Review by Graham Johnstone

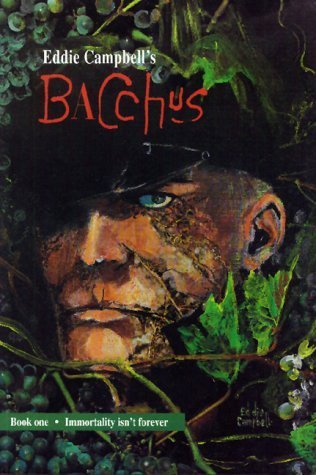

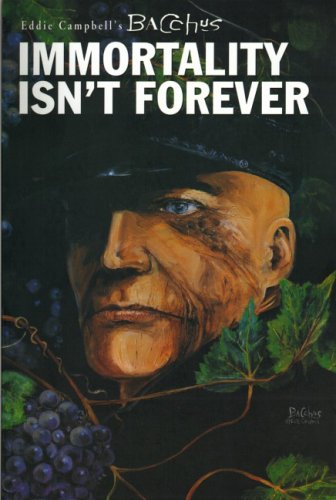

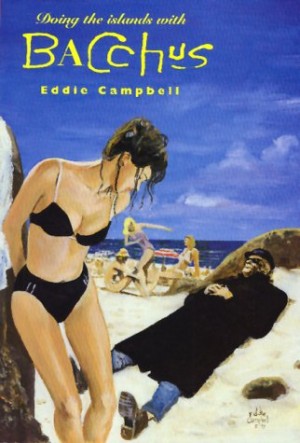

This is the first volume of Eddie Campbell’s collected stories about Bacchus from Greco-Roman mythology, the god of wine, “ritual madness” and revelry – partying, in 21st century terms.

When originally published in the late 1980s these stories seemed at first, a strange change of direction for Campbell – from slice of life stories to epic myths. In fact it wasn’t such a volte face as it seemed. Alec, like Bacchus, was a lover of wine, women, and song, and a raconteur – spinning tales of ‘epic’ parties, alluring ‘goddesses’, betrayal, revenge, and so on. In both cases they foreground the art of telling the story. Also, at least in these early stories, Bacchus operated in the present.

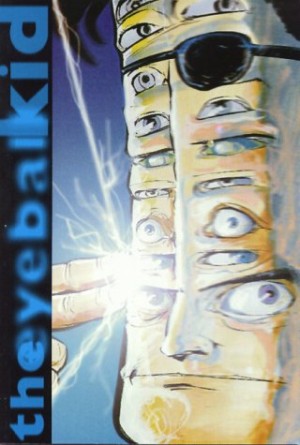

It’s not just the story of Bacchus, but also of various other characters spun out of Greco-Roman mythology: in this volume mostly, ‘Joe’ Theseus (slayer of the tragic Minotaur), and ‘The Eyeball Kid’. (grandson of hundred eyed giant Argus ‘all eyes’), unlikely possessor of much of the power of the dead gods.

As the title Immortality isn’t Forever suggests, Campbell’s take is that these guys realise they aren’t going to last forever, and as the book starts they are deciding that it’s time to settle any unfinished business. Theseus gets wind that Bacchus is coming for him, and heads off into the sun. The Eyeball Kid is also looking for him, for his own reasons. God’s and demigods they may be, but they’re still acting out familiar routines. Theseus holds a fatal attraction for women. The Kid has an Olympian guilt complex.

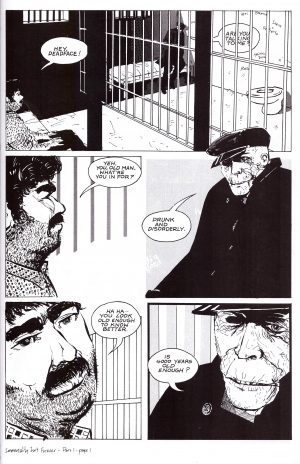

Campbell sensibly starts with the present drama, and gradually fills in the ancient back-story through tales told to entertain hosts and companions. He has fun with it, particularly how they negotiate the modern world. The mighty have fallen, but in appropriate ways. Bacchus we met in the drunk tank, and he’s reliant on others buying the drinks. Theseus, appears a gang boss, but leaves it all behind to flee for his life. Yes, Theseus thought to be secretly the son of Poseidon, God of the sea, flies overseas, and ends up cleaning swimming pools.

Campbell’s a long-time scholar of the comics form: time, motion, panel transitions and so on, and he puts his repertoire to good use here. There’s a nice transition between Bacchus and his cronies partaking of ambrosia, food of the gods (here psychotropic mushrooms) and Theseus opening sandwiches and a can in an airport.

On Alec, Campbell pioneered the use of self-adhesive grey tones, in a loose, painterly fashion, that like Monet and the Impressionist painters, still hung together with an almost photographic realism. He uses that technique here for the present-day scenes, but moves from technical pen to loose brushes for line work. He experiments with the rendering. There are some quite brilliant panels, and several that look poor. Campbell’s pursuing spontaneity and a sense of urgency here, so the weaker panels seem just part of the deal.

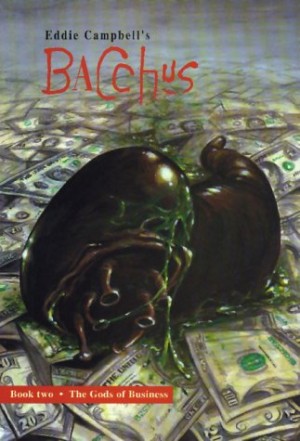

The original myths are brilliant stories to start with, and Campbell brings them vividly into the present. This should appeal to anyone that likes a good story, as well as more literary readers and ink drawing connoisseurs. The raconteur continues with The Gods of Business.