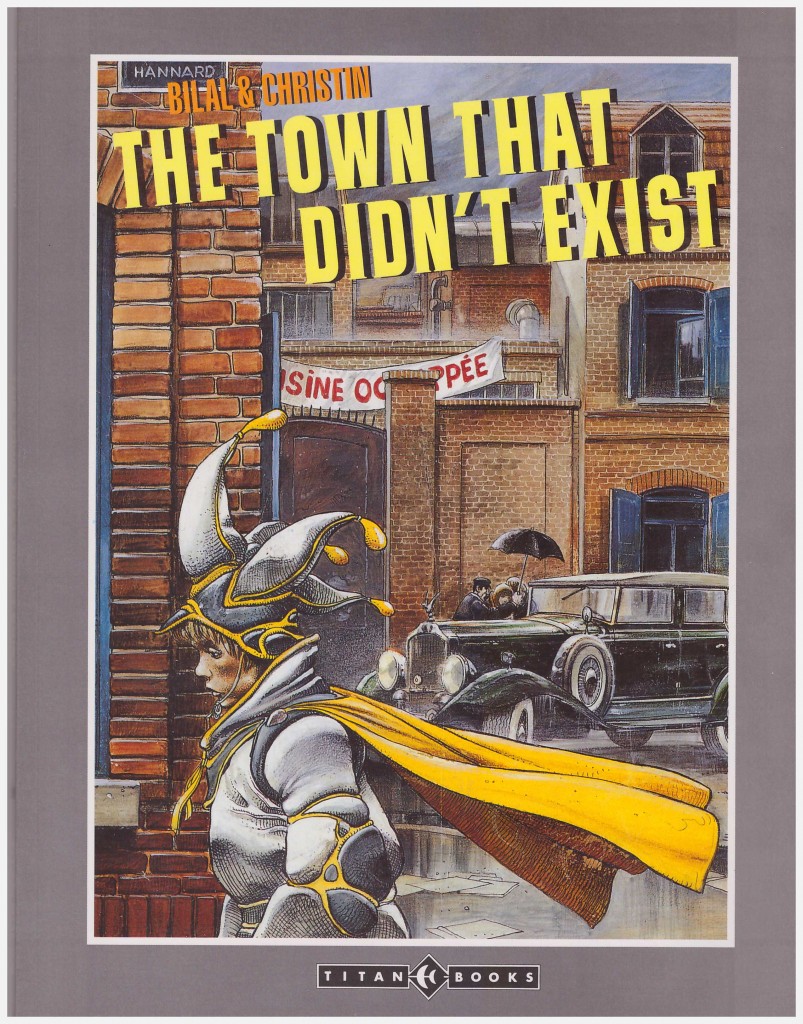

Review by Frank Plowright

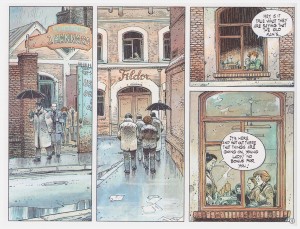

This is the third of Pierre Christin and Enki Bilal’s 1970s collaborations, and for 25 years the earliest of their works to be translated into English. It’s easy to see why. It’s linear, straightforward and largely lacking in the fanciful elements of their earlier work while presenting a skewed view on the industrial unrest prevalent in mid-1970s France. As such, it eclipsed most contemporary English language comics in tone and ambition. Also, by 1975 Bilal’s art had almost settled into his familiar style, with few cartoony touches remaining.

Jadencourt is a provincial French town in crisis. Sustained by sentimentality, it’s only viable due to the owner of several national businesses electing to continue factories in the place he founded his commercial empire, a town with few other resources. Aged 93, though, control has been ceded to the company directors who see a more profitable future elsewhere and aim to close the premises with the loss of 250 jobs. The inevitable consequence is a strike that’s lasted a month as the story opens.

When the old owner dies, his grand-daughter inherits control of the company structure. Wheelchair bound since a horse-riding accident in her teens, her views on corporate responsibility and benevolence vary wildly from the profit-hungry directors. She has her own vision for Jadencourt, and while willing to incorporate the views of all residents, Madeleine Hannard possesses her grandfather’s strength of will.

Christin’s starting point appears to be considering how the working population would react were they to be granted much of what they wish for. He concludes many would remain unsatisfied, the sacrifices required for a utopian way of life outweighing the benefits, and that snobbery and mistrust perpetuated for generations can’t be wiped away overnight. It’s a glimpse back into a world where industrial control wasn’t firmly in corporate hands, and agree with the conclusions or not, The Town That Didn’t Exist is a captivating and thought-provoking read.

While the 1989 paperback edition is perfectly acceptable, the 2003 hardback is richer for a more intuitive translation.