Review by Woodrow Phoenix

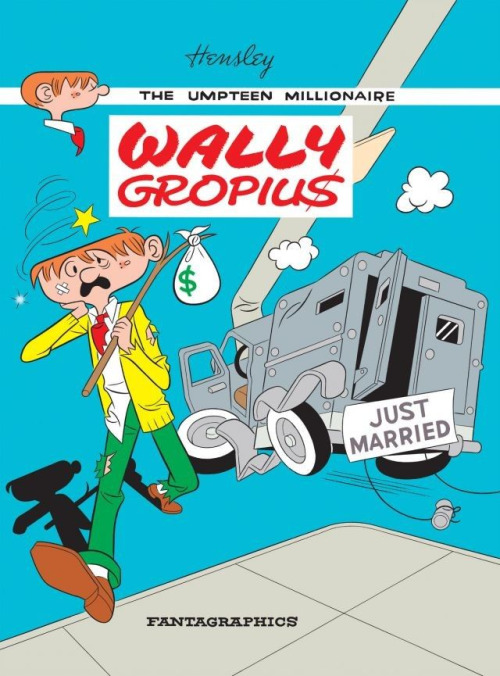

There’s a lot going on beneath the bright and cartoonily abstract surfaces of Wally Gropius. The large hardcover is designed like a traditional French comics album with its swashy 1960s logo, the flat colours, and the cloth spine, but the drawing of the title character is all USA, a straight blend of Beetle Bailey, Nancy and Archie. It’s almost a perfect retro confection, but like the weird geometry of the cover image, something about the mixture of styles is slightly off.

The titular young hero Wally Gropius (first running gag is that he has the same name as the famous Bauhaus architect) is the world’s richest teenager, with a butler who tunes his guitars for him and a roomful of back office peons doing the paperwork required for his every whim. His smooth lifestyle is disrupted when dad Thaddeus Gropius, fusty old boss of a global petrochemical conglomerate, tells him he has to marry the saddest girl in the world or be disinherited. When the news gets out every girl in school is suddenly loudly depressed or suicidal – except for one. From this very trad cartoon set-up Tim Hensley spins a story that can be read as a farce about attempted identity theft, a commentary on celebrity, gender norms and the commodification of everyday life, or a skilled and skewed parody of the kind of material that used to be mainstream entertainment in a different era.

Hensley obviously loves this period of comics. He has studied all the cartoon clichés and reworked them into an absurdist gagfest. His drawing riffs on the kind of exaggerated visual jokes and concepts that define wealth for characters like Richie Rich or Uncle Scrooge, but simultaneously undercuts them with ridiculous sound effects (‘Forbes’! ‘Kopeck’!) or puns (Wally’s ‘money launderer’ literally uses a mop and bucket). The characters don’t speak directly either. They announce, allude, declaim, speechify and confuse each other, each one in their own bubble that touches others at certain points. And where they touch, there are surprising, violent or appalling results.

Is it all just an art prank, this obsessive recreation of an attitude that no longer exists? Wally Gropius’ slick surfaces invite that reading. There’s at least one example of every type of cartoon in this book; daily strips, single panel gags with captions, one-page character jokes, watercolour editorial illustrations, value coupons, diagrams, and even the lettering of balloons, headers, logos and page numbers is carefully matched to the pretend sources. Then to top it all, there’s a page of the kind of photo collages Jack Kirby would make in the Fantastic Four when things became too cosmic for pen and ink. It’s a like a fetish object made in a lab. Wally Gropius wouldn’t work unless there was some solid foundation underneath it all, and Hensley’s plotting is direct with all the clues clearly shown. It’s an interesting way to demonstrate how a visual medium like comics can rely too much on dialogue to tell you what’s happening rather than let the pictures show you. Pay attention to what the characters do rather than what they say. You will solve the mystery without much trouble, if you aren’t distracted by the way Wally Gropius seems to crash into a wall of its own self-aware illogic at the end.