Review by Roy Boyd

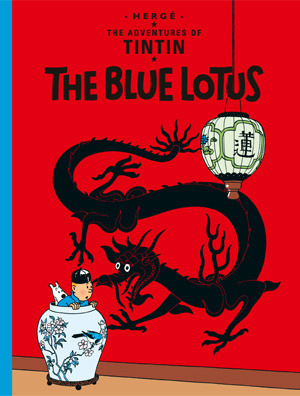

Coming after Cigars of the Pharaoh, The Blue Lotus was to represent a great leap forward in quality for the Tintin books. This was the first book that was properly plotted, rather than being worked out on a weekly basis, and the improvement is readily apparent.

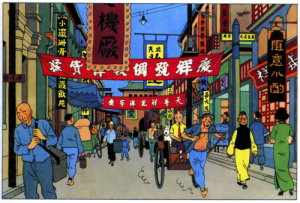

The second reason behind the improvement was Hergé’s introduction to Chang Chong-Chen, a young Chinese student living in Belgium. Their meeting had been arranged by a Catholic priest concerned about the inaccuracies in the previous Tintin books, who wanted to ensure that the next adventure, to be set in China, wouldn’t make the same mistakes as its predecessors. Chang oversaw the design of many items in the book, and introduced Hergé to many aspects of his country’s culture. From this point onwards the grateful artist always “really interested myself in the people and countries to which I sent Tintin, out of a sense of honesty to my readers.”

In this, the first openly political Tintin story, set against the historically accurate backdrop of the Sino-Japanese war, Tintin witnesses Japanese agents conducting a false flag operation, staging an attack on their own soil by the Chinese so providing a reason to move into China. Unusually for someone in the western press at that time, Hergé came down firmly on the side of the Chinese, no doubt influenced by his friendship with Chang. This resulted in the Japanese complaining to the Belgian government. However, Hergé was secure in the authenticity of his work, and history was also to prove him right when, just seven years later, the Japanese launched their sneak attack on Pearl Harbour.

The carefully structured plot contains all the trappings expected from a pulp detective story of the period: opium dens; chloroform; drive-by shooting; kidnappings and a poison that causes insanity. And it contains many of the handy plot devices you’d expect too, from overheard conversations to conveniently dropped business cards at crime scenes. One notable exception to the list of pulp ingredients is the lack of a femme fatale, or attractive women in general. There are a few women in the Tintin books – Bianca Castafiore being the most obvious, and she’s a monumental pain in the arse – but one would struggle to think of a really positive portrayal of a woman in any Tintin book.

Chang appears as a character, when Tintin rescues him from drowning, and they have a discussion about the ignorant beliefs many Westerners hold about the Chinese, making a pointed comment about Hergé’s unthinking acceptance of stereotypes. We also have a scene where Tintin stops a Westerner beating a native. Needless to say, this encounter follows the law of conservation of characters, with the arrogant Westerner revealed as one of our villains, and the grateful native’s brother later helping Tintin out of a jam.

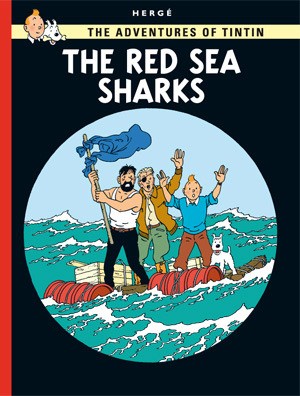

Chang was to reappear in Tintin in Tibet, and Rastapopolous, another member of the ever-expanding Tintin family, returns from Cigars of the Pharaoh, though he escapes and isn’t seen for another twenty years until The Red Sea Sharks.

While some of the artwork is loose compared to later books, many fans consider this the first of the excellent Tintin books, and some consider it Hergé’s best work. However, Methuen thought that the contents were so topical it would date badly, and they didn’t release it until 1983, the year of Hergé’s death. Their concerns have proven unfounded, and this book is now rightly considered a classic.