Review by Frank Plowright

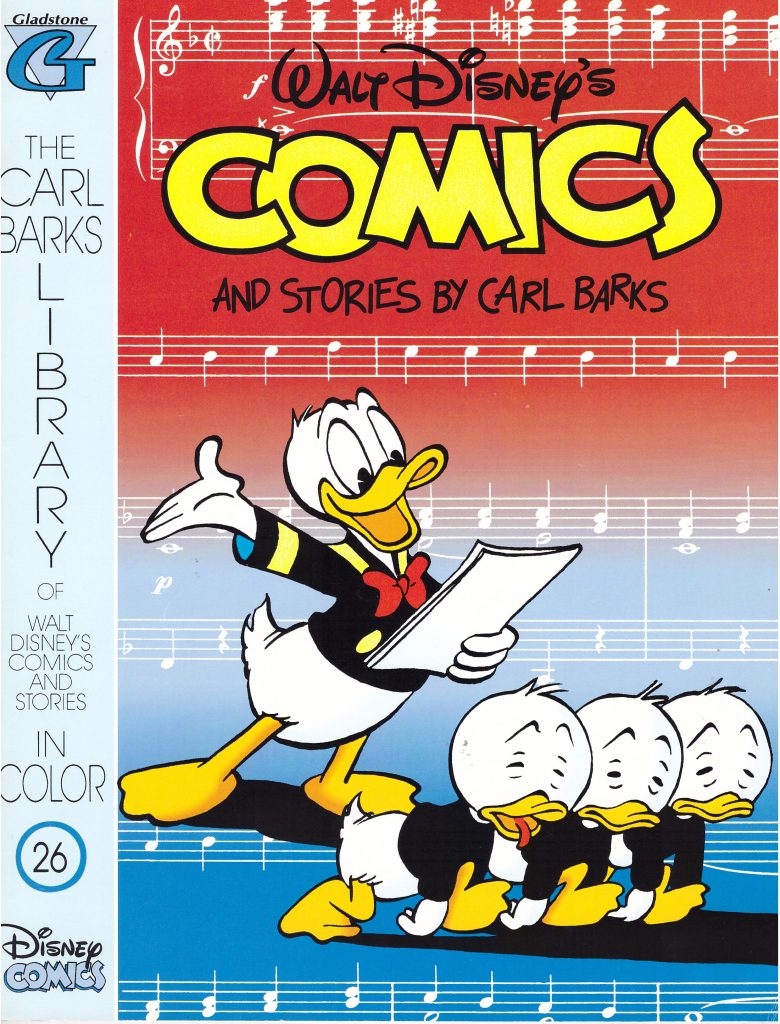

Carl Barks is one of the greatest storytellers ever to work in comics, and in 1954 he was at his peak. Each of these five stories is perfectly plotted, hinging on characteristics we know Donald Duck has. There’s no full bore volcanic temper tantrum like he used to have, even when sorely provoked, but all other moods are there. There’s his incompetence, his lack of ambition (except when it comes to wanting to better his supernaturally lucky cousin Gladstone Gander), and his tendency to take a joke too far. On the positive side we also see his tenacity, his good nature, and his desire to do the best for Huey, Dewey and Louie, even if that means chasing them halfway around the district to ensure they attend school.

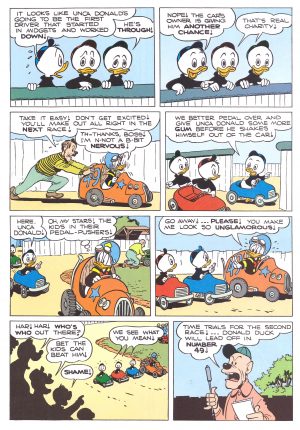

That story provides a masterclass in how to sustain tension and comedy. Barks arranged the material for Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories to coincide with the seasons and holidays of the year. So, allowing for the cover date on a comic being later than the month it actually went on sale (to extend shelf life), the October 1954 issue appeared as children throughout the USA were preparing to return to school. Huey, Dewey and Louie have other plans, and we see them plotting to avoid it. Donald, however, is wise to their tricks, and outwits them at every turn, until he’s eventually so clever he outwits himself. Barks applies his moral code, and at the point where Donald takes the joke too far it’s inevitable there’ll be some retribution. The jokes are good, the cartooning is wonderful and the topic surely as relevant today as it was in 1954.

A minor, but memorable reason Barks’ stories stand out is that his eccentricity sometimes slips through. The boys adopt a chipmunk and call it Cheltenham. At one point Donald is employed as the delivery boy at the Skunk Oil factory. Barks squeezes grown men into mini-race cars for a preposterous image, and the ultimate device he creates for Donald’s escalating musical experiments is hilarious. These are small items in the course of the larger story, but embed those stories in the memory.

The dialogue given to a native American in the fishing story is pure 1930s Hollywood, and so possibly offensive today, a thoughtless caricature. However, balanced against that is that he’s serene and knowledgable, the smartest character in the story. Barks didn’t set out to offend, but was of his era. As we all are.

This paperback book is long out of print, and the stories are now best located The Ghost Sheriff of Last Gasp, part of the Fantagraphics hardcover series reprinting Barks’s entire works.