Review by Ian Keogh

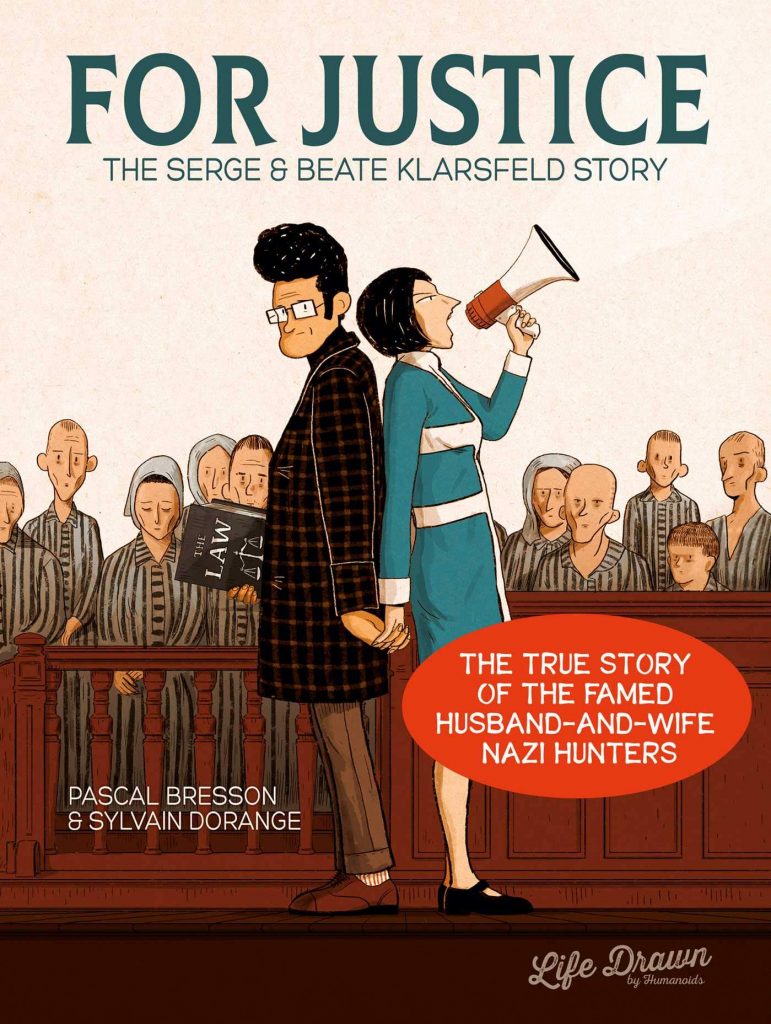

Within his introduction Serge Klarsfeld notes being asked to contribute to a series of books focussing on important historical figures whose influence isn’t as widely acknowledged as it ought to be. It’s of relevance because his story and that of his wife Beate falls into that category, much of their lives devoted to bringing World War II Nazis to justice when the authorities would rather forget.

Pascal Bresson and Sylvain Dorange adapt For Justice from the Klarsfelds’ 2016 memoir, and from the start they’re an unlikely couple. When they meet in 1960 Serge is a Parisian history student with Jewish ancestry who remembers being hunted during World War II, and Beate is a German au pair who grew up being told to be suspicious of Jews.

It’s no longer known how many crimes were overlooked by a world keen to see Germany re-established after World War II. That nation was far from Nazi-free, with former high ranking party members slipping back into post-war life, and many with muddied records rose to prominence. Bresson mixes the early days of the Klarsfelds as a couple with their drawing attention to the wartime status of Kurt Kiesinger, elected German chancellor in 1966. How much their high profile tactics ensured he wasn’t re-elected can’t be ascertained, yet the complicity of the German authorities in ignoring the issue stands revealed by the astonishing revelation that one former Nazi was tracked down via his phone book listing. Beate and Serge also ensured that attempts to call a statute of limitations on monsters like Klaus Barbie failed.

There’s considerable precision to Dorange’s cartooning, especially with regard to cars and period furnishings. Rather than focussing on exact likenesses, his expressive line arranges for approximations, with Beate sharp-featured reflecting her proactive personality. Serge is portrayed with a formidable quiff, and over the early years of their campaign as more passive, a researcher rather than a fighter. Just as the Klarsfelds are well aware how powerful a staged moment can be, Dorange occasionally departs from the friendly cartooning for a memorable visual allegory, the most notable being the ghosts of the dead floating in a courtroom.

Compacting considerable amounts of information leads to sometimes awkward dialogue, explanations for the reader, not the person addressed, but Bresson brings through the conviction and ingenuity employed in the Klarsfelds’ successful campaigns. They are remarkably hands on, on more than one occasion attempting abductions to bring Nazis to justice. The inevitable result is that they become targets for those determined secrets remain hidden.

The comics portion of For Justice ends with the Klarsfelds interviewed and reinforcing that governments around the world had no interest in hunting war criminals, and only the efforts of individuals resulted in justice for the murdered and persecuted. It’s some condemnation.

Readers with a humanitarian conscience, yet unaware of the specific history should find Beate and Serge’s story every bit as suspenseful and fascinating as readers who know some names and details. The Klarsfelds practiced a form of activism that more people should be aware of, and they end concerned that no lessons have been learned and fearing the 21st century rise of the right throughout Europe.