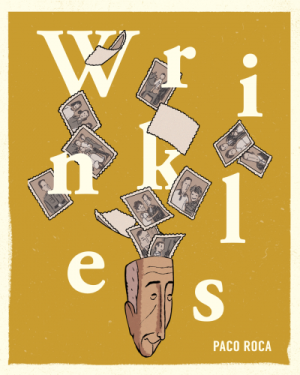

Review by Frank Plowright

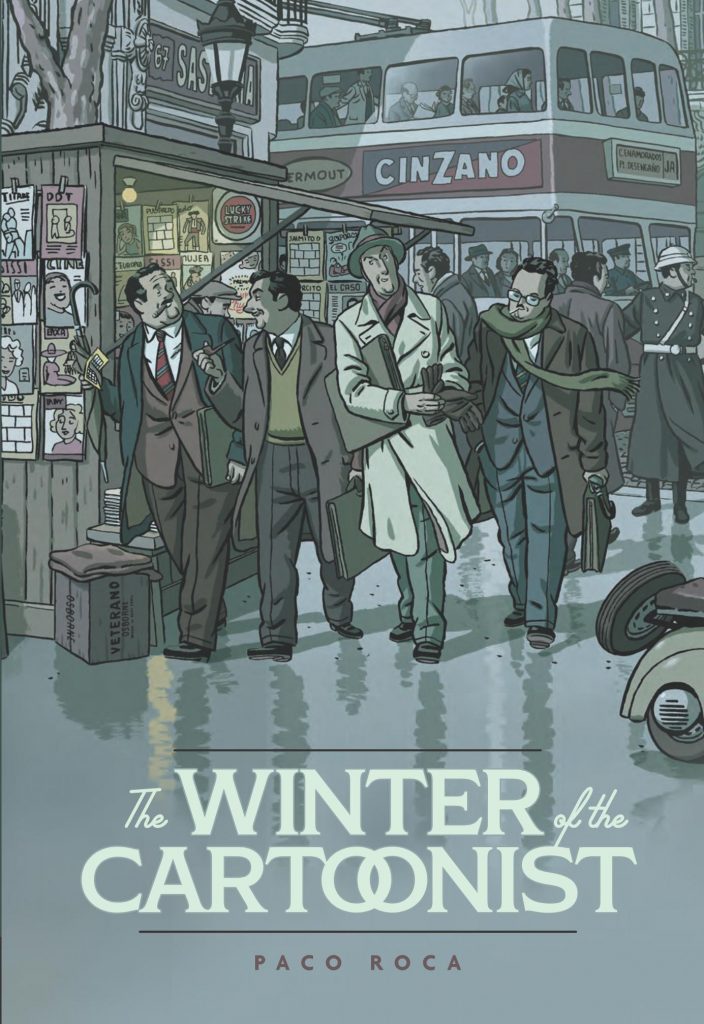

Several graphic novels have appeared in the 21st century in which creators mythologise their predecessors, the artists who influenced their work. At first glance The Winter of the Cartoonist appears another, but it’s set apart by virtue of taking place in Spain during the late 1950s, twenty years into the iron grip of the country’s fascist dictatorship. What is and isn’t permitted informs every aspect of creativity, and before publication every page of text or illustration has to be approved by the state censor.

It’s under those conditions that five star artists decide to leave the security of work with Spain’s leading magazine publisher to set up their own strip magazine Tío Vivo (Roundabout in English). This was in 1957, when Carlos Conti Alcántara, Guillermo Cifré, José Escobar, Eugenio Giner, and José Peñarroya were the driving force behind Pulgarcito (Tom Thumb), yet publisher Bruguera insisted they sign new contracts. Under the terms the cartoonists would sacrifice ownership of their characters and their art wouldn’t be returned to them.

Paco Roca’s examination of what happened begins with a chapter set in 1958 when most of the cartoonists return to Bruguera, before heading back to tell the story of their previous year, and thereafter continues to switch between 1957 and 1958. He uses imaginative storytelling methods, having the replacement cartoonists consider their place and security, or spotlighting the pressure on Bruguera editors, aware of company expectations, yet generally sympathetic to the ideals of the creators. Roca’s own illustration is a match for all the creators he names, precise, disciplined, good with likenesses and in evoking the period.

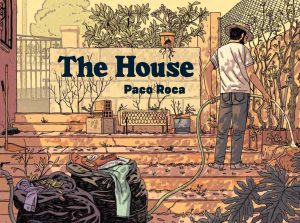

However, The Winter of the Cartoonist lacks the accessibility of Roca’s other projects translated into English (see recommendations). In the interests of accuracy there’s a considerable cast, yet even with Roca’s skill at defining them there are frequent instances when readers will have to pause to consider who someone is. That’s partly because among fans in Spain these are all artists with a formidable reputation, but they’re little known to the wider world. Roca’s Spanish audience also know the times their parents or grandparents lived through. In both cases assumptions of knowledge are suitable for that audience, but greater context is required abroad. Some comments are easily understood, such as those obliquely referring to the general poverty, but others require explanation. It would be nice to know, for instance, how the cartoonists raised the money to publish. It’s not as if space is at a premium, as Roca includes several scenes of them just shooting the breeze.

It’s a depressing story, and intended as such, one of corporate brutality reflecting the state as Roca switches between the optimism of the artists and the plans being hatched against them by their former employers. Parallels are easily drawn with the treatment of cartoonists in other nations. The geniuses who rejuvenated British children’s comics in the 1950s were equally exploited, but some at least managed to move on to higher paying work elsewhere. Incredibly slow progress has occurred at the US superhero publishers, and we should celebrate the success of Marvel artists in the 1990s managing what Roca’s forebears couldn’t and making a success of Image Comics.

Seen as a primer to a generation of Spanish cartoonists, Roca does a wonderful job, as looking up the work of everyone who merits an appendix entry is rewarding. However, despite the good art and a poignant ending, the dry tone, and missing context fights against maximum appeal.