Review by Karl Verhoven

There’s an excellent beating heart pulsing beneath Steve Orlando’s story, that of disenchantment with our current political systems. The story may be set under the sea in Atlantis, and the primary concern is a science fiction adventure, but every aspect of that is informed by social commentary.

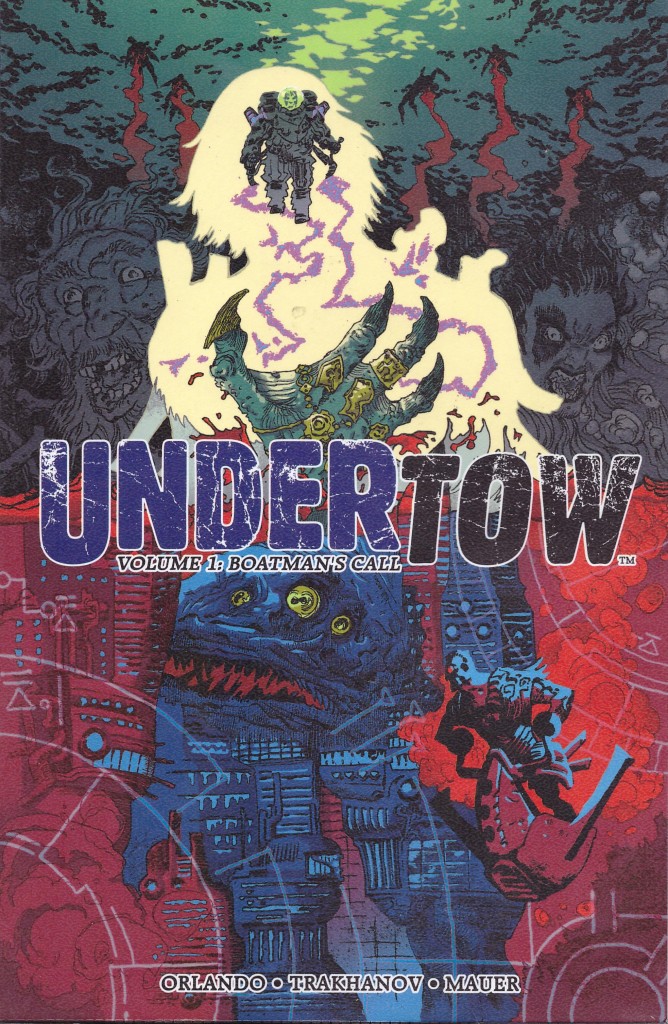

Orlando and artist Artyom Trakhanov’s Atlantis isn’t the mysterious and unknown sunken city luring cartographers and treasure hunters, but a vibrant, corrupt and technologically advanced society keeping a watchful eye on surface humans just learning to create basic hunting tools. The city administration prioritises the contentment of the wealthy and aspirant while ignoring a disadvantaged underclass. The ruling party trade in constant deceit, and have demonised one Redum Anshargal, characterising him as enslaving hostages to perpetuate a rebellion, and Undertow is his story as seen by the previously privileged Ukinnu Alal.

Anshargal is a complex creation, willing change through force of an indomitable personality. He and the crew he maintains are at the forefront of scientific development, and a major aim is discovering a method of colonising the surface world, Atlanteans being prisoners of their gills. Isolating rumours of an amphibian being takes him away from his community, and a restlessness ensues.

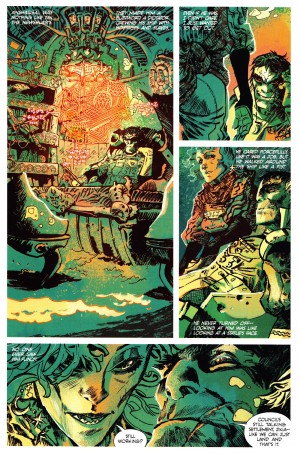

Trakhanov’s art conflicts. He creates an intensely coloured undersea world, yet one that distracts via extraneous detail, the eye not always drawn to the crucial image, which is often the case in combat layouts. When it works, however, it’s spectacular with some feral scenes and a consistent sketched looseness to the main cast, which defines their personalities well. The use of colour is also variable. For much of the book it’s well considered and on occasion memorable, but there are also pages of vivid clashing shades.

Everything is set up well over the opening chapters. There are big and impassioned ideas, but the necessity of contracting them for a story results in drawbacks. Orlando wants to show how discontent festers, but after what he’s set up that it festers so soon after Anshargal leaving on a mission is improbable. The extension to ensure a longer absence is then a distraction, a spectacle in places, but a contrivance showcasing a preening narcissist: “The dry places are mine. All beasts live and die for me, as unto a God!”. He’s tiresome, and lacks credibility as an intelligent being who ought to crave conversation. By the time the story’s back on track its too late. It draws to a rapid conclusion with so much left unexplored. This is labelled as volume one, but it’s all there is and the main feature ends with a whimper.

A selection of short stories by assorted writers and artists close the book. These are more ethereal than politically driven, but none essential, and one very poorly drawn. Yuri Astapeev, however, is notable, an artist with a distinctive sense of layout and colour coupled with over-rendered figures.

Sadly, Undertow is a graphic novel of ambition and potential unrealised, but squandered from within. A little more in the way of gentle introduction before moving to the bigger issues would have served it well.