Review by Frank Plowright

We’re back in the bleak suburbia of Anytown, USA as the nihlistic and contemptuous Eric continues to pass judgement on others while his own lack of purpose leads him inexorably to the life he despises. That is if he doesn’t die first. He’s still withdrawing from the world beneath his papier mache fly’s head mask, his sense of entitlement festering within. He’s consistently provocative, directly to his mother’s boyfriend, indirectly with almost everyone else in his life apart from the one person who scares him.

Eric is just one member of an ensemble cast, each of them equally empty and unfulfilled, and generally masking their insecurities with aggression. Writer Michel Pirus’ technique is often to introduce someone through the eyes of another, then switch to revealing the truth of their own turmoil, or the facade they construct for themselves. It makes for a very clinical and compelling dissection.

Masks and costumes acquire a greater symbolism when we’re led down ever darker paths as Eric connects, tangentially at least, with more people and their solitary pursuits, while Pirus expands his cast. He swivels the spotlight to the older generation, also discontent and trapped, yet marginally more accepting of their existence, and he never forgets an item or an incident, with one grisly souvenir experiencing a gruesome reprise. Most surprising is the steps into the realm of the dead, beginning with the return of Damien, killed in the opening episode of King of the Flies, now perpetually trapped within the skeleton costume he wore for Halloween.

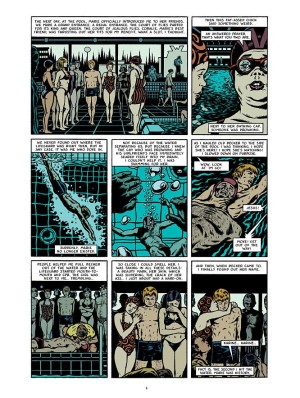

Mezzo’s art is superb at conveying the ennui and squalor of the world, providing a well characterised cast while throwing in surrealistic and unexplained images that work perfectly in this dissolute world. At one point Eric visits a former girlfriend who’s lying on a lounger cuddling a duck. A nine panel grid is the sole order in the runaway world depicted, and that discipline contrasts the escalating lack of control the cast have over their own circumstances.

As was the case previously, this is an extremely dense read, but Origin of the World improves on its predecessor. There’s a constant threatening undertone very cleverly perpetuated despite most of the cast being people you’d cross the street to avoid, and the effort expended in constructing the interweaving encounters is immense. This is now more clearly a suburban horror soap opera, with all the dramatic compulsion the form can induce. Such is the shock of the ending you’ll hear the Roland drums from East Enders in your head. It’s masterful.

King of the Flies concludes in Happy Daze, but sadly that book won’t be published by Fantagraphics, which is a great shame as outside Charles Burns no-one has dissected suburban squalor with such expertise. Don’t let the lack of a finale put you off sampling either this or Hallorave. Although there’s an ongoing continuity, so carefully has Pirus constructed them that each disturbing vignette works as an individual short story without reference to the remainder.