Review by Win Wiacek

The creative renaissance in comics during the 1980s resulted in some utterly wonderful standalone sagas that shone briefly and brightly within what was still a largely niche industry before passing from view. Sadly among them was Last of the Dragons, but perhaps Dover’s reissue of a collection out of print since the 1980s can rectify the situation.

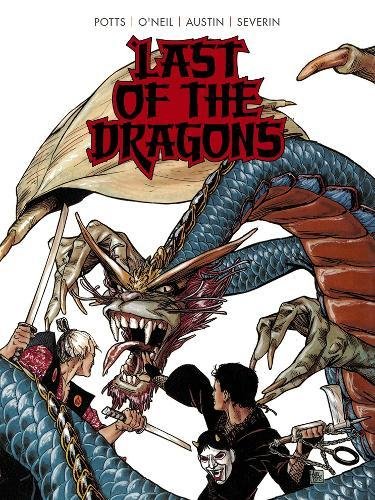

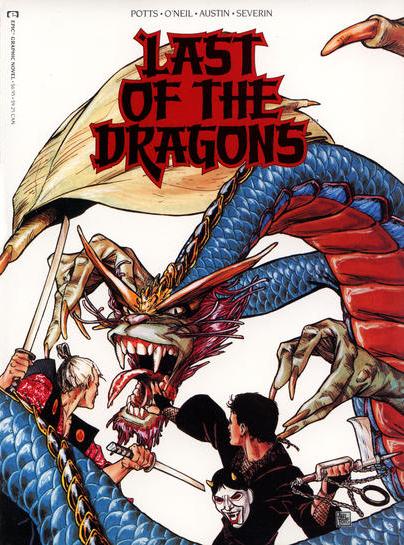

Conceived by then-newcomer Carl Potts, he plotted and pencilled the globe-trotting saga for Denny O’Neil to script, before inker Terry Austin and colourist Marie Severin finished the art. The Epic collection was issued in an expansively extravagant and oversized European album format: a square, high-gloss package delivering so much more bang-per-buck than a standard funnybook. Thankfully Dover’s edition retains those generous visual proportions.

It begins with ‘The Sundering’, opening in slowly-changing feudal Japan of the late 19th century where aged master swordsman Masanobu peacefully meditates in the wilderness. His Zen-like calm and solemn contemplation are callously shattered when a callow, arrogantly aggressive warrior attacks a beautiful dragon basking nearby in the sun. These magnificent reptiles are gentle, noble creatures but the foolish samurai is hungry for glory and soon wins a bloody trophy.

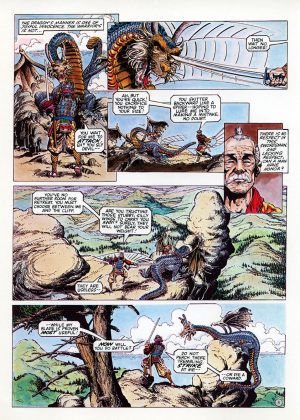

After the arrogant victor has left Masonobu meets Ho-Kan, a priestly caretaker of Dragons. The youth is overcome with horror and misery at the brutal sacrilege, but worse is to come. When the tearful cleric heads back to his temple home, he stumbles upon a corrupt faction of his brother-monks covertly conditioning young forest Wyrms; shockingly brutalising them to deny their true natures and kill on (human) command.

‘The Vision’ finds traumatised Ho-Kan returned to the temple too late. Ambitious, reactionary monk Shonin has has divined that the quiescent Dragons must be used to preserve Japan from outside influence – and especially the insidious changes threatened by the encroaching white man’s world. In fact he has already been training the creatures to be his shock-troops.

When the elders object, Shonin’s zealots slaughter the protesting monks before embarking for the barbarous wilds of America where they will breed and train an army of killer lizards under the very noses of the enemy. Ho-Kan is one of precious few of the pious to escape the butchery and vows to stop the madness somehow. In a meditative vision he sees Takashi: a mixed race boy whose Christian sailor father abandoned him. The juvenile outcast was eventually adopted and became a great fighter. Somehow he holds the key to defeating Shonin.

Japanese ninja comics and their trappings hadn’t been translated into English when Potts launched his series, providing an immediately exotic and compulsive backdrop. In its small way, this sublimely engaging prototype martial arts fantasy did much to popularise and normalise the Japanese cultural idiom, but more importantly, it still reads superbly well today.

Rounding out this resurrection is an informative treasure trove of extra features comprising creator biographies, sample script pages, art breakdowns layouts, pencilled pages, promo art and portfolio illustrations. A fondly reminiscent, informative Afterword from Potts reveals him in the laborious process of transferring Last of the Dragons from page to screen.

This is a magically compelling tale for fantasy fans and mature readers. It’s an utterly delightful cross-genre romp to entice newcomers whilst simultaneously beguiling dedicated connoisseurs and aficionados renewing an old acquaintance.