Review by Karl Verhoven

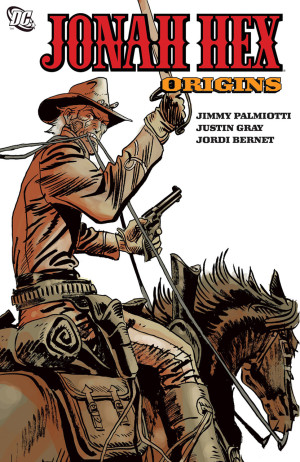

Just as the 1970s series about the horrifically scarred bounty hunter of a century previously was an often perverse and perennially under-rated treat, so was Justin Gray and Jimmy Palmiotti’s reboot from 2006. With Hex’s history pretty well mapped out, they dot back and forth to various periods of his life, enabling the option of whether or not to use established supporting characters. Over the series the same catholicity applies to the artists. The pseudo-photo realism of Luke Ross predominates in this collection, but there’s also room for a far grittier chapter by Hex’s artistic creator Tony DeZuniga, while later in the series the quixotic sketchiness of Jordi Bernet will sit alongside the impeccable cartooning of Darwyn Cooke, and the crowded kinetic action of Rafa Garres.

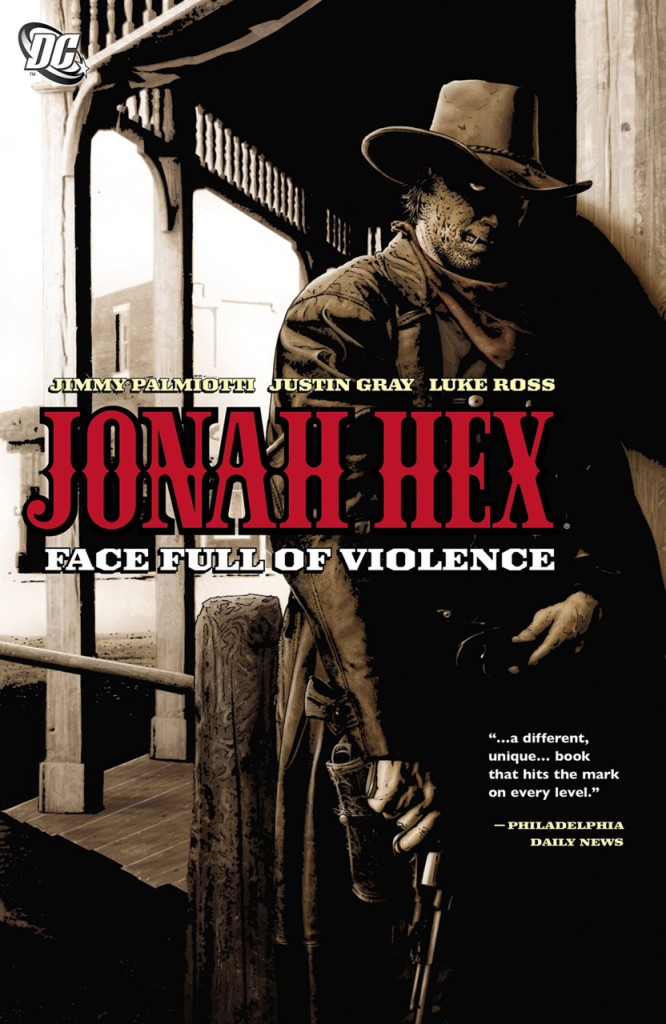

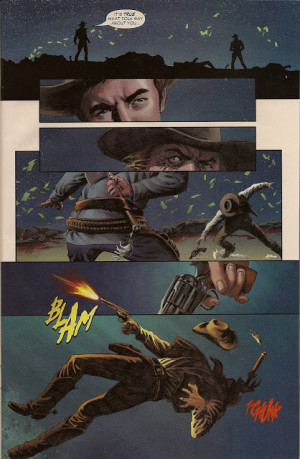

Oddly, it’s the opening artist selected for the series who’s among the weakest to work on it. Ross bases Hex on Clint Eastwood (and provides other Hollywood stars with cameos). His art is polished and refined, his storytelling dramatic, and during the more peaceful interactions he’s fine, but the look he brings is too clean and heroic for Hex’s world. It’s as if someone has spruced up the locations before Hex and his supporting cast set foot in them, and it’s mismatched with the grime and violence accompanying the character and his era.

There’s no such mistake about the plots. Gray and Palmiotti take their cue from Michael Fleisher’s 1970s work and deliver a gunfighter with a moral code, but one unafraid to do what’s required when transgressors cross a line. There’s no hand-wringing or moralising. If Hex kills someone they’ve had their warning and ignored it. Although none of their descriptions took hold like the 1970s summation of Hex’s companions being gunsmoke and death itself, the writers take a good punt at adding to the myth in their opening chapter. We have “He could say with every measure of confidence that God hated him. And to his credit Jonah returned the favor as often as he could”, or “Jonah took it upon himself to dispatch as many sinners as hell could accommodate”. It’s a conceit rapidly dropped, and the remainder of the book has stories told via dialogue alone.

Gray and Palmiotti have a handle on Hex as both a dispenser of curt one liners and an instrument of righteous vengeance, concocting suitable fates for miscreants, exploiters and ne’er do wells. They have him wandering the west dispensing his own form of justice to crooked carnival owners, dealing with an exploitative mining executive and risking a town quarantined for fear of plague with a surprising controller. There’s even an introductory meeting with Bat Lash, another endearing DC Western character, one who never achieved Hex’s level of popularity.

It may be slightly over-rendered in comparison with his work from the 1970s and 1980s, but Hex looks his best here when illustrated by DeZuniga in a resolutely unsentimental Christmas story. His cast are people who live hard and brief lives in inhospitable conditions in an era before plastic surgery, and when the violence occurs there’s the correct illusion of an un-choreographed reality.

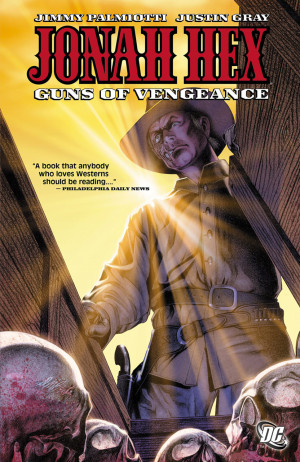

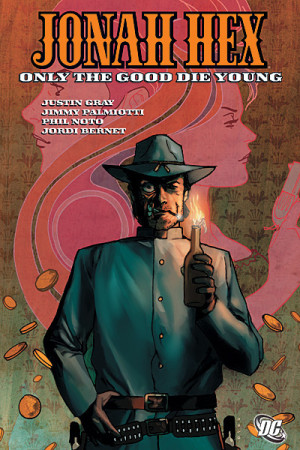

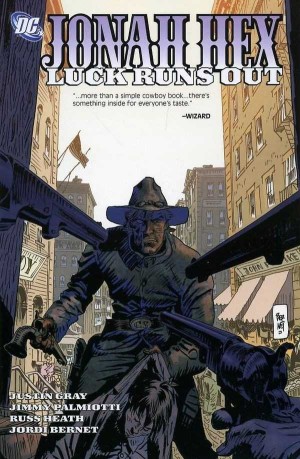

Mention should also be made of the clever volume title. Anyone who enjoys a good Western or who loved Hex’s earlier escapades can pick up this series confident of a good read. It continues with Guns of Vengeance.