Review by Frank Plowright

It’s interesting that in 2002, with no hint of an Ant-Man movie on the horizon, that Marvel would choose to title this collection after Hank Pym’s diminutive identity rather than involving Giant-Man, whose experiences occupy well over half the page count. Perhaps it’s a matter of respect. As seen in the opening tale with an original publication date of January 1962, only the Fantastic Four pre-date Hank Pym’s début, although he only became a superhero later that year, by which time the Hulk, Thor and Spider-Man had all made it to print.

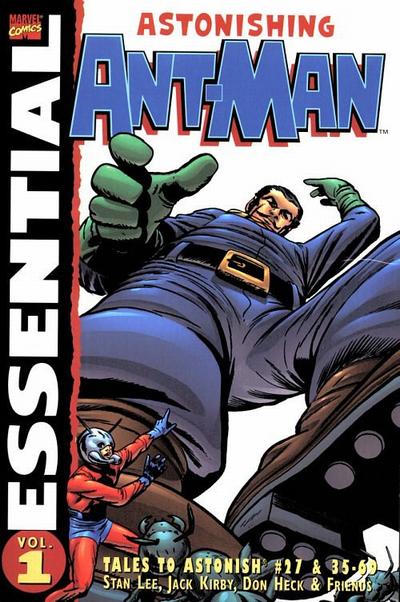

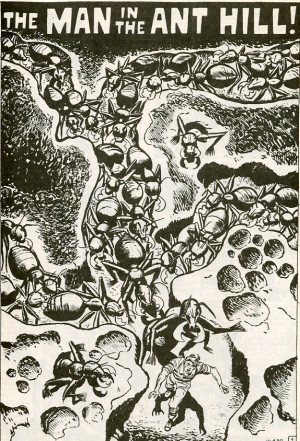

Other than providing a certain kitsch nostalgic glimpse into the past, it’s difficult to construct much in the way of justification for anyone curious to read Pym’s career as Ant-Man. He really was the runt of the litter, and hasn’t aged well, Jack Kirby’s brilliant splash page for his first appearance (featured art) notwithstanding. Kirby also blessed him with a costume, primarily that distinctive helmet with chin protector, that has emerged from the other side of hopelessly dated to retro-cool. Beyond that the plots, whether by Kirby, Stan Lee, Larry Lieber or Ernest Hart concentrate on communist era foes either wanting to steal America’s secrets or to subvert the glorious American way of life, or some of the most ridiculous villains you’ve ever seen. When Egghead, so named due to his distinctively shaped bald head, is the most effective of them it tells you everything. Yes, several received a post-ironic makeover in Nick Spencer’s 2015 Ant-Man series, but they’re a sorry bunch.

The Ant-Man feature improves for the appearance of the Wasp, as she has the basis of a character rather than someone who spouts dialogue. It’s a typical fawning woman of the era personality, but with a capricious lightness that manifests as the book continues to contrast Pym’s tinder dry character. Her first appearance is also notable for very nice art as Kirby’s inked by Don Heck.

That’s the same art team in place when Pym takes a step up by developing the capacity to become Giant Man. The difference in scale permits some more memorable art, but with the exception of the Human Top, the villains are no improvement. At least, with one exception, the communists have fallen by the wayside by this point, but so has any semblance of decent art with the more workmanlike pencils of Larry Lieber, Carl Burgos, Dick Ayres or Bob Powell sucking any joy from already ordinary plots.

Read en masse these early 1960s tales of Ant-Man and Giant-Man are a brain-sapping experience. The pervading feeling is that editor Stan Lee was occupied elsewhere, took his eye off the ball, and let the feature lapse into mediocrity. He returns to plot the final adventures, coming up with the interesting idea of Pym trapped at a height of 35 feet, which shows greater originality than almost everything other than the original creative process. It was too little, too late, and by 1965 the revived Sub-Mariner appeared a more commercial prospect and Giant-Man’s days were numbered. It would be the 21st century before either of the identities he created sustained anything other than guest star status, and Pym himself would become more popular as Yellowjacket.

Anyone just wanting to sample the material is better off with this bulky, but cheap, black and white paperback. For the really masochistic a pristine colour presentation in hardcover is available as two volumes of Marvel Masterworks. There’s also the more recent Epic Collection: Ant-Man/Giant-Man in paperback.