Review by Frank Plowright

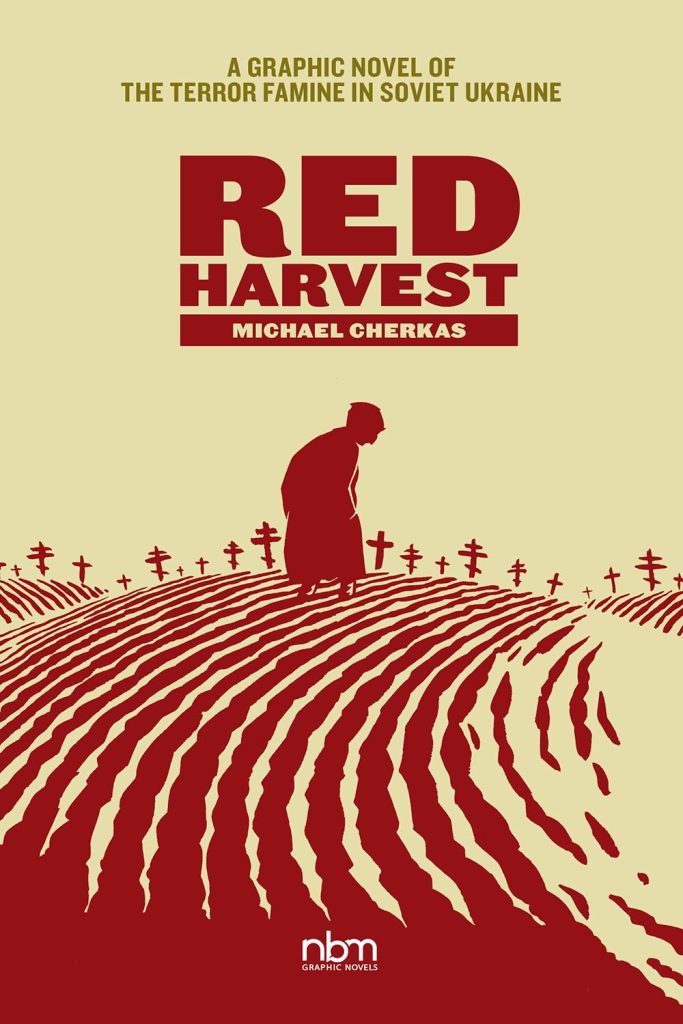

In his introduction Michael Cherkas notes being intimidated by the creation of Red Harvest, a combination of Ukrainian heritage and human compassion wanting to ensure the appropriate weight is given to a tragedy. It is, harrowingly.

Translated from Ukrainian, the term ‘holodomor’ can mean either death by hunger or killing by starvation, and it’s applied to what occurred in Ukraine in the early 1930s, then controlled by the Soviet Union. It’s annually mourned to this day. Cherkas details events via Mykola Kovalenko, living in Canada in his eighties, and appalled that his young grandson doesn’t finish meals. It’s a common enough complaint of grandparents who’ve lived through a war and hardship, but Kovalenko has reasons predating World War II.

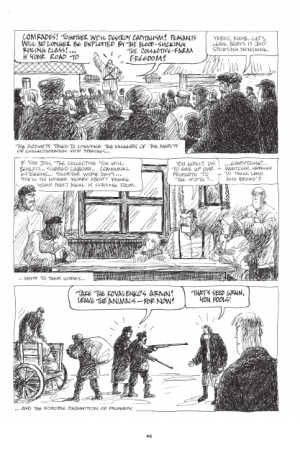

In 1928 he was a child on the family farm in Zelenyi Hai, and at first life seems relatively idyllic, although Cherkas shows with small touches how Soviet strictures are beginning to sneak into everyday events. Ukraine has long been the region’s primary grain producer, and Soviet leader Josef Stalin’s plan is for the area to become more efficient by merging small farms into larger collectives, with mechanisation replacing slower harvesting methods. While that might make sense in principle, nothing was voluntary and dogmatic Communist party members were placed in charge rather than the experienced farmers. Within a year former friends are at each other’s throats and a tragedy has begun.

Personalising events might mean putting words into people’s mouths, but Cherkas showing a family torn apart makes for a far stronger statement than just the bare facts. He portrays them and their sparse surroundings using a simple pencil style, noted in his introduction as evoking the idea of quickly drawn forbidden sketches smuggled from the area. It’s entirely appropriate.

Cherkas details a double tragedy. Farmer after farmer is exiled or arrested and transported to Soviet labour camps, leaving few people to run a massive farm set impossible targets, while what is produced is shipped out to be sold to fill the Soviet coffers. Those who’re exiled starve and those who remain starve, all in the name of ideology. It’s monumental stupidity counted in human lives, and an emotionally draining and depressing narrative, which is, of course, the intention. Every time it’s assumed the inhumanity has reached the pit bottom, Cherkas reveals there’s further down to burrow. There’s an interesting parallel to the 2023 UK government using old Soviet techniques by legislating Rwanda a safe country for everyone when it’s patently not. In 1932 the Soviet authorities declared there was no famine in Ukraine, and therefore there wasn’t despite the widespread starvation.

While the people are fictional, this shouldn’t detract from Cherkas using them as vessels for genuine experiences. It’s mentioned when he’s introduced that Kovalenko was the only family member to survive and in detailing the gradual dissolution of the family Red Harvest is a horrific exploration of a period little known in English speaking societies. It’s difficult reading, and it must have been even more difficult for Cherkas to create, living with the details for so long. It’s also an poignant, tragic and a brilliant example of what comics can be.