Review by Frank Plowright

English language comics has never seen anything like Yvan Alagbé’s Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures. It’s an astonishing series of seven pieces, intimate and provocative, non-judgemental and heartbreaking, drawn in various styles ranging from sketched naturalism to abstractions, the storytelling as varied as the art.

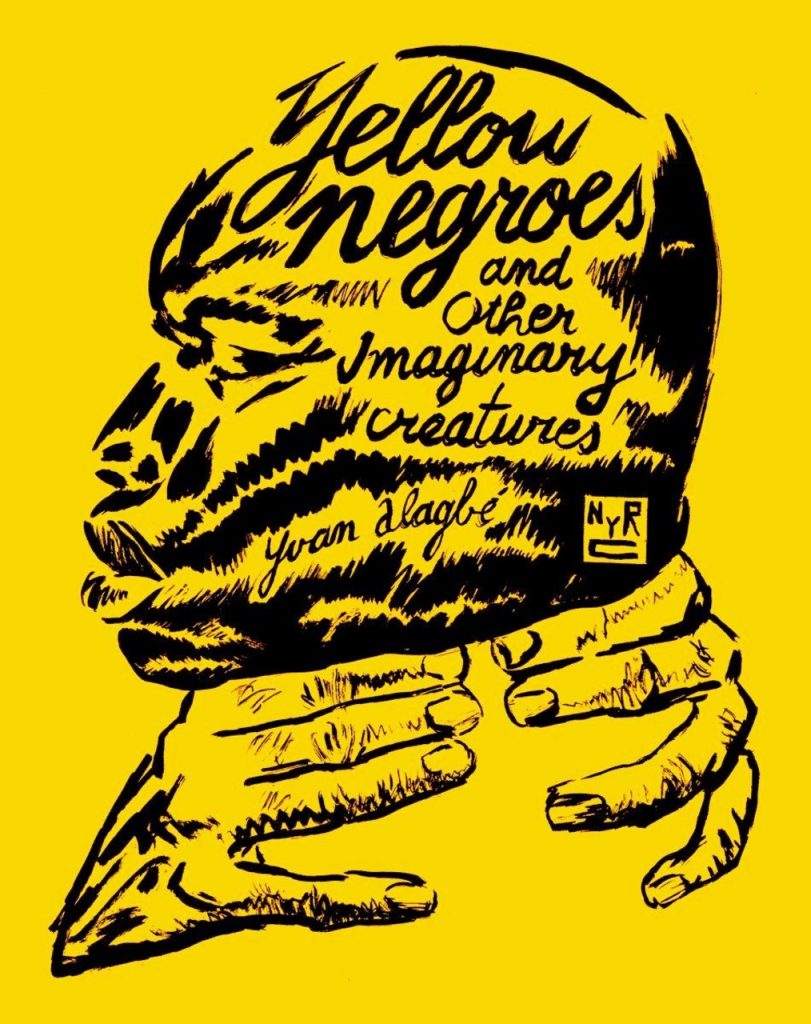

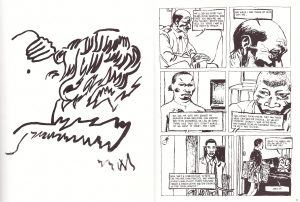

An attention-grabbing cover showing a pair of hands around an African’s neck represents the content within, shocking and demanding attention, immediately asking questions. So does ‘Love’, the short opening piece beginning with the illustration forming the left of the sample pages. A further three pages pull the viewpoint out further via a series of what seem to be rapidly produced sketches from a life drawing class to set the tone for what follows.

The title piece is a sweltering meditation on loneliness, despair, guilt and cultural identity set in France during the 1990s and following two primary characters. African artist Alain is conflicted and angry, but to all intents settled with a French girlfriend. He’s befriended by Mario, a policeman who worked for the French as they repressed Algerian immigrants in France supporting the revolt against the French in their country of birth during the early 1960s. Mario is also of Algerian descent. Now retired and widowed, he lives with his infirm mother, and on a subconscious level guilt about his past is seeping out. He’s pitiful and needy, offering the hand of friendship to assuage his own guilt and loneliness over 46 pages of seat-squirming awkwardness. The subtext is that he’s what the French once considered a worthwhile immigrant, yet as they seek to sweep their colonial days under the carpet he’s an embarrassment, while Alain, a refugee without papers personifies the African immigrant so much of Europe considers undesirable. He’s not any saint either, not above exploitation. It’s an exceptional and disturbing piece that sticks in the mind.

Alagbé returns to secondary cast member, Alain’s sister Martine in the following story. We learn second hand of how she formed an ill-advised relationship on arriving in France. The African taxi driving narrator is depressed and maybe unhinged in what’s a challenging piece that’s ultimately not as rewarding as the title strip. That’s followed by ‘The Suitcase’, a deliberate triviality, possibly designed to burst the bubble of intellectual weight imposed on Alagbé in France after ‘Yellow Negroes’ was first published in 1994.

Two short pieces comment on France’s uneasy relationship with people on whose ancestors they imposed their language. Alagbé briefly included his stand-in in ‘Yellow Negroes’, but narrates these directly. He perpetuates the memory of Benin revolutionary Thomas Sankara, and via series of street scenes set around a Parisian intersection relates how in 2009 Malian immigrants occupied an employment agency. For anyone not sharing Alagbé’s knowledge both prompt further research, as intended, but beyond the impressive illustration they don’t resonate. A symbolic final strip considers some of the earlier work, and also Alagbé’s own cultural identity, born in France, but sharing the immigrant experience after spending three years of his youth in Africa.

The title story is five star material, but it also instils an expectation not met by most of the remaining strips. With their fine art sensibilities they’re all interesting to look at, but don’t have the intensity or instant connection. That noted, ‘Yellow Negroes’ is worth the purchase price alone.