Review by Ian Keogh

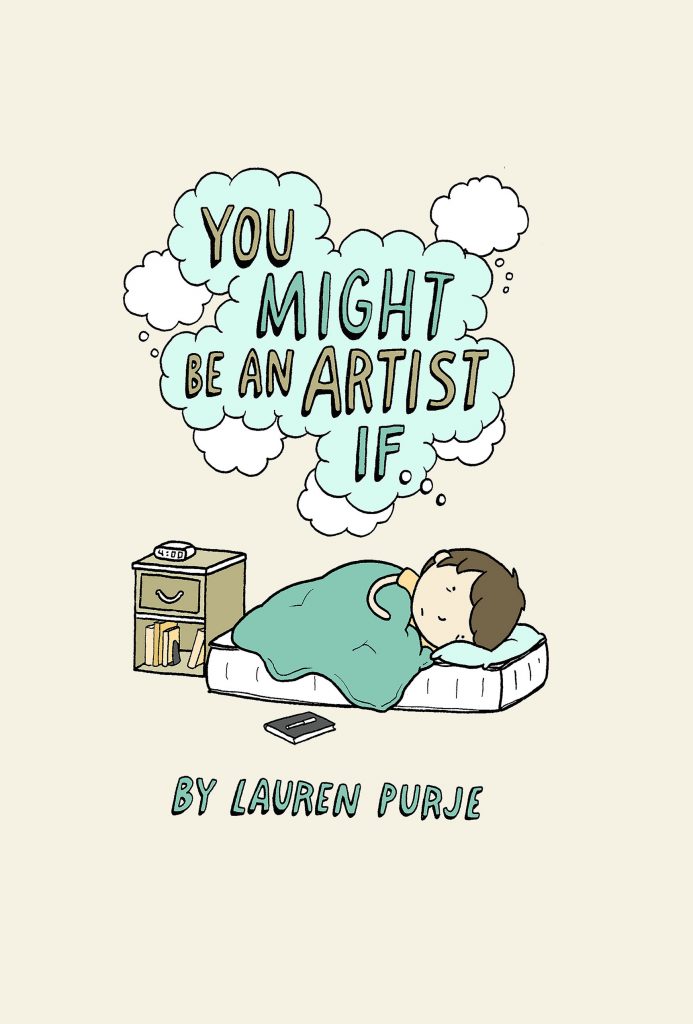

Observational humour is the comedian’s staple these days. No-one tells jokes any more, and that’s very much filtered through into printed humour also. Millions of people around the world loved Love Is… cartoons in the 1970s and 1980s, in which cute characters were accompanied by an often obvious statement. Critics heap scorn on Dilbert or Cathy for being poorly drawn and nailing the lowest common denominator in any given situation, yet the strips have massive followings. Garfield has prompted an industry of tie-ins and the creation of associated merchandise surely keeps thousands employed. This is all by means of noting that the most obvious and hollow comments can be received as pearls of wisdom. Lauren Purje’s website notes that the first printing of You Might Be an Artist if… sold out, which indicates some appeal.

The book contains several potshots at the assumptions of critics in defining someone’s work and the assumptions they might have concerning what constitutes art or humour. There’s no consideration that the work might be open to definition unconsidered by the creator. These are accompanied by far more strips detailing procrastination, self-pity, self-doubt, and more procrastination, with several taking the Greek myth of Sisyphus perpetually rolling a rock up a hill as a metaphor. They combine to present a vacillation between ego and insecurity, that rather than raising a smile engenders a concern about Purje’s well being, and that she has some form of safety net. There’s a repeated message that any art has to fulfil the artist and while every single strip might come from the heart, barely any manage an original observation. Those that do really leap out. One draws a parallel between the effects of experimentation isolating mice and their resulting lack of ease in subsequent social situations with the life of an artist and their personality. Another speculates about whether boredom is greater now than it was in the pre-internet age or if it’s age-related. Unfortunately, such strips are very much the minority.

The overall looseness to the cartooning and conversational tone isn’t that far removed from Keith Knight, but he’s friendly and engaging, eyes open to the world and its opportunities, and welcoming to readers, while Purje is enclosed, employing a narrow theme as self-assessment. The same ground is relentlessly trodden, yet rarely offering insight into feelings experienced by everyone on occasion. In bulk it’s repetitive and off-putting. As a few cartoons hit the spot, perhaps more time spent on quality control would avoid the repetition. Purje’s back cover copy states we should consider the collection as her cry for help, and after reading the statement echoes not as wit, but as genuine.