Review by Ian Keogh

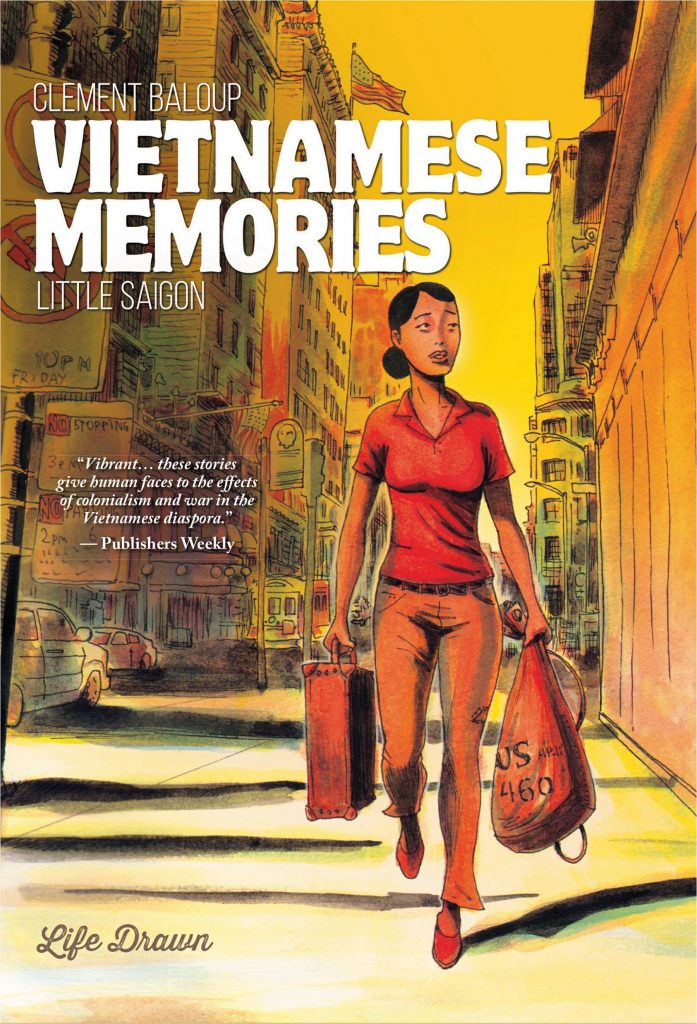

Clément Baloup grew up in France with a Vietnamese father who never spoke about his past until a chance conversation when cooking a meal one night. This was a revelation to Baloup, who knew little of Vietnam’s history, nor occupation, and the conversation led to him interviewing other Vietnamese immigrants to France, resulting in the first Vietnamese Memories. Little Saigon follows roughly the same pattern, but instead interviewing Vietnamese immigrants to the USA.

The title is that applied to Vietnamese communities in American cities in a casually derogatory manner, but seemingly embraced by people who’ve left their homeland within memory of what’s known as Saigon in the USA being renamed Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam.

Sadly, the first Vietnam Memories failed to exhaust variations of inhumanity during and after the Vietnamese war, as interviews with residents of San Francisco, Los Angeles and Charleston confirm. In each Laloup also briefly investigates the experiences of people from other Asian nations who’ve immigrated, the Japanese internment camps of World War II and Laoatian gangs observed in passing. Also noted is the transformative effects of shopping malls in violent areas.

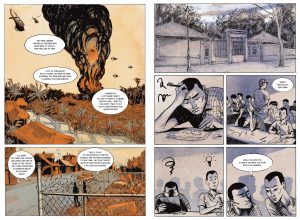

There’s a delicacy to Baloup’s evocative documentation, letting people relate their experiences in the first person and avoiding any deliberate sensationalising of what are already three disturbing stories. Anh talks about her experiences in refugee staging posts in Malaysia and Indonesia, her beauty so envied by others proving a curse to her at seventeen. Yên’s desire to escape instead lands her to the greater confinement of prison, and Tam and Nicole’s love appears doomed by her gang-leading brother. That last recollection begins as somewhat the relief. While Nicole’s life wasn’t easy and hardships were suffered, for much of her narrative she’s untouched by violence and oppression. Contrasting the other experiences, getting to the USA is comparatively simple, and it’s once she’s a citizen that problems begin, Nicole ending up cursed by demons and depression.

Baloup still varies his art, colours separating present from past, but not to the degree of the first volume, discarding the watercolour painting to stick with line art. What he hears requires compassionate depictions and the people shine through, whether as oppressors, friends or victims, all drawn wonderfully.

Bookending the major recollections are conversations with two Vietnamese restaurant owners, continuing the theme of food from the first book. Based in New York and New Orleans, they have different views on life and cuisine, but they are charming, honest and informative. That’s the bottom line for both volumes of Vietnamese Memories, where resilience is a key unifying factor between people who’ve endured horrific and horrifying experiences that most have come to terms with and moved on. It’s surely impossible to read what they’ve been through without feeling for them and admiring how they’ve coped. Would we?

Baloup continued his series five years later detailing the experiences of Taiwanese refugees, as yet unavailable in English.