Review by Frank Plowright

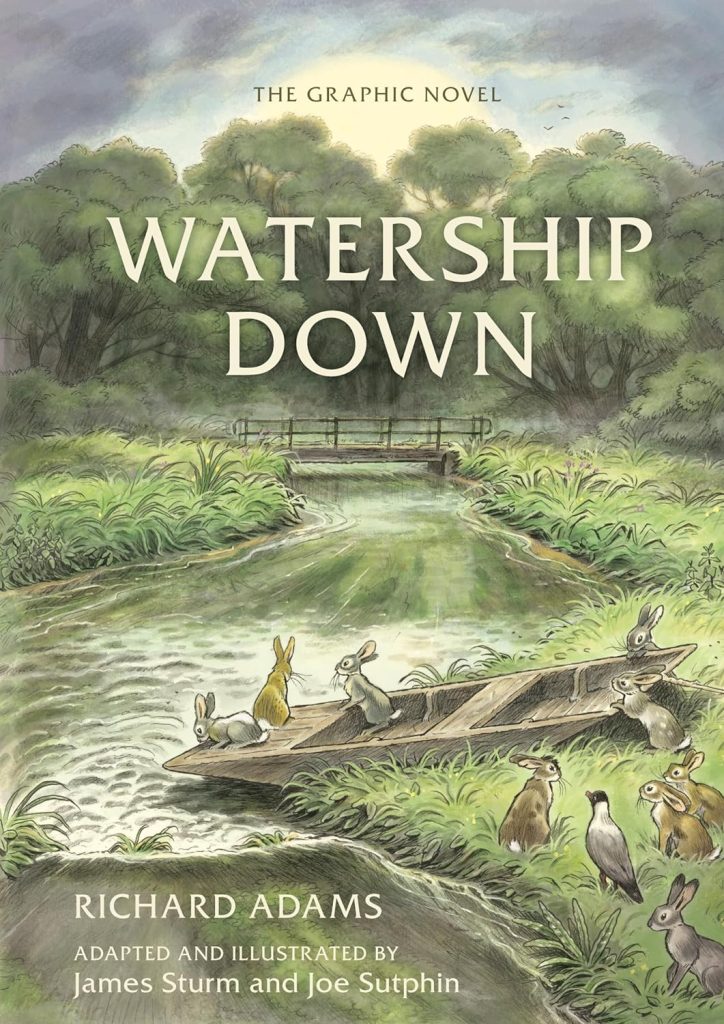

Given its status as a perennial family favourite and the country setting inviting visions of natural beauty, it’s a surprise Watership Down hasn’t been adapted as a graphic novel before now.

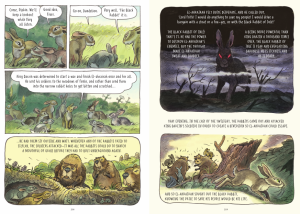

Richard Adams originally anthropomorphised the society of rabbits in country fields, their customs, myths and hierarchy to entertain his daughters during car trips. When encouraged to solidify the stories he drew on his World War II military experiences to construct a threatening journey. As it’s been so long since the original publication and resulting film, it’s worth emphasising that despite the cute illustration, Adams was no sentimentalist, and his rabbits face the same dangers as rabbits in the wild. In places Watership Down is violent and upsetting.

The young rabbit Fiver has a form of precognition and senses a forthcoming threat requiring the entire community to move their home. Readers are shown a notice mentioning planned redevelopment of the land, yet their leader remains unconvinced on such slim evidence, and eventually only a small group of rabbits undertake a journey. They have different names for assorted creatures that mean them no harm, but crows, dogs and weasels are referred to by the names familiar to readers.

Watership Down is Joe Sutphin’s first graphic novel, but his speciality is illustrating children’s books involving animals, and his lively illustrations tell the story effectively, working from James Sturm’s breakdowns. A minor complaint is that with such a large cast of rabbits, it’s sometimes difficult to distinguish one from another without the dialogue, but Sutphin manages to draw a rabbit looking sly or predatory, which is no mean feat. His illustrations of the countryside, rooted in the 1960s, are panels of beauty, but unlike the 1970s film there’s greater concentration on danger than the appeal of nature, making this adaptation more faithful to the novel.

While not everyone trusts Fiver’s premonitions they’re consistently correct, despite some at first not seeming that way, and this is reinforced with the later appearance of rabbits who originally refused to believe Fiver’s warning of danger. While that element is fanciful, realities of life for rabbits are the backbone, Adams including items such as a group of male rabbits aware they’ll need to add females if their new warren is to have any longevity.

Sturm chooses not to include Adams’ spiritual epilogue, but this is otherwise a successfully faithful and attractive interpretation designed to introduce a beloved story to a new generation.