Review by Tony Keen

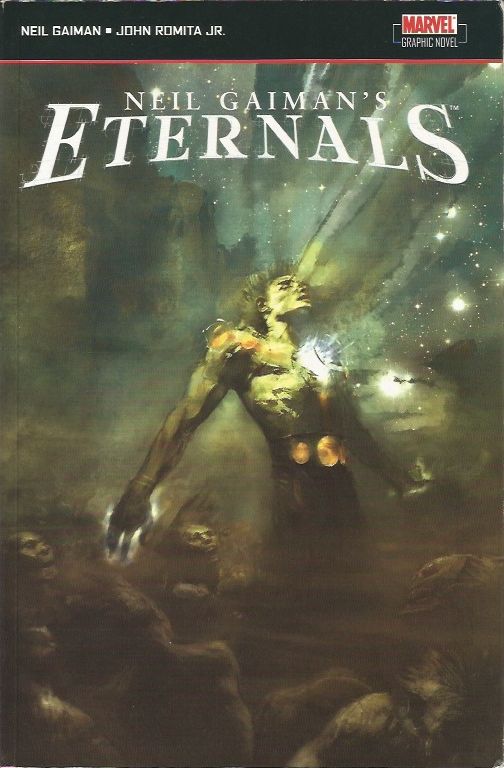

It’s a brave person or a foolish one who follows Jack Kirby, and this is doubly so when the characters are among Kirby’s later and more personal projects. Neil Gaiman’s take on Kirby’s Eternals, the story of a race of superior beings placed on Earth by cosmic entities called the Celestials, could fall into either category, but Gaiman has enough experience that he is probably best characterised as brave rather than foolish.

The main problem dogging the Eternals since Kirby’s run comes from corporate insistence on treating them as part of the Marvel Universe, where they don’t really belong. Kirby intended them to be outside the main Marvel continuity, imagining that in the Eternals’ universe their exploits inspired tales of mythological gods and heroes. In the Marvel Universe many of those mythological gods and heroes truly exist, so the Eternals must merely have been confused with the real gods in the past. This robs the concept of much of its power.

Gaiman doesn’t really solve this problem. The Eternals remain tied into Marvel continuity, Iron Man and Yellowjacket both appear in these comics and there are even references to the Civil War event running at the same time. Gaiman does try to put some distance between the Eternals and the rest of the Marvel Universe, in a similar fashion, if not as extreme, as the way he distanced Sandman from the rest of the DC Universe – the Eternals are superpowered beings, but they are not in conventional terms superheroes. With a few exceptions, at the beginning of the story no-one remembers the Eternals even existed, including almost all of the Eternals themselves. The narrative contained herein is about Ikaris, one of the few whose memory is partially intact, trying to gather some of his fellows in order to challenge a plot by the Eternals’ long-term enemies, the Deviants.

Gaiman’s Eternals are certainly not Kirby’s. The highlight of his writing is the way he manages to take ownership of the concept, whilst retaining echoes of the original. The same could be said of John Romita, Jr’s artwork. This is his mature style, when he was no longer trying to imitate his father. There are plenty of visual cues from Kirby, but there remains an individuality that belongs to Romita Jr.

Structurally, the story is not quite contained within the pages. Gaiman seems to deliberately set up matters for an ongoing series (which he would not write) that materialised a year later and is collected in Eternals: To Slay A God. That leaves too many loose threads at the end of this book.

Gaiman’s work is often praised simply because it’s Gaiman, but a case can be made that his superhero work is not his best comics writing. This particular example isn’t bad, but it is neither the best Eternals comic nor the best Gaiman work for comics.

UK readers can also purchase this as part of Hachette’s hardbound Ultimate Graphic Novels Collection partwork.