Review by Graham Johnstone

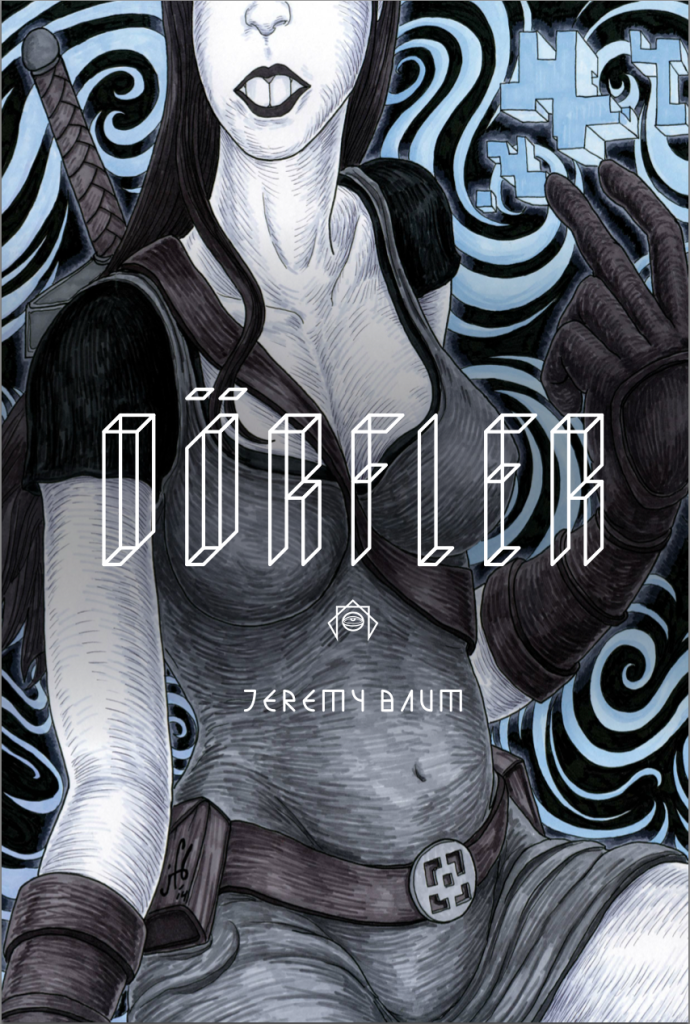

Dorfler is the first graphic novel by Jeremy Baum. It’s an eighty page, largely wordless book. and is also almost colourless except for touches of sky blue and blood red.

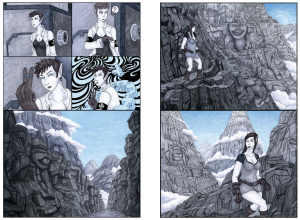

The protagonists are women. There seem to be three that we see in different roles and settings – dystopian city, rural idyll, and trippy mind-scape. Men are occasionally questers, and enablers, but mainly drones, agents of the dystopian system – in uniforms or white coats.

At times the women are flirtatious, coy-acting, and in what you might euphemistically call ‘pin-up’ poses. Are these all in a man’s imagination, their heroic aspects just spicing the fantasy? Or it may be some of this is a delusion caused by the mysterious headgear from the dystopian scenes.

Where there is text, it enhances matters, especially the discussions of memory, deja vu and dreams.

The publicity blurb compares Baum to ‘outsider artist’ Henry Darger, the reclusive janitor whose fantasy opus The Vivian Girls achieved posthumous cult status. It’s an intriguing comparison. Baum’s art also looks created well outside any art mainstream, and there’s the same sense of an obsessive forever accumulating their visions on paper. Darger’s drawings. though, channel the Victorian illustrations of his childhood, and subvert the prim source material with violence and hints of sexuality. The erotic elements in Baum’s work in contrast seem unconvincing, second-hand.

Some of Baum’s imagery and style – the elongated faces and hands – is rooted in the same period. Aubrey Beardsley, and the Aesthetic and Decadent art movements of the 19th Century, seem to have shaped this, but via the 1960s/70s revival, and influence on the the ‘hippy’ counter-culture. The trees and mountains recall Roger Dean, while the urban landscapes channel Vaughn Bodé and Moebius; the erotic scenes Jeff Jones’ Idyl. That’s quite a collection of 1970s stoner favourites.

The rendering combines technical pen outlines and grey marker modelling, each at odds with the other. Different media, say dip pens and washes would have been more in keeping with the trippy, dreamlike nature of the material. Occasionally, though, it comes together well, like in the landscape scenes on pages 12/13 and 58/59, where the greater level of detail in the line work hides the tell-tale marker ‘tide-marks’.

Baum’s personal vision is having to swim through a set of well used tropes – like he’s shuffled and dealt a pack of 1970s fantasy image cards. There are Pan-like creatures, pointed ‘elf’ ears, women with swords, floating jigsaw pieces, psychedelic swirls, insignia arm bands, cryptic symbols with eyes in them, women with ‘martian antennae’, and cute, but threatening anthropomorphised cartoon animals. For those that remember the era, it may lack the charming and distancing ‘patina’ of age – but for those too young it might serve as a kaleidoscopic look at a fascinatingly out of reach period and culture. There’s nothing to tell us if Baum himself remembers the 1970s, but maybe that’s best left mysterious.

There are several intriguing strands, and all the better for being only glimpsed, chopped up and shuffled. Despite the criticisms, Dorfler adds up to more than the sum of it’s parts. It begs several readings and flipping back and forward. This is a first book, and it’ll also be interesting to see what comes next.

There are a series of images at the end of the book by guest artists offering a great variety of styles and approaches, and some are very good.