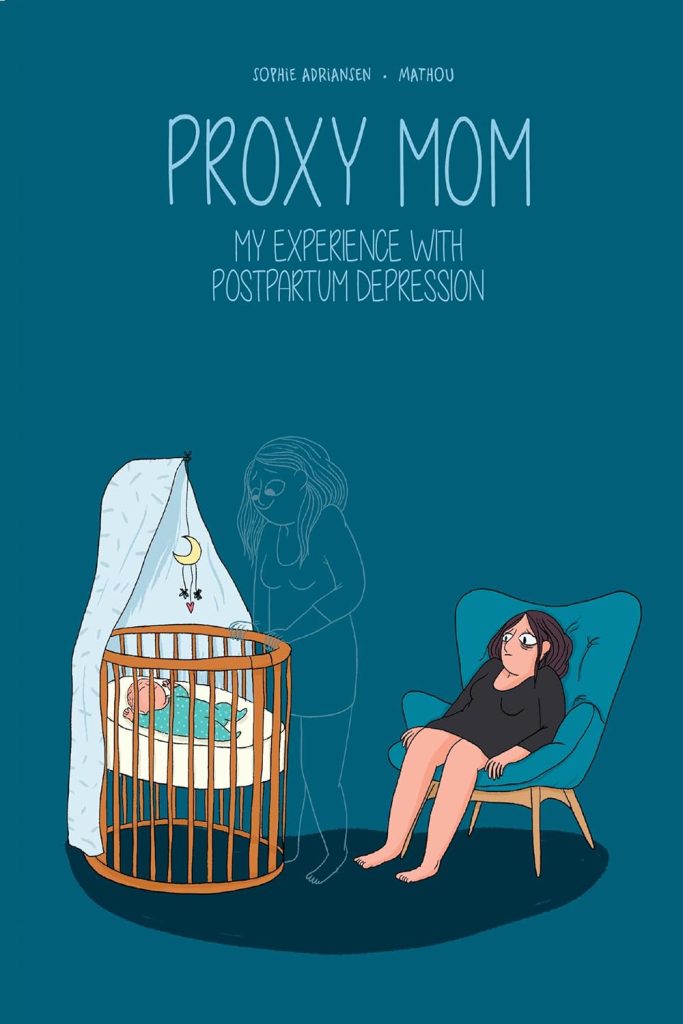

Despite illness and medical conditions being an ever increasing subject for graphic novels, NBM’s accompanying publicity notes Proxy Mom as being the first graphic novel to address the depression many new mothers experience after giving birth. The biographical information draws parallels between writer Sophie Adriansen and Mathou (Mathilde Virfollet), and reveals that despite Proxy Mum being fictional, Adriansen herself suffered from post-natal depression. Before Proxy Mom it was also the central theme of a novel she’d written in 2017.

The title derives from Marietta fantasising about an invisible proxy mother who’d carry out all the tasks necessary for the baby’s wellbeing. She’s rapidly discovered that far from the arrival being the greatest day of her life, if she’s truthful, she doesn’t actually want the baby. It’s such an unconventional and alien thought that guilt is the immediate accompaniment.

Until relatively recently it was also an undiagnosed condition, but until the final pages Adriansen steers clear of background information unless personally affecting Marietta. Hormonal imbalance leading to depression is mentioned in passing, but seemingly not taken in. What fictionalising allows, though, is a more personal experience, as Marietta wrestles with the anguish of conflicting feelings, sure that if she confesses the truth it will alienate Chuck, yet not connecting the hormonal imbalance with what seems incredibly selfish feelings. It’s some time before medical recognition of how Marietta is feeling.

Passing on information is key, so there are no distracting flourishes to Mathou’s plain cartooning. The technique is a very expressive conveying of Marietta’s multiple emotions, beginning with the joy of anticipation, and sinking into doubt and uncertainty.

There may be a feeling that there’s too little medical advice, but as with so much about people, there is no universal solution. Marietta is shown visiting a therapist, and in her case post-natal depression evaporates after five months, which isn’t the case for everyone. Adriansen bemoans that in the 21st century a condition affecting one in seven new mothers, or 36 mothers per minute in the USA, still isn’t adequately addressed. Social and to some extent medical expectation is that mothers just get on with it, which only increases anxiety, and not enough support is available.

That’s presumably not going to change rapidly, but in charting Marietta’s feelings Adriansen and Mathou can at least supply some understanding that post-natal depression isn’t individual selfishness.