Review by Karl Verhoven

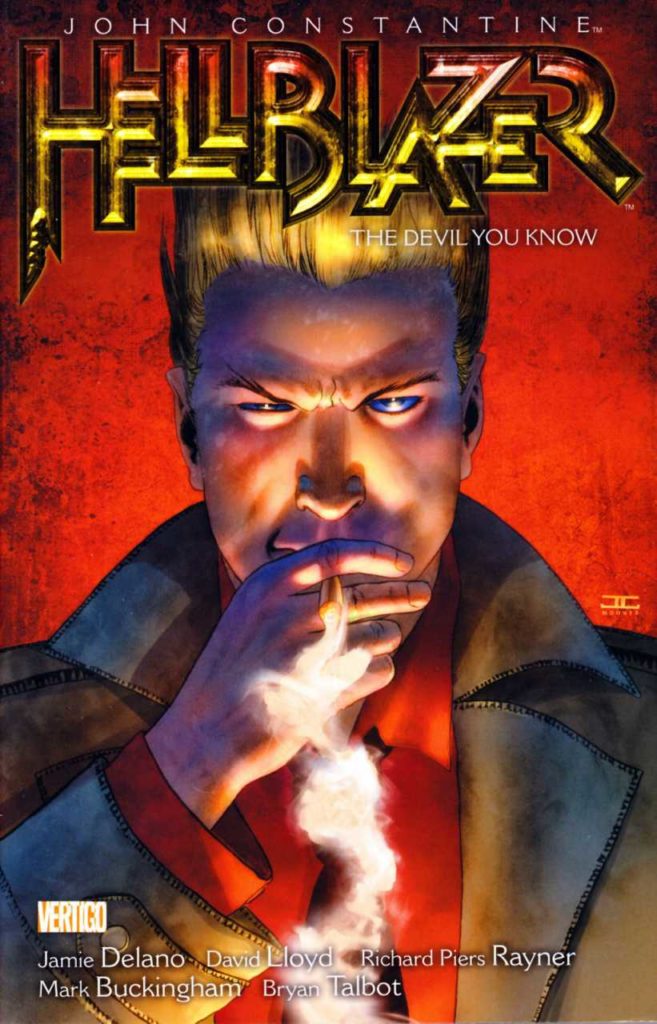

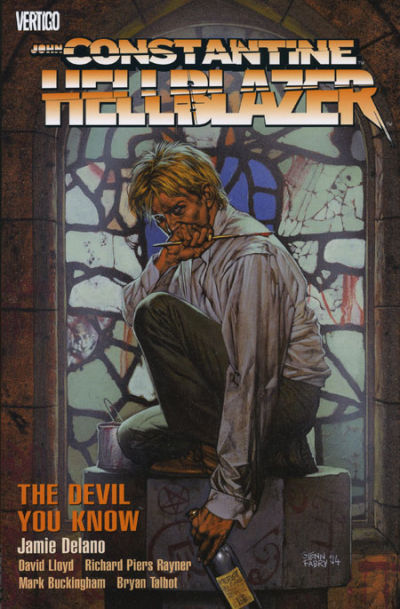

Considering the first nine issues of Jamie Delano’s Hellblazer run had been perpetually in print through numerous editions as Original Sins from 1992, a thirteen year wait to gather the next batch of his stories seems a missed opportunity on Vertigo’s part.

From his first appearances John Constantine dropped references to a tragedy that happened in Newcastle ten years earlier, and the full horror is revealed early in this collection, Delano tying an old grudge into his recent material. Winging it and dealing with the consequences defines Constantine’s career, and we learn it to have been his method from the start. It leads into a clever reappearance, and an enmity that continues long into the Hellblazer series.

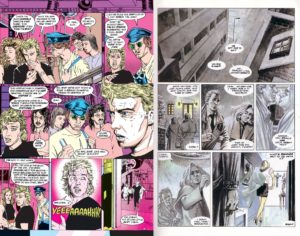

Compared with Original Sins there’s a sea change to the art, now offering the precision and immense background detail of Richard Piers Rayner. An occasional stiffness is the result of copious picture reference, but he must have laboured more hours than his pay cheque merited to create the vistas presented, often telling the stories in spreads. A different kind of detail is applied by Bryan Talbot in the shading and beads of sweat dripping off Constantine’s face as he remembers first arriving back in London after a spell in a psychiatric institution. That story tips abruptly into the past, introducing a mad sorcerer in ancient times. It’s nicely drawn by Talbot, and introduces themes followed up in The Fear Machine, but meanders.

Delano tells his stories via caption and illustration rather than dialogue, which is largely kept simple. The complexity is working his way into Constantine’s head, when he can go way over the top: “That was then. Before Thatcher. Before the Falklands War. Before the country – starving – ate out its own heart. Before hell impaled and roasted us, writhing over the roaring fires of our own inadequacies”. When Delano catches himself with “Christ, you’re such a morbid bastard Costantine”, there must be a hint of self-acknowledgement. Still, what could be cheerier than a trip to the seaside? Well, not under Delano. That seaside visit is trippy, ethereal and possibly symbolic, but not very accessible.

‘The Horrorist’ looked like no other Constantine story to that point, and is inordinately bleak, even by Delano’s standards. It removes Constantine completely from his comfort zone by taking him to Minnesota in winter where one tragedy is following another, Delano’s intensity superbly conveyed by Lloyd’s understated care. At heart it’s about a child rescued from famine compelled to bring disaster wherever she goes by the redistribution of suffering, and Constantine’s infinite capacity to repress it. It’s clever, but overwritten, leading to an extraordinarily detached ending.

Due to various pagination concerns over later collections, The Devil You Know is a strange, mixed collection of clashing moods and tones. It has its moments, but matches neither the collection before or after, which is The Fear Machine.