Review by Frank Plowright

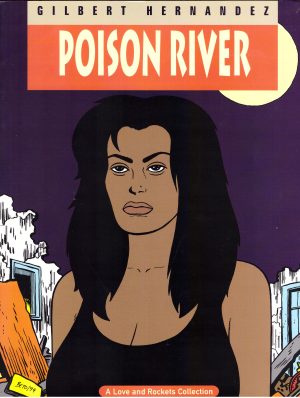

After completing the emotionally draining masterpiece collected as both Blood of Palomar and Human Diastrophism, Gilbert Hernandez took a break from his Palomar cast other than Luba, whose tragic backstory he presented in Poison River. He returned to Palomar in 1993, with a series of stories intended as a swansong, as indicated by both the valedictory feel of the material and titling one story ‘Farewell, My Palomar…’

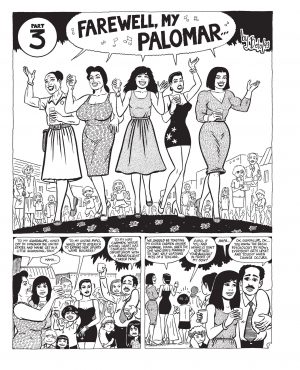

That moves events around ten years forward. Jesús is finally released from jail and returns home the long way, meeting friends and reminiscing as he goes, arriving in Palomar just in time for the party thrown for a number of people leaving for the USA. For anyone who’s read all the earlier stories this is a rich piece, overflowing with neat little touches new readers won’t appreciate (Khamo, the surfing kid) as Jesús catches up a decade in an afternoon. He also discovers he just can’t Luba go, much in the same way as Hernandez himself.

The middle section is the transition between Palomar and the later work Hernandez would produce about his cast members in the USA, and they’re nicely drawn with interesting moments, but don’t captivate overall. Yet just when you reach the conclusion it’s like a TV series hitting the fourth season when the creators have passed their cast on to others, Hernandez drops some searing insight. This is usually with the Palomar cast, as transplanting several others to the USA replaces an exotic background with a commonplace one.

Hernandez is still experimenting with his storytelling, four dense pages of Pipo’s recollections having the illustrations supplying a different narrative is nice, although Pipo is a rare Hernandez character who largely defies all attempts to make her interesting. ‘Mouth Trap’ is more straightforward, yet also a novel way of telling a story, featuring Luba’s sisters when children. This and several other stories concentrate on Luba’s mother Maria and her conflicted relationship with gangster Gorgo, now elderly, and a nice mixture of reality and unreality. They’re complex and compelling, characteristics missing when Hernandex later delved deeper into Maria and Gorgo’s stories in Maria M.

Luba might have thought she was now beyond surprises about her own life, yet the title strip proves otherwise when she discovers she has two younger sisters. It’s a wistful acknowledgement how even in Palomar life must progress, as represented by the town phone connection. Toward the end a couple of mysteries have solutions seemingly contrived just to be unlikely (the father of Guadalupe’s child), but the closer, ‘Chelo’s Burden’ is a magnificent piece, another career peak. The drama explains how closely Chelo is connected with the town, the truth behind some interesting manifestations, and much sadness passes without comment in the backgrounds. You’ll laugh, gasp and shed a tear.

These stories swerve all over the place, between past and present, Palomar and the United States, reality and other states, and what anchors them all is the phenomenally expressive art and Hernandez understanding so much about how people bump off each other. The better strips match his earlier peaks, and to moan about some being not quite as good is trivial. They easily sit beside the work of almost any other great storyteller working with comics. In later reprints these stories are absorbed into the bulkier Human Diastrophism collection, and most are found in the hardcover Palomar.

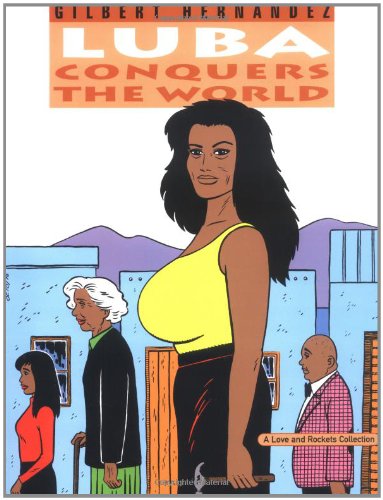

Although there are brief returns, Luba Conquers the World is Hernandez shedding Palomar, and splicing off the characters about whom he still has stories to tell, primarily Luba and her extended family. These begin in Beyond Palomar.