Review by Ian Keogh

Wonder Woman was created by respected psychologist William Moulton Marston, his reputation presumably preventing any questioning of the strange and sexualised ideas he introduced to the feature. Over the previous volumes of Earth One Grant Morrison has probably been the first modern day creator to extrapolate those ideas. From today’s perspective the idea of male subjugation is a selective fantasy rather than a desirable ideal as it seems to have been for Marston, and mind alteration ensuring alignment to an ideal is considered abuse. Yet Morrison takes those and other ideas at face value, as espoused by facets of Amazonian society and shows how they might work out applied to wider humanity.

Morrison’s at his best when given a broad canvas to supply his ideas, and having built his interpretation of Wonder Woman and her world over the previous two volumes, it flourishes in this conclusion. The opening pages make it clear we’re looking back at the events immediately following Volume Two from a thousand years in the future, when Amazonian values have been applied as humans colonised the galaxy. Morrison’s been gifted the divisive American political climate that’s become ever more fractious as the volumes of Earth One were issued, and can now relate anyone opposing the peaceful ideas of the Amazons to the current US elite. They’re represented by a gung-ho Maxwell Lord and military cronies, and while some will guess beforehand, Morrison doesn’t consider the revelation of who Lord really is to be a secret worth keeping. He, and other men, lapse too far into caricature to be anything other than figures of ridicule, and that’s a shortcoming.

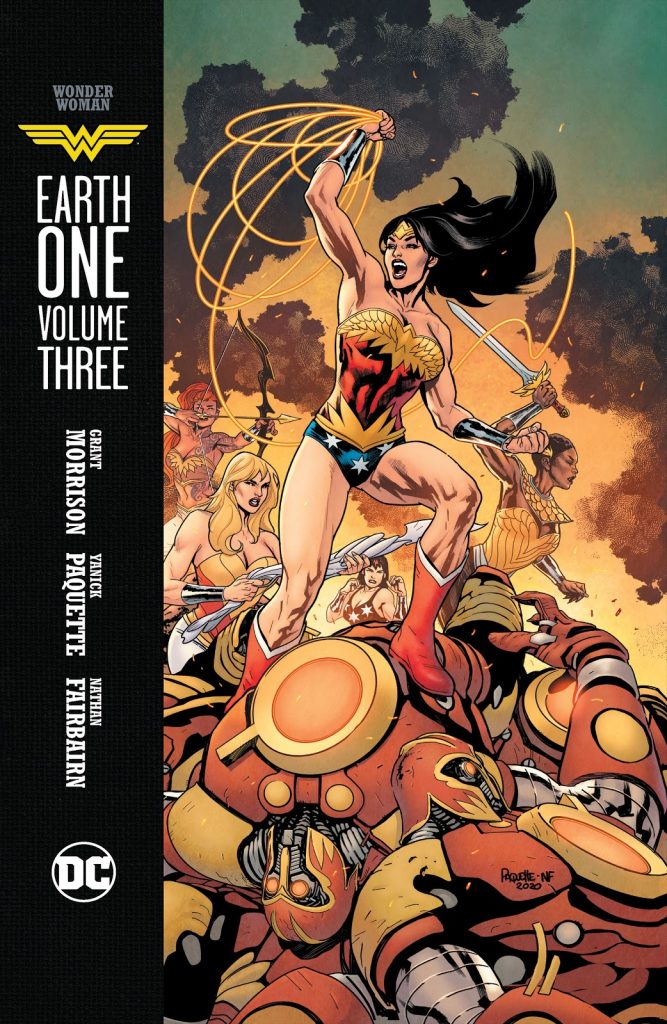

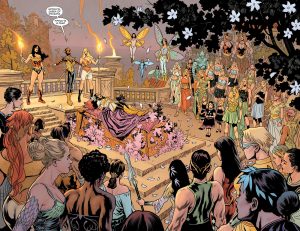

From the start Yanick Paquette has taken a decorative approach to the art, which sometimes results in a sugar coated pill. Here he defines several different Amazonian societies, each of them distinct, and differing from the society we’ve seen in previous books. That’s just his starting point, and he provides beauty throughout. Perhaps by glamorising the Amazons Paquette’s undermining an idea of inclusion, as we only ever see perfection, but anyone who can’t admire the work and imaginative designs is denying themselves.

The storytelling straddles a clever line of nostalgia in being pared down to essentials, yet being modern via much being reduced to sloganeering and online messages. As on other projects, Morrison throws away concepts others would use to build entire stories, one being a recasting of the underworld in terms of bandwidth, a compelling and interesting idea, yet just a passing notion here. It also features an idealism and optimism not always associated with Morrison. Is he mellowing with age? Although flawed, this conclusion is bold, entertaining and the best volume of the series.