Review by Frank Plowright

Art Spiegelman worked on Maus for over a decade prior to the first chapters appearing in book form in 1986. A prototype four page strip dealing with his mother’s suicide (reprinted here) dates back to 1973, and serialisation within the pages of his Raw anthology from 1980 followed.

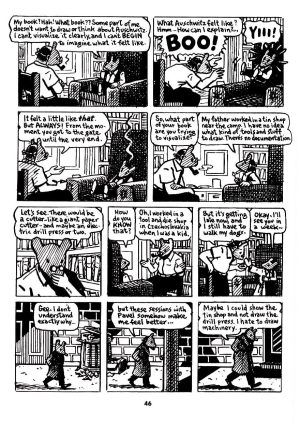

Had he not already used it, Raw would have been a valid title for this exploration of the fractious relationship between father and son, and the paternal experiences during World War II. The combination of horrific occurrences and family dynamics is a rich seam of exploration, and while Spiegelman’s background was from a sphere that embraced autobiographical intrusion in comics, his material had previously prioritised formal experimentation (see Breakdowns).

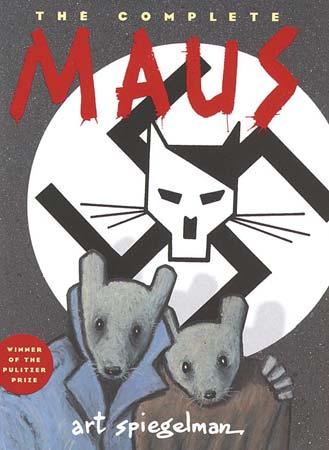

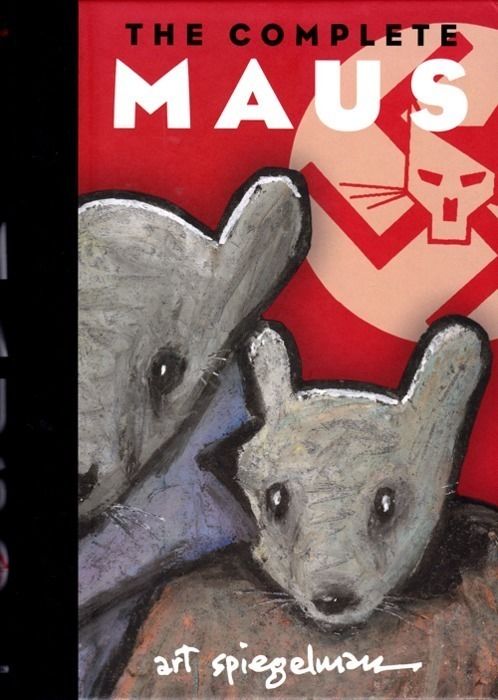

There are two narrative strands to Maus. The interaction of the present day has Art attempting to prise very painful recollections from his father, and in the 1940s we have Vladek’s experiences first in Poland occupied by the Nazis, then as a Jew in Auschwitz concentration camp. The title originates in the distancing technique Spiegelman employs by classifying races as forms of animal, with Jews depicted as anthropomorphic mice. Cats portraying Germans is a natural extension, but the metaphor expires by the time we have Poles as pigs.

The opening chapter indicates the relationship between father and son. It’s noted that it’s been a long time since Art and Vladek saw each other (despite both living in New York), and after relating the circumstances of how he met his wife Vladek explicitly requests the material not be made public. Despite the previous gap between visits, with a mission of further revelations Art can now regularly visit his father. This could be interpreted as a desire to repair a connection long lapsed, but is conveyed as self-interest.

Vladek is contrary, miserly, over-bearing and unable to process the viewpoints of others. Why not throw out Art’s coat and replace it with a new one because he believes it’s tatty? Yet this can be reinterpreted as uncharacteristic generosity in the light of later exhortations to stop wasting matches. As his horrific recollections continue it prompts the examination of how any of us would have survived the persecution and constant fear of death he abided without also becoming twisted. It’s noted, though, that others have, without becoming Vladek. While not on the same scale, it also prompts us to wonder how anyone could live with the man those events shaped. As much as Maus is about what Vladek endured, it’s also a purge for Art.

For all the weighty Pulitzer Prize winning expectation attached to Maus, it’s an eminently readable book, both narratives related in simple fashion via almost sketched art that’s persistently strong on emotional resonance and detail. Interspersing the horrors with the frustrations of later life with Vladek leavens what might otherwise have been relentless misery, but a melancholy air prevails throughout. Similar top rank honest and harrowing autobiographical depictions of family life have followed (Epileptic, Fun Home, You’ll Never Know). These haven’t diminished the power and achievement of Maus, which remains the seminal achievement it was hailed when first published.

The original publication was as two volumes, subtitled My Father Bleeds History and And Here my Troubles Began. 25 years after the first book publication, Spiegelman compiled much of the research and background materials along with interviews about the project as MetaMaus.