Review by Karl Verhoven

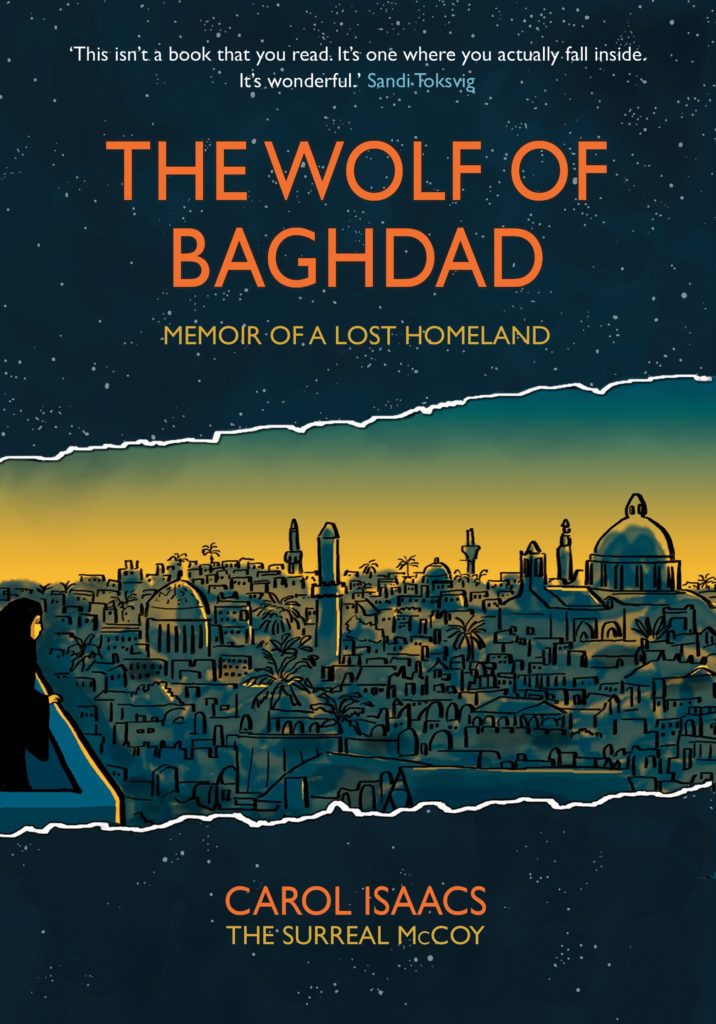

The Wolf of Baghdad begins with Carol Isaacs removing a box of family photographs from the shelf of her London flat, following which there are passport sized portraits of her ancestors along with quotes from or about them. She’s then visited by a ghost and emerges into the streets of the Baghdad her Jewish ancestors once lived in. Ghosts are embedded in the city, and as Isaacs follows them around she connects with the lives and routines of the past.

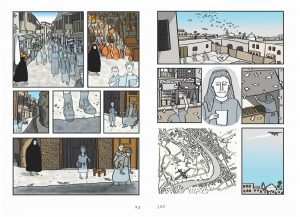

Instead of being needless repetition, illustrating the quotes gives them a greater weight and sense of place as they build into glimpses of a life gone by. A careful placement of those quotes leads readers through Baghdad, the left sample page reaching “The narrow alleyways were often flooded and for a few pennies a porter would carry you across”. The art alone would tell the story, but not the context of it being a daily trip to school. Isaacs’ keeps the pictures simple, yet detailed, always drawing attention to ambiance, providing wonder in small moments.

As pleasant as experiencing times gone by is, it’s midway before everything falls into place, and we’re told why the Isaacs family ended up in London. The Wolf of Baghdad isn’t just a family history, but an elegy for the former Jewish population of Baghdad. For centuries Jews formed a large percentage of the city’s residents, the integration with other cultures and religions complete. In 1940 Jews accounted for a third of the occupants, yet Iraqi support of Nazism during World War II changed that in a decade. The rise of nationalism meant persecution of Jewish businesses along the lines of what their German counterparts experienced in the 1930s, and over a decade almost the entire Jewish population departed Baghdad. The later timeline shows prejudice rearing its head in the 1930s also. Isaacs is a mute witness watching ghosts, conveying a terrible sense of loss poignantly and horrifyingly.

The title is explained at the beginning, relating folklore that a wolf would protect Jewish households from demons, leading to a tradition of a wolf’s tooth being attached to the cribs of babies. Yet it’s surely deliberate that the wolf at the door is also to be considered.

Despite the tragic events, there’s a warmth and humanity to the quotes and to the depiction of them, making for an educational experience that also supplies daily life. Twenty pages of afterword explanations, Isaacs remembering her childhood, history and contextualisation round off a beguiling package. If you’re wondering about the Surreal McCoy credit, it’s the alias Isaacs uses for her cartooning.