Review by Ian Keogh

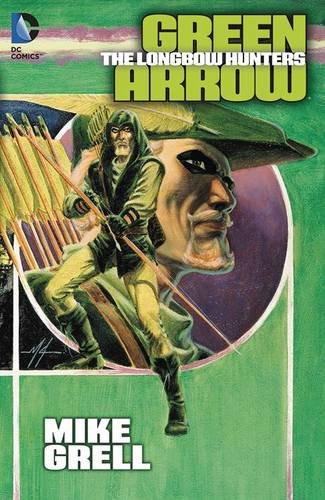

The Longbow Hunters has a history that it’s better divorced from. It was one of the earliest ‘serious’ releases to follow The Dark Knight Returns at DC, utilising the same format at a time when production values influenced expectation. Instead of a genre-busting redefinition of a classic character, Mike Grell tweaked Green Arrow to produce a different type of adult drama, one rooted in cinematic action hero tropes. What it now has in common with The Dark Knight Returns is that it still holds up well a few decades after the original publication.

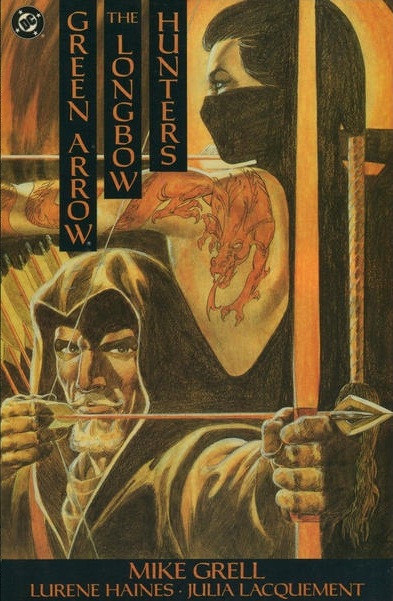

It may have lacked critical appreciation, but The Longbow Hunters was a commercial success in 1987, and Grell’s acquisition of a second string character prompted not only a series that ran for ten years (starting with Hunter’s Moon), but ensured Green Arrow’s name has subsequently headlined a regular comic ever since. He also introduced Shado, an archer with a complicated back story who became Green Arrow’s first recurring foe worthy of the name. This was all within a tautly plotted thriller in which everything ties together very satisfactorily.

Over an opening twenty pages Grell moves Oliver Queen (Green Arrow) and Dinah Drake (Black Canary) to Seattle, tours their new domestic arrangements, runs through Green Arrow’s origin, and establishes both a drug problem and a serial killer in the city. Some scenes draw on previous material, acceptably incorporated into a re-boot, and supplemented by new elements. Commonplace now, the focus on tattoos in the 1980s was novel, as was the introduction of Japanese culture as a background element. A further notable aspect is Grell acknowledging the age of his lead characters, noting Oliver Queen as 43 and occasionally feeling it. His other modifications to Green Arrow are relatively minor. There’s a new costume more suited to Seattle’s colder climate, and out go the trick arrows as Grell’s aiming for a form of realism in which they have no place. Interestingly, neither does the Green Arrow name, which is entirely absent from the interior pages.

The realism extends to the art. Grell draws the cast as realistically proportioned people (with some allowance for occasionally suspect figurework), and there’s some impressive page and background designs. Lurene Haines is ambiguously credited for art assistance, with no further explanation, so the backgrounds may be her contribution. It’s also, with one glaring exception detailed below, emotionally strong art. You can see what the cast are feeling.

Even in pre-internet days one scene aroused considerable controversy. Midway through the plot Black Canary is abducted while working undercover and subjected to violent abuse, with rape hinted at. This occurs in prose and film thrillers, but the problem is the lack of subtlety about the presentation, which has an unpleasant voyeuristic quality, and it’s the one emotional lapse, with a leering villain, but a victim devoid of expression. The sequence is an undeniable blemish. In mitigation, Grell also mentions the disgraceful internment of all American citizens of Japanese descent during World War II, and is scathing about the liberties taken by the 1980s CIA in protecting American liberty. The passing of time has rendered this old news rather than contemporary politics, so the background revelations may lack appeal for a younger audience ignorant of the times.

Some people won’t be able to see the abuse scene as a misguided three page lapse in an otherwise decent thriller. It’s not an opinion to be discounted lightly, but does it invalidate the entire story?