Review by Roy Boyd

Asterix and the Great Divide is the 25th Asterix book, but more notably the first both written and illustrated by Albert Uderzo, following the death of his long-time collaborator, writer René Goscinny.

Uderzo and Goscinny explored the idea of internal conflict and political divisions within Asterix’s village in Asterix and Caesar’s Gift. However, the series had never shied away from recycling ideas, and it was a tradition Uderzo fully employed here, where he effectively reuses the set-up from Caesar’s Gift, but moves it to another village.

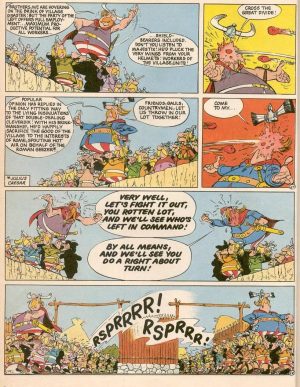

The village in question, led by Chiefs Cleverdix and Majestix, is literally split down the middle by a big ditch, a mocking reference to the Berlin Wall. Throw in a couple of star-crossed lovers, Histrionix and Melodrama, son and daughter of the respective chiefs (of course) and a manipulative and treacherous advisor with designs upon the beautiful young maiden and the chieftaincy of the entire village, and you have yourself a political drama with shades of Romeo and Juliet.

The machinations of Codfix (think Grima Wormtongue, King Theoden’s advisor from The Lord of the Rings, but fishier) brings the Romans into the picture, and Cleverdix, hearing of this, appeals to Chief Vitalstatistix, who quickly dispatches Asterix, Obelix and Getafix the druid to attempt to sort matters out. After all sorts of hi-jinks – kidnappings, fights at sea, magical transformations and fights galore – our heroes are able to bring matters to a conclusion that benefits everyone. Well, all the Gauls, the Romans don’t do so well out of the whole deal. And if you don’t know how things work out for the pirates, then you obviously haven’t been paying attention to the series so far.

The book’s title is fairly apt, as this adventure polarises fans. Those who felt the series had become lacklustre were pleased with the direction Uderzo took, while others thought he’d moved too far from the type of stories they’d grown used to. Goscinny’s absence is keenly felt, with some of the writing heavy handed, as Uderzo lacks his late creative partner’s facility with language. However, this is to be expected. Goscinny was masterful at writing this type of adventure, and it’s a bit much to expect Uderzo, who had been equally responsible for the huge success of the Asterix books, to be just as good, especially on his first solo effort. He never matched the creative heights the pair reached together, though he would produce another handful of solo titles, with varying degrees of success.

The artwork also deviates in style somewhat from what readers were used to. Uderzo is more realistic than usual in his depiction of some characters (like Histrionix), and less realistic than usual in his depiction of others, specifically Codfix, who is so unattractive, fangs and all, that one keeps expecting him to be revealed as a scout for an invasion of fish-people. In general, the artwork is polished, though not as detailed and slick as the earlier books.

As one would expect, Goscinny’s writing is sorely missed, but it’s not bad for a first solo outing, with Uderzo trying his best to fill a very large pair of shoes.