Review by Win Wiacek

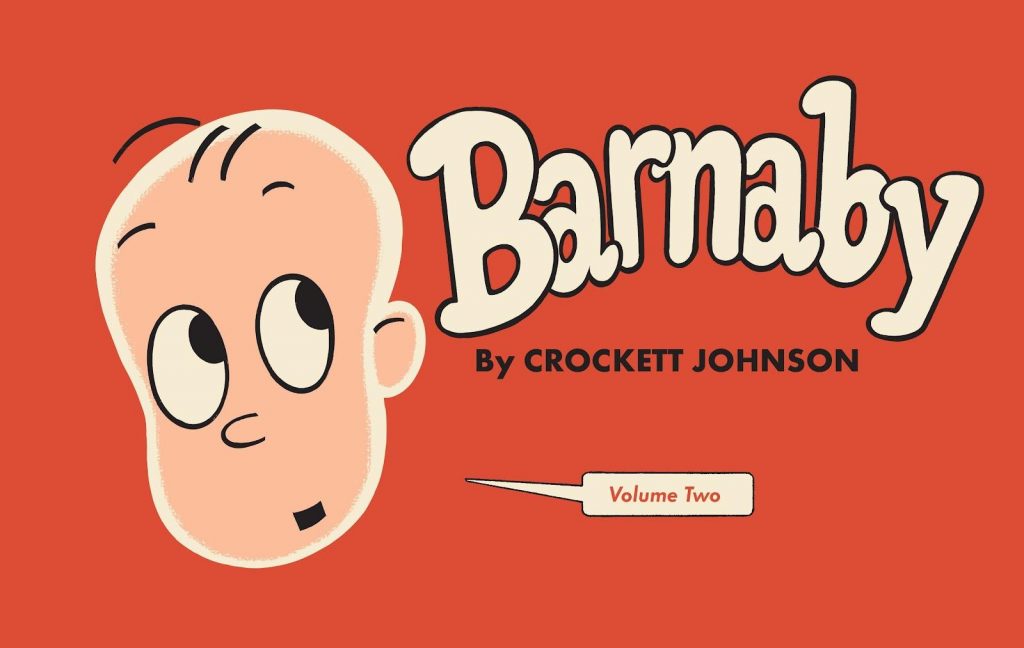

The captivating first volume of Barnaby reprinted just under two years worth of Crockett Johnson’s newspaper continuity, leaving this selection to pick up in January 1944, running to December 1945.

Barnaby is a sweet, smart and honest pre-schooler who one night wished for a Fairy Godmother. What he got was O’Malley, who technically qualifies, but is a lazy, self-aggrandizing, mooching old glutton and probable soak.

At the end of the first volume O’Malley implausibly – and almost overnight – became an unseen and reclusive public Man of the Hour, preposterously translating that cachet into a political career by accidentally becoming a patsy for a vast and corrupt political machine. In even more unlikely circumstances O’Malley is then elected to Congress, which somehow doesn’t seem so fantastic any more.

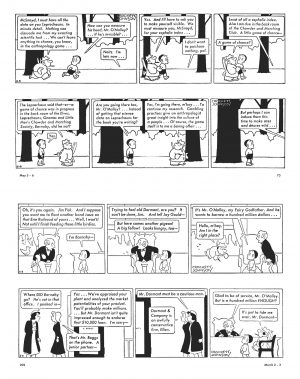

Once O’Malley has his foot in the door – or rather through the bedroom window – a succession of bizarre characters start sporadically turning up to baffle and bewilder Barnaby and Jane Shultz, the sensible little girl next door. Even the boy’s new dog Gorgon is a remarkable oddity. The pooch can talk, but never when adults are around, and only then with such overwhelming dullness that everybody listening wishes him as mute as every other mutt.

Other mythical oddballs and irregulars include timid ghost Gus, Atlas the Giant (a 2-foot tall, pint-sized colossus who is a mental Giant) and Launcelot McSnoyd, an invisible Leprechaun. He’s O’Malley’s personal gadfly: always offering harsh, ribald home truths and counterpoints to the Godfather’s self-laudatory pronouncements. Johnson continually expands his gently bizarre cast of gremlins, ogres, ghosts, policemen, Bankers, crooks, financiers and stranger personages – all of whom can see O’Malley – but the unyieldingly faithful little lad’s parents are always too busy and too certain the Fairy Godfather and all his ilk are unhealthy, unwanted, juvenile fabrications.

Johnson despised doing shoddy work, or short-changing his audience. On average, each of his daily encounters – always self-contained – built on the previous episode without needing to re-reference it, and contained three to four times as much text as its contemporaries. It’s a sign of the author’s ability that the extra wordage was never unnecessary, and often uniquely readable, blending storybook clarity, the snappy pace of “Screwball” comedy films and the contemporary rhythms and idiom of authors such as Damon Runyan and Dashiel Hammett.

During a global war with heroes and villains aplenty, where no comic page could top the daily headlines for thrills, drama and heartbreak, Barnaby was an absolute panacea to the horrors without ever ignoring or escaping them.

For far too long Barnaby was a lost masterpiece. It is influential, ground-breaking and a shining classic of the form. You are all the poorer for not knowing it, and should move mountains to change that situation.