Review by Karl Verhoven

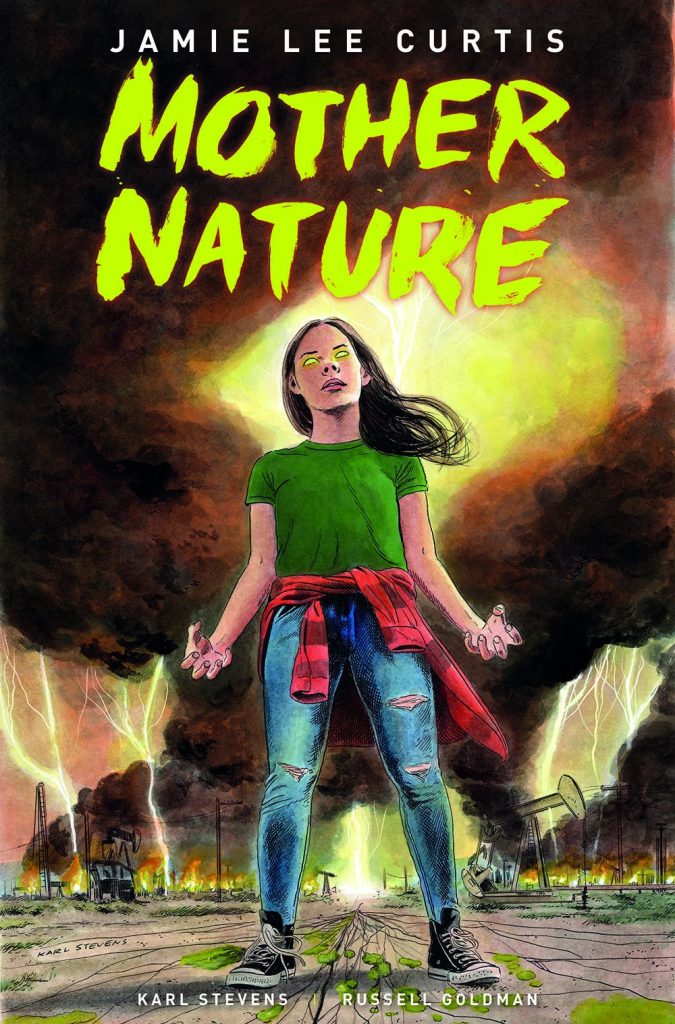

Mother Nature is an unpredictable graphic novel, rooted for a considerable time in the depressing reality of rich companies being able to run roughshod over small rural communities, before taking a surreal turn into wish-fulfilment fantasy enabled by the supernatural.

Jamie Lee Curtis apparently conceived the idea of a film about nature fighting back against being despoiled when new to the film industry, but the actual film script adapted here is of a far more recent vintage, a collaboration with Russell Goldman for her production company. It was then broken down as a graphic novel by artist Karl Stevens. That’s instructive as it highlights the difference between the needs of a screenplay and the different needs of a graphic novel. With movement it’s not necessary the cast connect with the audience instantly as there’s enough else to occupy the eye, but static storytelling requires greater explanation. It’s a good way through Mother Nature before the connections between featured people are clarified, and it discourages emotional investment in what are ordinary circumstances. That investment arrives around a third of the way through via a supremely awkward party scene explaining a lot.

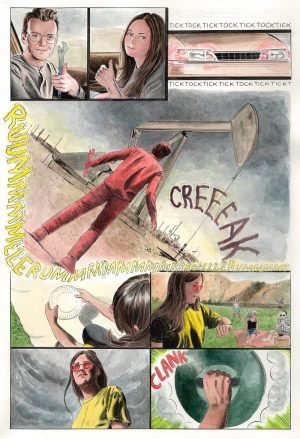

Before then the relationship between Nova and her mother is clearly defined. Nova still resents her father’s death and has a certainty about where the blame lies. She’s committed to fight injustice no matter the personal cost. Conversely, her mother has decided less stress in her life is the preferable option. “Where do you think we’d be without their money?” she asks, almost rhetorically. Emotional resonance is important and Stevens brings this out, and also identifies the broad open spaces cultivating the sense of isolation. His watercolouring is inconsistent, in some places creating the ideal mood and in others clashing shades draw attention rather than keeping the story flowing.

When the inexplicable begins to occur some Catch Creek residents accept it better than others. To Kai, Nova’s mother it’s the manifestation of old Native American legends about malevolent spirits, and it’s with their introduction Mother Nature switches into cinematic horror where the mystery becomes which of the cast will survive. That’s important because by then the bonding between various cast members has been well constructed, especially with reference to the past always informing the present.

Mystical fudging toward the end is supplied in quantity, returning to the barely credible melodramatic convenience that sets everything in motion, and beyond that Stevens doesn’t always convey exactly what’s happening well enough. The background message of the water company being ill-intentioned and uncaring is also all too conveniently twisted into the road to hell being paved with good intentions, and the urgency of the ending is something that would work more effectively on screen.

Overall, that’s the feeling about Mother Nature in general. As a graphic novel it’s readable, but not greatly memorable, but with the nuance of performance added it could be.