Review by Karl Verhoven

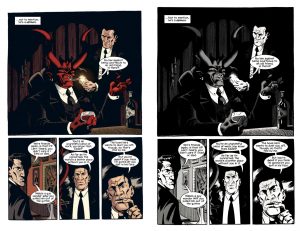

Eddie is an unashamed gangster in prohibition era USA, one with an advantage other gangsters lack: he can’t be killed. Well, he can, but a short time afterwards he returns to life provided someone finds his corpse and touches it, transferring their life force. The title refers to his last spell among the deceased. He’s also in on a secret not known to many of his contemporaries, which is that 1930s gangster culture is actually controlled by demons. The big bad boss seen on the sample art is Alphonse Aligheri, Cullen Bunn’s nod to one of the earliest fictional depictions of hell, but there are others and there’s a constant dance between them for total control of the rackets. When a demon brokering a peace deal disappears, it’s a major problem, but one that might just offer Eddie a way out. “That’s what I like about you Eddie, you’re always thinking,” he’s told, “So I want you to think about this. You take care of this for me, and you and me are square.”

A poor sap given one final job that will possibly set them free is a fictional standby that rarely ends well and generally throws up plenty of complications. Having established the originality in setting up his scenario, Bunn slips back to double-crossing, gangster noir familiarity for much of what follows, but he’s established enough intrigue to carry us along as Eddie searches for answers.

Brian Hurtt also receives a story credit, so presumably had some input beyond his nuanced art, which somehow never received the attention and praise it should. Hurtt is an excellent storyteller, with a compact definition to his pages. There’s no unnecessary flash about them, but everything needed to tell the story well is there, and he conveys a mood excellently. A nice touch is that Eddie may come back to life, but as drawn by Hurtt he bears the scars of his previous deaths, and many artists wouldn’t bother differentiating the dozens of demons who feature, but Hurtt takes the time to do so. As seen in the sample art, his Aligheri is especially distinctive.

The novelty is the intrusion of demons in a gangster story, and while the plot is never predictable, it’s not one intended as a puzzle for readers to figure out, as some information Eddie learns is deliberately kept from us. There are enough anomalies introduced to sustain Three Days Dead, but it never quite grips as it should, possibly due to Eddie being very one-note and not entirely sympathetic.

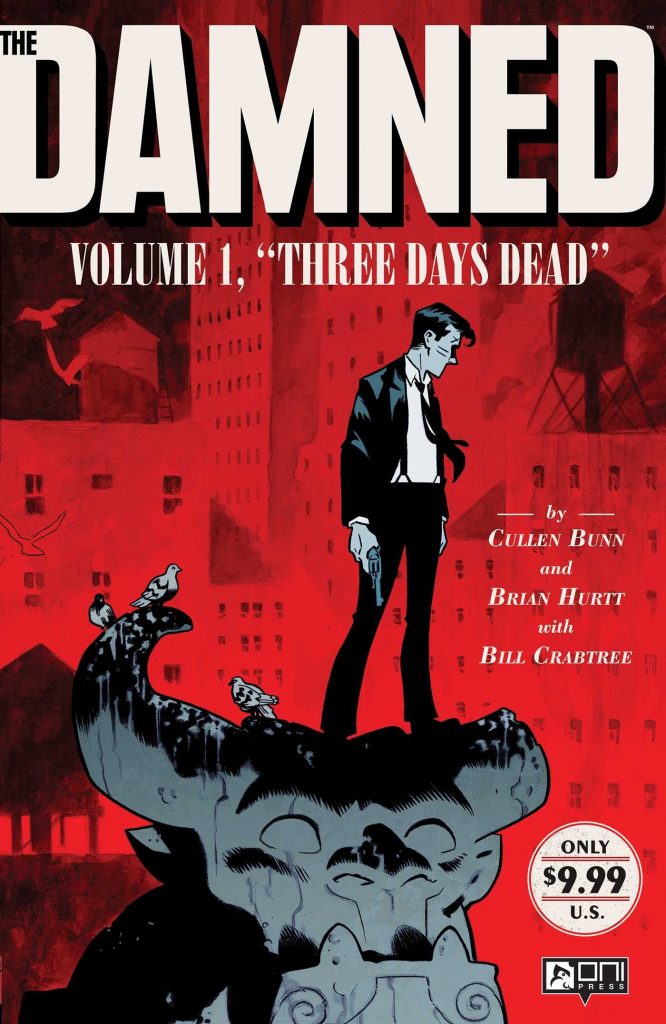

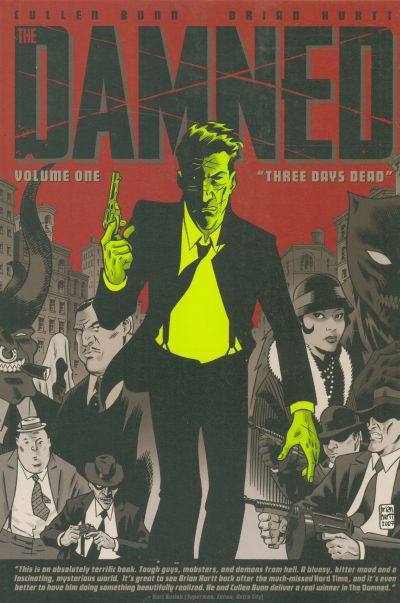

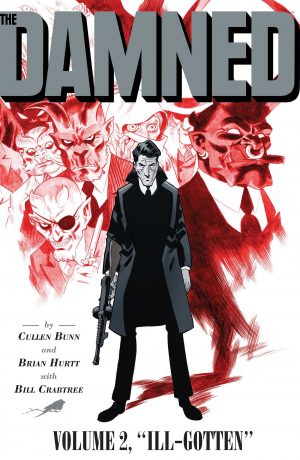

Three Days Dead was originally published as a black and white collection, but when Bunn and Hurtt returned to the idea after almost a decade it was reissued with Bill Crabtree’s colouring added. Colouring work originally intended for monochrome doesn’t always work well, but by limiting the colours Crabtree adds a new vibrancy, although the current edition matches the dimensions of the sequels, and so is slightly smaller than the first black and white trade. Ill-Gotten follows.