Review by Frank Plowright

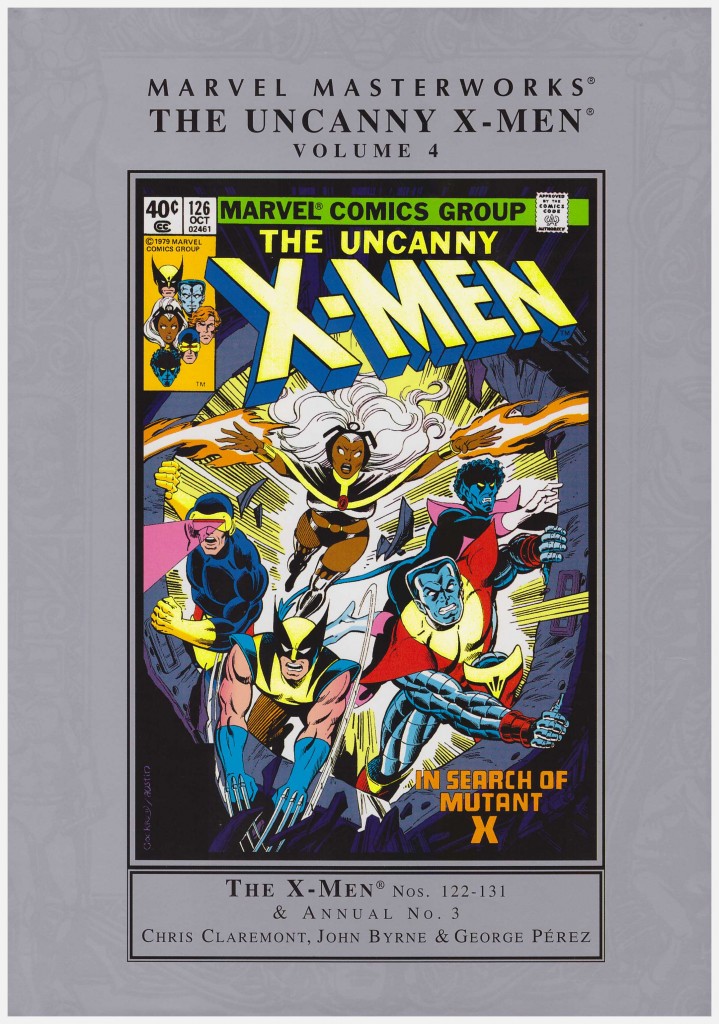

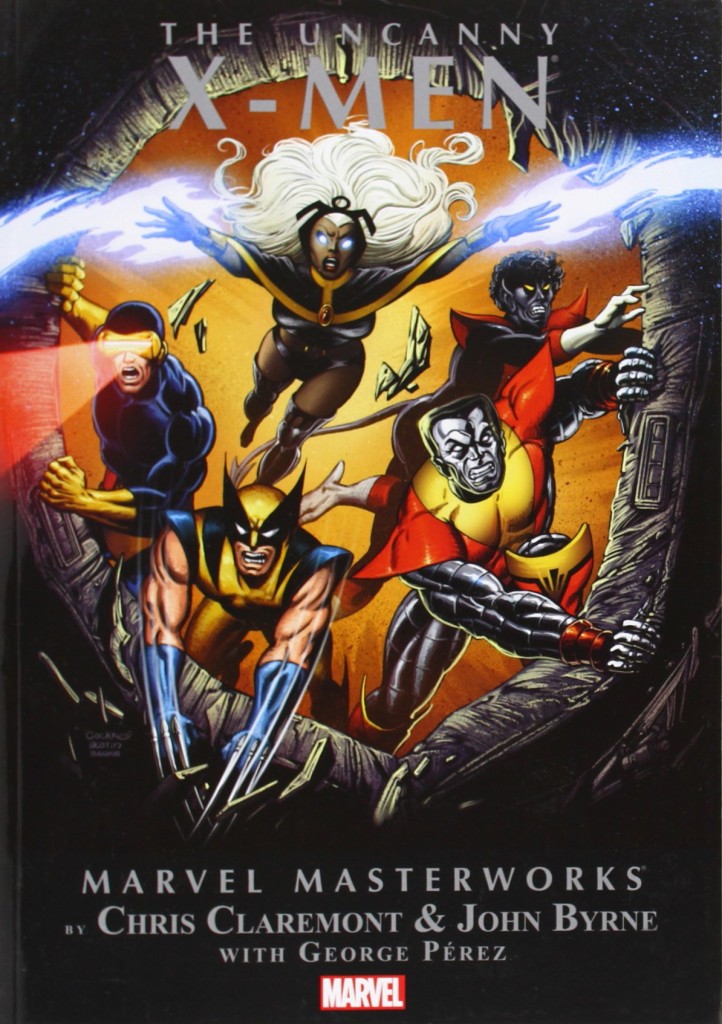

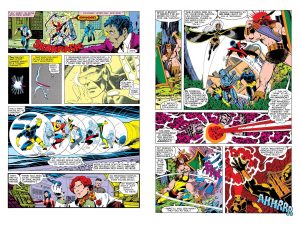

By the time of this collection of material from the late 1970s the team of Chris Claremont and John Byrne were really cooking with gas. Claremont notes in his introduction that the goal was “to have fun and tell great stories the best way we knew how,” and for all the well-worn and dashed off marketing cliché of that phrase, the evidence bears him out. The pair plotted in collaboration, each bringing out the best in the other, and Byrne’s graphic dynamism still looks good today, his enthusiasm shining through.

A brave story element was to separate the X-Men in a story collected in volume 3, with each party believing the other had perished, and to perpetuate this for a year during the publication of the original monthly comics. The reunion between Scott Summers and Jean Grey, alternatively Cyclops and Phoenix, is particularly well played against expectation. Readers are aware that someone is messing with Jean’s head, and the creators play fair by dropping a heavy hint to the observant when Jason Wyngarde is introduced, and repeating their clue in the penultimate chapter.

That element comes to full fruition in the next collection, but there’s plenty to distract here including the introduction of several characters who’d be integral to the X-Men. Kitty Pryde makes her debut in the final chapters, deliberately re-introducing the element of youth to the X-Men, and those also bring us the Hellfire Club. That’s a curious nod toward the 19th century gathering of debauchery, replete with fetishistic costumes. Dazzler’s association with the X-Men has been more sporadic, but when forced to include a marketing-led, disco-based super heroine whose powers were a lightshow, Claremont and Byrne exceed expectations.

Before those issues there’s a hunt for a malicious energy-sapping creature Proteus perhaps extended a little too far, but also later issued as a separate collection. Neither should one look too closely into the logic of Heath Robinson inspired execution specialist Arcade. Both provide better than average thrills despite their limitations. There’s also the fundamental flaw with alien warlord Arkon, never a man to avoid starting a fight by taking something he’d probably be given if he’d only ask. His story is drawn by George Pérez, an artist similar to Byrne in relishing packing his pages with as many characters as possible. Yet for all the detail there’s never a sense of those pages being crowded, and the bonus is that it distracts from the occasional piece of askew anatomy.

Previous volumes had incorporated solid characterisation, but the soap-opera elements escalate here, with only Nightcrawler avoiding an unpleasant personal surprise. Because so much was being handled correctly, there was obviously a light editorial touch, and the one noticeable drawback is the increasing verbosity of the scripts. All too often expository dialogue is the order of the day, and while not intrusive, amid such well-defined superhero action, it’s certainly apparent.

The entire content can also be found in Uncanny X-Men Omnibus volume one, and in volume two of Essential Uncanny X-Men. In the latter case it’s in black and white on pulp paper.