Review by Ian Keogh

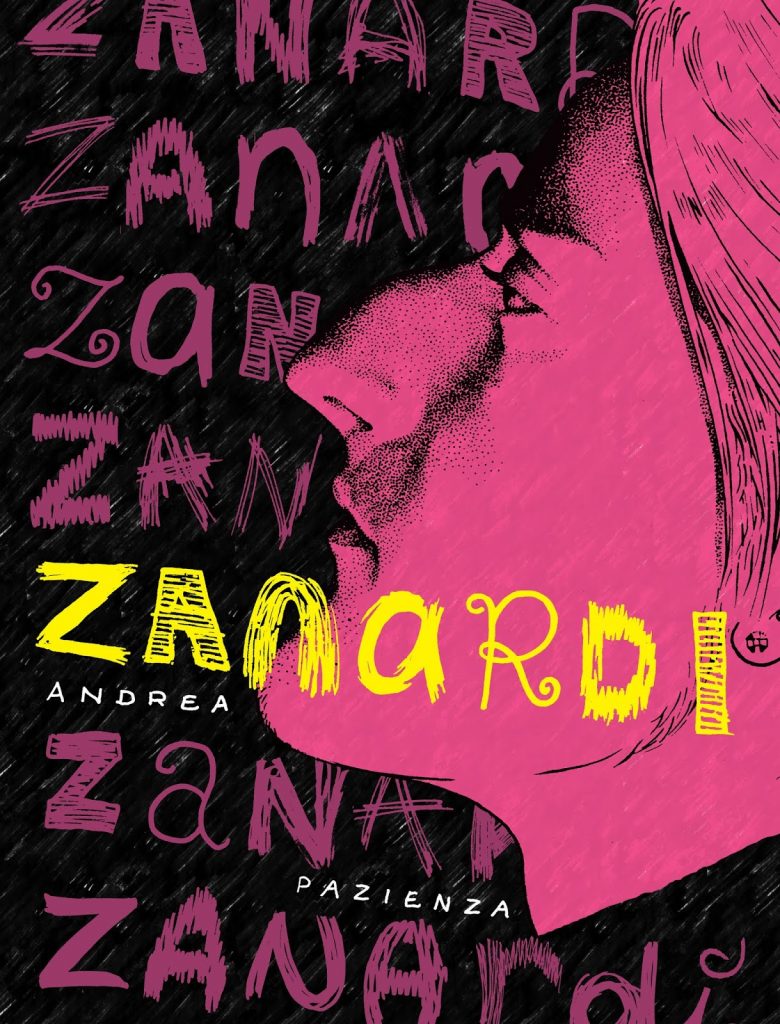

Zanardi is a troublesome collection to review, prompting conflicting thoughts. Andrea Pazienza is a creator all but unknown to English language readers despite the vast respect he’s accorded in his Italian homeland, a respect diligently documented by noted critic Emanuele Trevi in his introductory analysis. Pazienza was hugely influenced by American underground comics, yet astute enough from the beginning to combine his own inspiration with those influences instead of just recycling. Almost his entire comics output centred around the exploits of louche overage high school student Zanardi and his friends, Colasanti and Petrilli, all-purpose iconoclasts who never move from the brief period of the late 1970s and early 1980s when Pazienza began their stories.

Zanardi himself with his aqualine nose can resemble Uderzo’s Julius Caesar from the Asterix books, especially in the uncompleted last story, and he’s the constantly provocative starting point for a selection of amoral farces. These aren’t always the works of the genius Trevi’s glowing contextualisation may lead readers to expect. Some are novel, others ordinary, but the consistent wonder is the art.

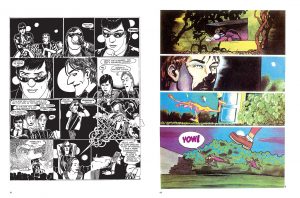

Pazienza was an exceptionally restless artist, even early pages (sample left) showing wild deviations into different techniques within the same story, and flights of fancy as he switches between naturalistic bright colour and exaggerated black and white cartooning. Some art is crude, or sketchy and plastered with dialogue as if Pazienza’s hurrying through scenes he doesn’t want to draw to arrive at those he does. Other pages are monumental works of art, delicately stippled black and white, or frenetic cartooning, this influenced by Gilbert Shelton, while he also loves the ornamentation of Rick Griffin. The constantly morphing art keeps Pazienza fascinating despite the disturbing turns his stories take.

Until getting used to Pazienza’s methods, following his strips can be difficult. His tales switch the narrative back and forth through time without any distinct indications, and over the course of his entire Zanardi works there is little concern for internal continuity even when it’s obvious one story is set later than others. If someone dies, they die, but if they’re needed for a later piece, back they come. This isn’t intended to proclaim Pazienza as a difficult creator to appreciate. He’s not, it’s just that certain conventions have to be laid to one side. Laying moral judgement to one side is more difficult, because there’s an elephant in the room. Whether or not the amoral and hedonistic Zanardi is Pazienza’s wish-fulfilment alter-ego is for the knowledgeable to discuss, but he lives a no-consequence life of violence, rape and intimidation. The incidents occur within generally funny stories, but in themselves are far from amusing, and likely to offend, particularly the weaponising of rape. With all that already on the account sheet, the misogyny is just a misdemeanour.

While the opportunity to see Pazienza’s work in English is welcome, and the art at its best astounding, the years may have rendered some content too offensive for today’s tastes.