Review by Ian Keogh

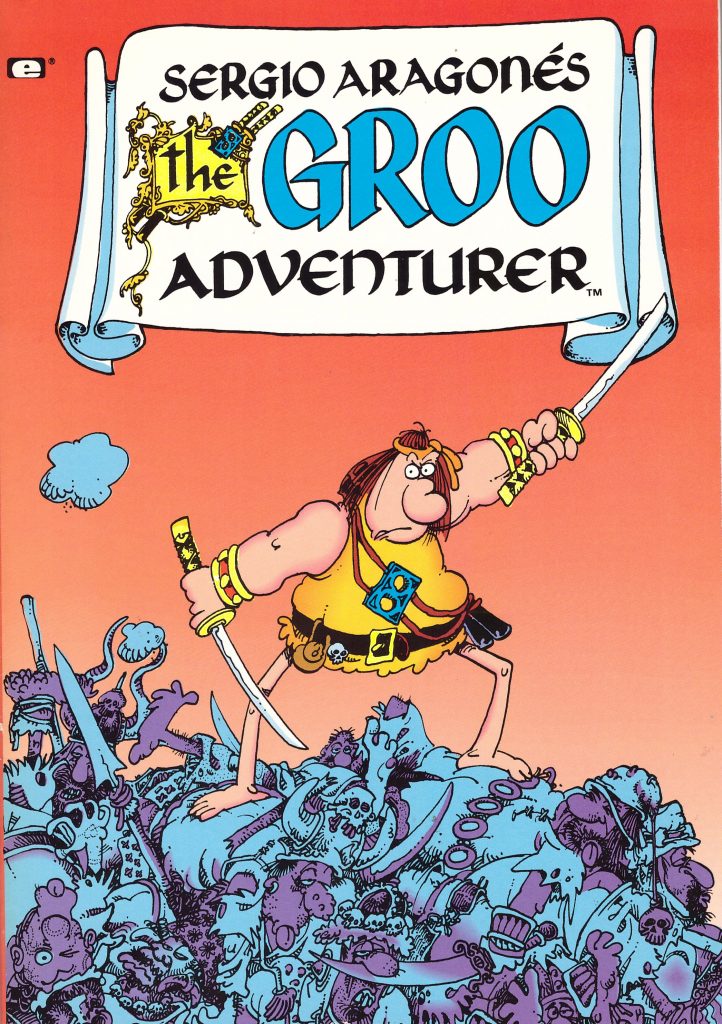

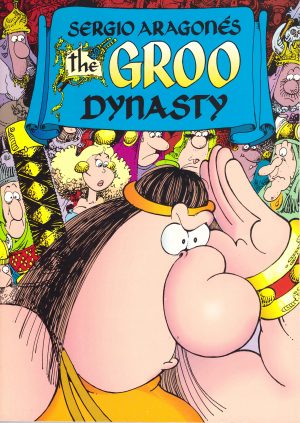

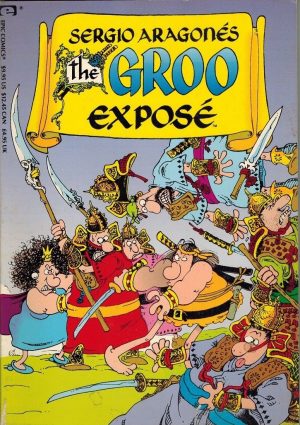

Considering that Groo the Wanderer has now run for over 35 years, and is also creator-owned, the haphazard nature of what’s available as graphic novels, in English at least, is surprising. The Groo Adventurer is long out of print, and while the earliest collected Groo content when it was on shelves, it still only picked up with the third year of Groo’s wanderings. Look at it however, and it could almost be the most recent Groo collection, so little has the format changed. When Groo first appeared in 1982, Sergio Aragonés already had twenty years of working for Mad Magazine behind him, while Mark Evanier’s long TV writing career was already entering its second decade, and that experience and polish is evident.

The premise is simple. Groo is a barbarian, in his own way as fearsome as Conan (who he’d later meet), but completely dim and incompetent. There aren’t many partnerships of man and dog where the four legged unit is the smarter one, and there’s no situation that can’t rapidly deteriorate with Groo’s presence. He’s a formidable swordsman, but his is a simple life. Give him some cheese dip, avoid calling him a mendicant, and point him in the direction of a fray and he’ll be relatively content. These adventures occur before Groo met his dog, Rufferto, but introduce the Minstrel, whose rhyming musical proclamations would regularly test Evanier’s skills (and the audience tolerance for a pun), and begin the tradition of Aragonés always changing the object fixed to the Minstrel’s lute. The Minstrel makes his bow singing brief tales of Groo’s ineptitude, as good an introduction as any to the feature, each perfectly crafted and hilarious illustrating Groo’s stupidity. Also introduced is Taranto, who’d later be a bandit, but here serves a King.

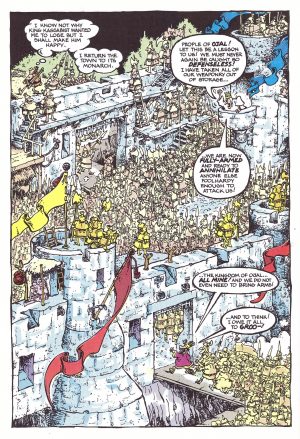

Famed for his ‘Mad Marginals’, little visual jokes between the panels in Mad, Aragonés’ career was already marked by the density of his cartooning, but even knowing that, the sheer amount of background detail in Groo still astounds. This isn’t a few round shapes to indicate a crowd, but entire fully formed spreads, each the complete Breugel picture of village life, every person’s pose and expression different. Furthermore, if you want to play the game, somewhere amid all the detail, there’s a hidden message. It’s generally just the phrase “this is the hidden message”, but on occasion, such as the second story, it’s more creative, tying into Aragonés basing a character on his fellow Mad artist Al Jaffee. In his afterword Evanier explains a further long-running tradition.

Aragonés and Evanier deliberately muddy the credits, with Evanier often joking he doesn’t know what he does on Groo, and certainly doesn’t get paid for it. It’s his clever dialogue, however, that characterises the feature as much as the art, making running jokes of obscure terms, and creating distinctive voices for Aragonés’ distinctive creations.

The misfortunes of others is a comedy cornerstone, and there’s no misfortune like Groo coming to town. The stories are all ages, beloved by adults and children alike, and continue with The Groo Bazaar.