Review by Frank Plowright

Throughout her 1950s and 1960s childhood Carol Tyler would see objects around the family home connected with her father’s World War II service in Europe. These were all off limits, and he’d fob off any questions about his service. A photo album from the period portrayed a man smiling and happy in army uniform, which was a contrast to the perpetual grouch she grew up with. Tyler knew her parents met in the early 1940s, but very little more about her father’s wartime circumstances.

Fast forward to 2001 with Tyler living hundreds of miles away from the parental home. Her first reaction is that something’s wrong when her father phones, as that’s so unusual, but instead the dam has burst and he spends two hours talking about his wartime experiences. Astonished at the sudden revelations Tyler arranges to video his recollections. In addition to the purge being necessary for Chuck Tyler, the results are a lifeline for her, as her husband of many years has just left. Concentrating on a project to create a family scrapbook enables her to suppress much of her own trauma.

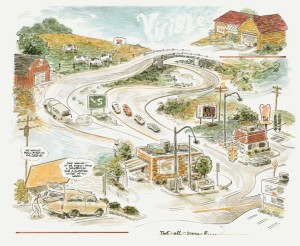

His experiences are presented as a block of hand-written text and accompanying illustration, each numbered as if an ordered collection of trading cards. These are interspersed with anecdotes from his youth, recollections from Carol’s youth, and her 21st century emotional struggles living with her daughter. When her relationship broke up she could no longer afford to live in California and chose her new Ohio hometown by sticking a pin in a map.

To consider the raw emotional turmoil presented here charming may seem somewhat patronising, yet charm is a definite artistic choice displayed in Tyler’s decorative cartooning and the intentional scrapbook memoir design. She begins with pen portraits of the recurring cast, noting their later visual aspects, introduces symbolism early, and there’s a whimsical element to her cartooning, with art extended over panel borders. The borders themselves on occasion play a part, once serving as a metaphor for hitting rock bottom as she crashes through them to land at her father’s feet.

Tyler is a fascinating cartoonist. On the surface everything appears almost simplistic, and her figures are often sketchy, yet they carry a deep emotional complexity. The book may also appear jumbled when flicked through, but this conceals both inventive narrative solutions and the scrapbook approach not apparent until A Good and Decent Man is read.

Honesty is an essential component here, with Tyler as harsh on herself as she is on her father, although perhaps a little too love-blinded by her partner Justin. While not explicitly referred to, there are indications that post-split Tyler endured a period of considerable deprivation. The subtitle, though, is puzzling. Soldier’s Heart reveals it originating with one of her father’s former comrades, but given later revelations is it intended as sarcastic?

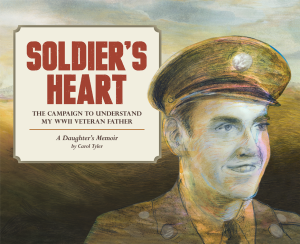

As this memoir extends over three volumes, compiled in 2015 as Soldier’s Heart, there’s no sense of closure here, and it may be the case that the overall title is a deliberate reference to this. As presented, Chuck appears very much a man of his generation rather than someone particularly shaped by his wartime experiences, although there is a period in Italy about which he’s not forthcoming, and the final pages display the volcano that has been uncorked.

To this point there’s nothing particularly remarkable about Chuck Tyler’s period of service, but the loving manner in which it’s presented, and the complex wrapping create several compulsive portraits. The story continues in You’ll Never Know: Collateral Damage.