Review by Ian Keogh

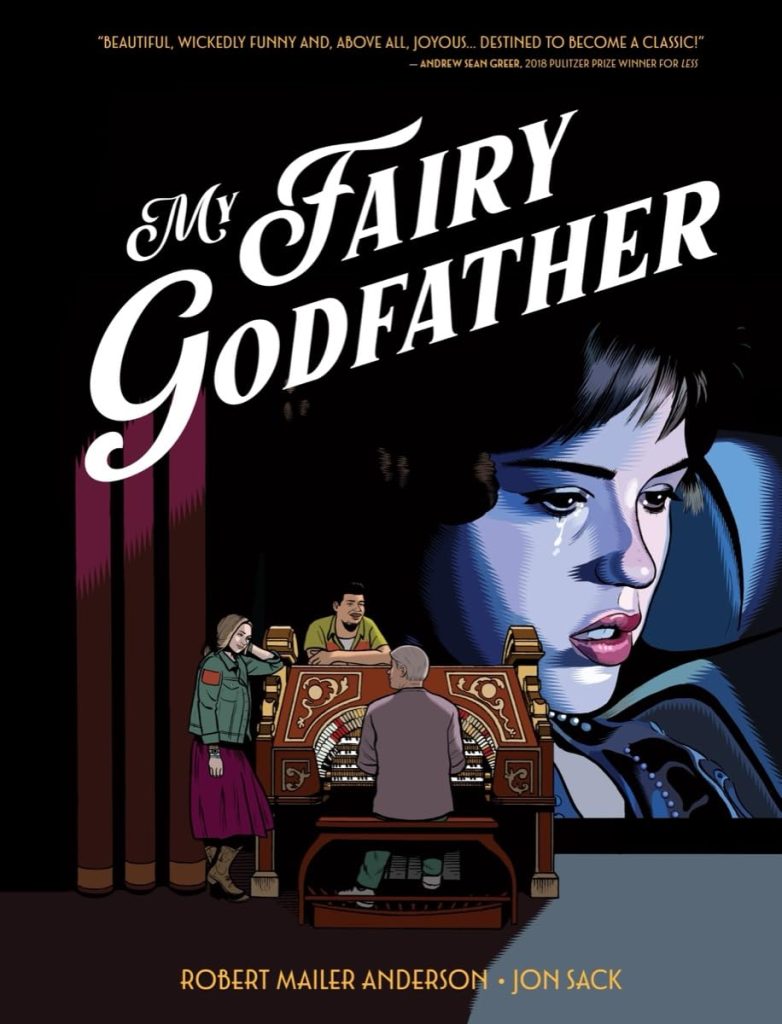

When her parents die their wish is that their teenage daughter Billie is raised by their college friend Adam, a gay film enthusiast who runs a cinema in Kansas with his partner Steven, although they don’t live together. Billie’s Aunt and Uncle don’t agree with the decision, but respect it, and My Fairy Godfather opens with them dropping her off with Adam.

What follows is an observational and conversational drama about how to cope with something you’ve never planned for, and what it means to be yourself where opposite views are firmly entrenched in society. The choice of Liberal, Kansas as the location is a sly joke for what’s portrayed as a largely conservative town where having opinions and styles outwith the hive mind is cause for derision and condescension. Should Adam and Billie take a stand for what they believe in, or try to get by quietly?

In places over the first third of My Fairy Godfather Robert Mailer Anderson has the cast explain themselves extremely earnestly, feeding into an expressed view of honesty and trust being foundations of any relationship. Elsewhere he manages to nail understanding and sympathy in a pithy phrase, many originating with Steven. Anderson is a leisurely storyteller, gradually inflating pressures and conflict to a crisis point, by which time you’ll be surprised how well you’ve come to know the cast. Despite her grief Billie’s able to avoid responding to ignorant, and wrong, assumptions, and while Adam’s well intentioned he’s not inclined to rock the boat in a community where he’s spent his life and runs his business. The only character who doesn’t really transmit is the brother of Billie’s best friend, contriving wackiness rather than the intended free spirit.

Artist Jon Sack is very influenced by the cartoon naturalism of Jaime Hernandez, down to the vibrant flat colour, but will then surprise by dropping a portrait that could be by Dan Clowes, with whom another connection is a preference to have people standing rather than moving. Where Sack definitively departs from Hernandez is via using multiple small, precise panels on a page, switching from person to person effectively and supplying fully realised backgrounds. Page after page is attractive and eye-catching.

The ending is a little too easy and sentimental, but also a crowd pleaser, and having followed the lives of decent people for so long, it’s what you’ll want from a fine and well observed drama.