Review by Ian Keogh

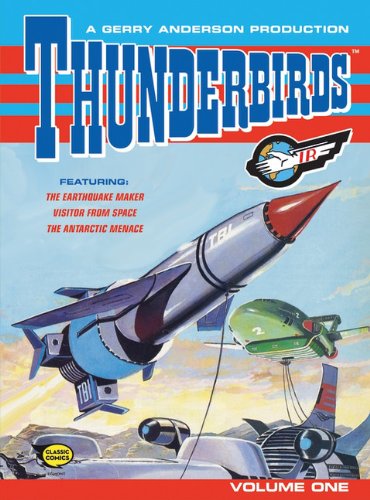

Gerry Anderson was immaculately attuned to the British optimism of the mid-1960s when he created Thunderbirds. The idea of a futuristic adventure and rescue squad with fantastic craft painted a picture of a glorious future one hundred years later where global peace was rarely threatened other than by natural disasters.

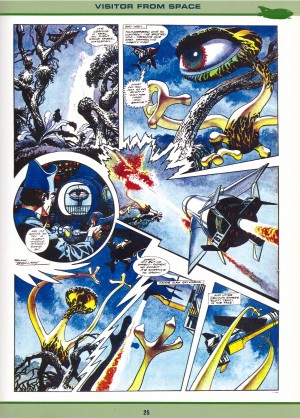

Who better to illustrate this near utopian vision than Frank Bellamy, in 1966 Britain’s finest comic artist in a strong field. Unlike the TV show, the scenes were only limited by Bellamy’s imagination, not by budget, and his imagination was immense. He accentuated the wonder of the Thunderbirds rescue craft, frequently depicting them as seen from below, so highlighting their distance, and providing a sense of disorientation among the chaos of rescue missions by never using traditional straight lines to separate panels. He also humanised the frankly rather freakish looking TV show puppets, but created equally freakish foes, such as the giant alien eye on legs with a glance that transforms living tissue to stone.

In crediting only Bellamy the impression is given that he also wrote the stories, which isn’t the case. Scott Goodall is responsible for ‘The Earthquake Makers’ and Alan Fennell for the remaining two strips. They’re all aimed at thrilling young boys, with no thought that adults would be poring over them fifty years later, and they stand the test of time as entertainment for youngsters, but the wonder is all in the art. Goodall and Fennell needed to begin each weekly two page instalment with the conclusion to the previous week’s cliffhanger, then if they’d been efficient, they might have ten further panels to move the story forward and set up the next cliffhanger. It means the stories move at the frenetic pace of the previous generation’s adventure reel films that inspired them, preventing too much thought, for instance, being given to the viability or desirability of constructing an army of robot penguins.

This is the first of five volumes each presenting three complete stories. They’re brief, the longest running to sixteen pages, and the thick paper stock bulks the book considerably. It really has no bearing as there are no continuity elements, but for those who care, despite this being volume one, these aren’t the earliest Thunderbirds stories produced. Anyone wanting a thorough immersion can find this content along with the remainder of Bellamy’s material and some stories illustrated by others in Thunderbirds: the Complete Collection.