Review by Ian Keogh

Can anything positive be said about any organisation involved in the disintegration of the Yugoslav state from 1989 onward? Monumental humanitarian failure saw alleged United Nations peacekeepers permit racist thugs to continue their murderous activities unabated while their leader was courted rather than indicted. It seemed bad at the time, and as the truth began to emerge in the mid-1990s it became unconscionable. War continued longest in Bosnia, but while the diplomatic failure of Sarajevo received some international attention, other areas of the country were largely ignored. Joe Sacco’s contemporary reportage concentrated on Bosnia’s east.

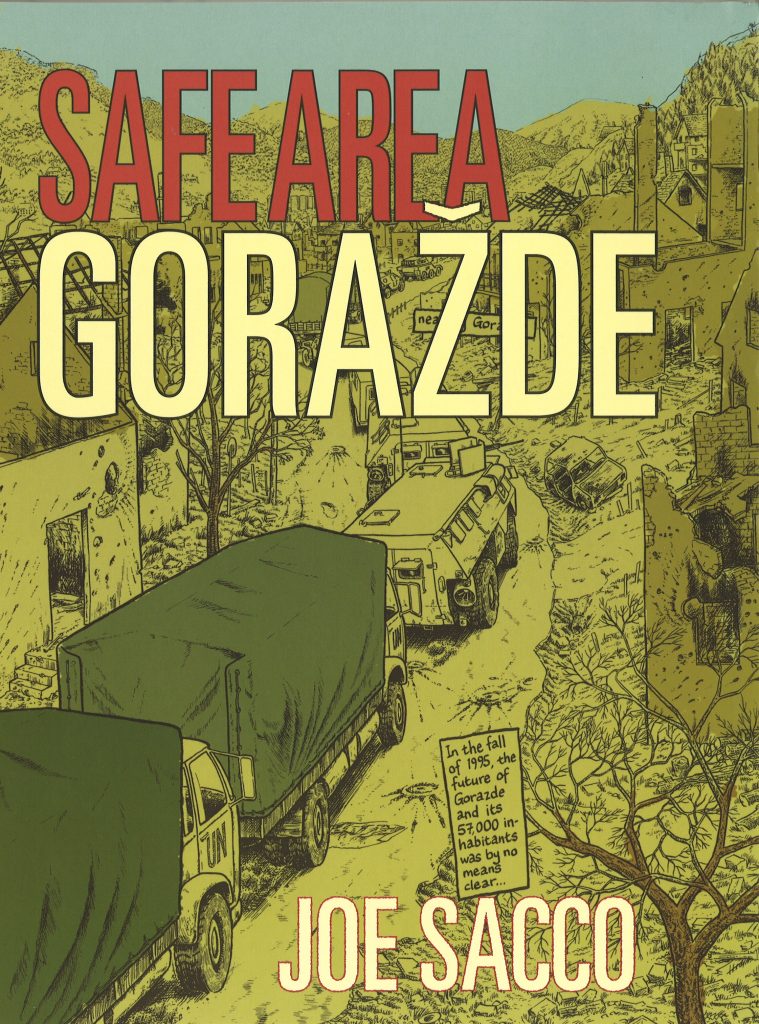

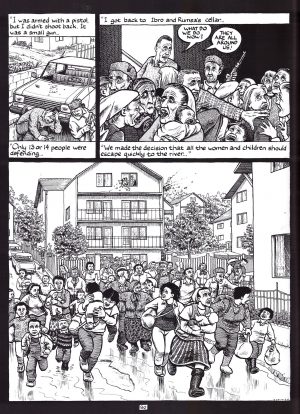

Early on he outlines a nation of mixed peoples and religions living together in relative harmony for almost fifty years before reviving the grudges of their grandfathers from World War II. It begins a system of black bordered pages dealing with historical events and personal recollections while the illustrations bleed off the page for the present of 1995. In 1995 Goražde was an enclave, a town of just over 20,000 swelled to 57,000 trapped Bosnian Muslims surrounded by Serb forces, the final such area after the UN had abandoned two others to their horrific fate. Sacco is among the journalists accompanying the first UN mandated supply convoy to enter the city under agreement. In the company of technical engineer Edin he tours Goražde, listening to ordinary people and hearing what they’ve been through.

Their experiences are fear and atrocity, ethnic cleansing in the name of unification, and it takes a supernaturally calm and rational person to mask their outrage in the name of understanding. Goražde is a city whose only electricity is generated by home-made paddle contraptions on the river, and with food in very short supply until the UN convoy. Sacco’s visit coincides with peace discussions, and a fear that at best the city will remain an enclave in Serb territory, the only connection with the remainder of Bosnia a single road constantly blocked by Serb troops. In addition to his observer status Sacco becomes a messenger and package courier.

Christopher Hitchens in his introduction notes the restriction of bile, but Sacco is astute enough to prevent Safe Area Goražde being a catalogue of atrocity, sifting testimonials of the barbarity among his experiences of everyday life, of people complaining of boredom due to lack of outside influence. His points are made, however, by illustrations of empty school desks, of distinctive bear claw mark shell pits and every street with burned out cars. Sacco’s a stickler for detail, for the clothes people wear, for the ubiquitous bullet holes in the walls, for the plain furnishings and for the lovely landscape. Remove the corpses floating in the river and some of Sacco’s townscape illustrations would grace any wall, but that’s not the point. Most people he meets are bewildered how their Serb friends and neighbours could transform overnight, but a scene of some briefly returning indicates the pressure they were under, and that they didn’t all become monsters. A later sequence concerning a Serb who remained in Goražde concludes with several people being asked if they could live with Serbs again. The most telling comment concerns Serbs being obsessed with history.

Safe Area Goražde is now history, yet significantly less time has elapsed between 1995 and now than had between 1945 and 1990, and the world is now far more fragmented. It means the book has become not just a series of recollections, but a warning about the dangers of demonisation, and so as relevant as it ever was.