Review by Frank Plowright

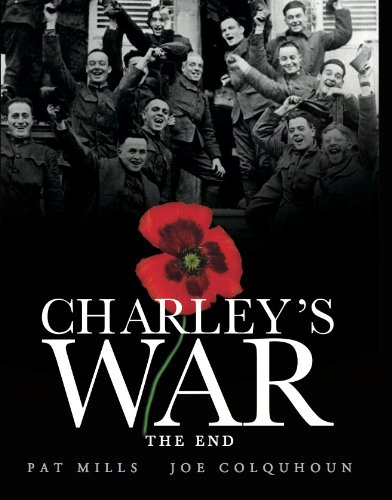

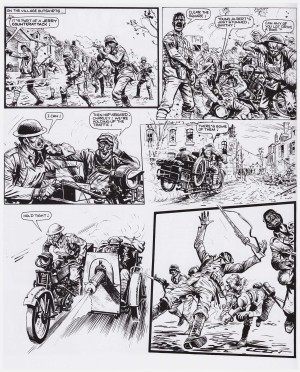

Joe Colquhoun occasionally incorporated genuine postcards, film posters or contemporary propaganda images into his art, and this final Charley’s War collection of his and Pat Mills’ collaborations begins the book with a beauty. It demonises the German soldier as a massive slavering ape in a stahlhelm carrying a giant club and abducting a helpless woman. It’s an image beautifully revisited in the final episode. As with Death From Above, there are more pages than not with access to Colquhoun’s original art, and the difference in reproduction between this and the early volumes is immense. It’s a treat to see every brush stroke and detail that doesn’t turn to mud.

As the book opens it’s the summer of 1918 and the massive casualties are beginning to take their toll on the ability of British forces to field an efficient army, so much so that the unhinged Captain Snell has been released back to the front lines after his stay in an asylum.

The previous Death From Above shifted emphasis to less extended narratives only covering a few episodes, but for The End Mills returns to letting the stories breathe a little so he can explore different angles. Most of the early pages are Charley’s experiences in a prisoner of war camp, followed by a sequence detailing the end of World War I. This is spliced with a showdown between Charley and Captain Snell, melodramatic, but suspenseful.

Mills then shifts the action to Russia where British troops supported the Czarist regime against the Communist rebellion, many without knowing why any more than they knew the truth of their consignment to the trenches. It’s an era brushed under the carpet as far as British history is concerned, and the feeling here is more of the traditional boys adventure strip, but there are some great sequences. The best of them involves an armoured train, which on re-reading for his accompanying notes Mills likened to steampunk SF.

Beyond Charley Bourne, Mills created several memorable characters for the series, many of whom don’t survive. One who does is Sergeant-Major Tozer, a paragon of bullish authority bearing a waxed moustache you could pick locks with and perpetually at boiling point. Despite his ranting manner Mills identifies that Tozer cares for his charges, and it’s only fitting that the book’s beautifully composed final scene is between Tozer and Charley in 1933.

After over six years writing the feature, Mills quit Charley’s War when refused a research budget to enable stories set in World War II to have a similar tone to those he’d already written. Colquhoun continued to illustrate Scott Goodall’s more conventional war stories about a now wiser Charley, and these only remain available in the original editions of Battle.

Charley’s War is a series whose reputation increases year by year, and recent attention focussed on centenaries of numerous events from World War I have fed into this. It’s an extremely rare person who can genuinely claim to have influenced a generation and their children in the manner Mills has. As a creative maverick with entrenched ideas of social equality his strips have been sugar-coated subversion, eating away at the establishment’s underlay. Have the creators of Battlefield 1 seen Charley’s War? You’d like to think so.