Review by Frank Plowright

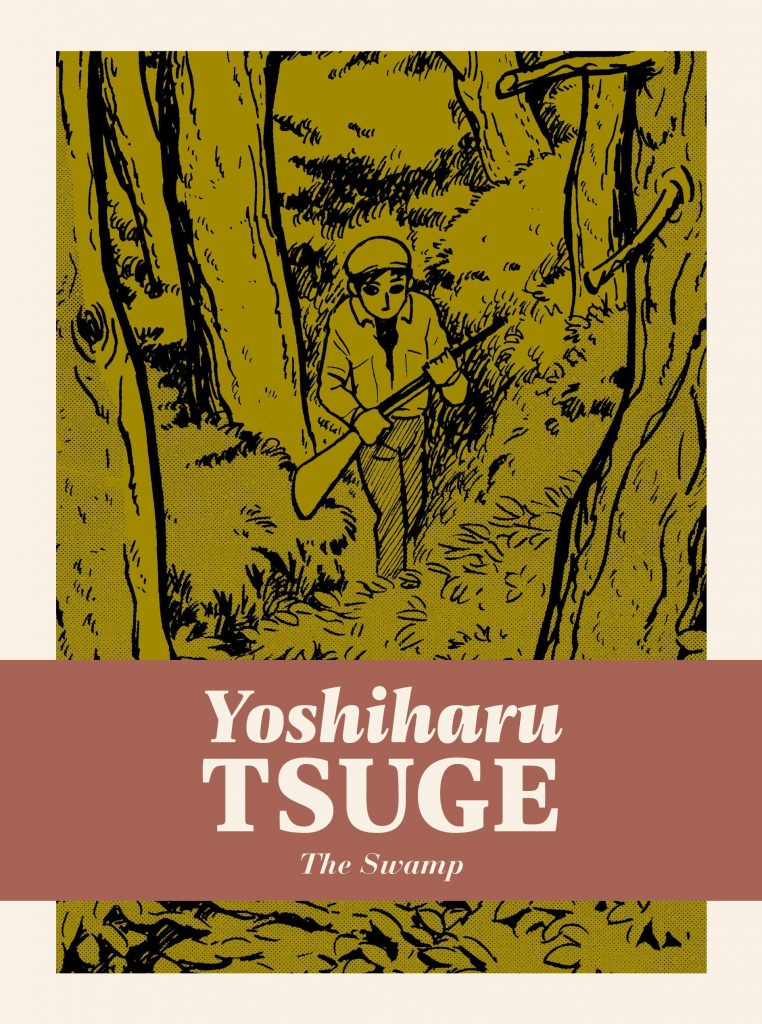

Japanese comics have been translated into English on a substantial scale since the 1990s, so the joy of reading The Swamp is twofold. Firstly it’s the joy of a smartly observational set of short stories largely remaining true to life, compactly and expressively drawn. The second joy is the thought that if it’s taken until 2020 to translate The Swamp, produced in the mid-1960s, how many phenomenal Japanese works remain unseen in English?

While it eventually goes into detail about the individual stories, it’s worth reading the first ten pages of Mitsuhiru Asakawa’s afterword before embarking on Tsuge’s work. It contextualises his development and the comics scene in which it occurred, and explains how a few cartoonists instituted a radical new approach where a person’s internal conflict becomes the narrative priority.

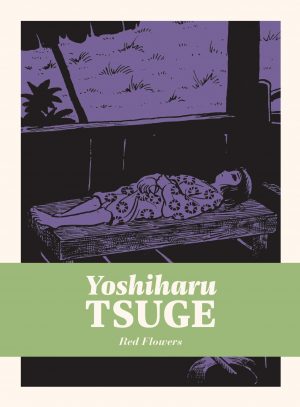

Drawn and Quarterly present Tsuge’s new work chronologically, starting in August 1965, and continuing until December 1966. The chronology is picked up in Red Flowers. Together they chart Tsuge’s development and the themes recurring in his work.

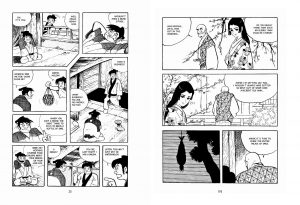

Opener ‘The Phony Warrior’ begins by evoking an early scene from Moby Dick when a traveller to a hot springs is asked to share a room with an intimidating stranger, but takes a different path. As a creative statement about what would follow it’s a tentative step as if Tsuge doesn’t want to depart too far from the status quo. The title discloses the revelation and motivations, and it features samurai, but it’s also unconventional, not heroic, with a slight ambiguity about the ending. Is the narrator also a phony? Samurai appear in a couple of later early tales, and while the sample art from ‘Watermelon Sake’ features standard comedy stylings, they’re well drawn and the story has a kick in the tail. That lack of predictability is well applied to a few later inclusions also, but they’re clever, and it’s possible to see Tsuge including elements reflecting his own life in them, most clearly in ‘The Unusual Painting’.

‘The Swamp’ has been chosen as the title story because it’s the first real step beyond for Tsuge, ambiguity, allegory and nihilism infusing a bleak tale of a dangerous hunter’s overnight stay. It’s a conflicting swirl of emotional turmoil, as is the following ‘Chirpy’, where the clever title couldn’t be further from the truth of this downbeat kitchen sink drama. Neither were well received on publication.

Tsuge’s also finding his way artistically, and these stories show experiments along the way to a definitive style that’s ironically almost there with the matter of fact nature of ‘The Phony Warrior’. There’s the darkly shaded realism of ‘The Second Hand Book’, the industrial grime of ‘The Strange Letter’, a grisly horror piece, and the attractive decorations of ‘The Ninjess’ (sample right), the longest story in The Swamp.

After a continual progression the closing ‘Handcuffs’ is a retrograde step, opening with several pages of standard crime drama. It never escapes that trap, despite a macabre use of amnesia as a plot device providing a very artificial form of tension. Asakawa’s afterword explains that it’s a reworking of a 1959 story written and laid out by Tsuge’s younger brother Tadeo, who’d also maintain a comics career, but it’s considerably weaker than the other stories. Asakawa further notes that three of them reworked earlier material, but these have a more compelling nature.

As entertaining as these stories are, they’re just a starting point, more than hinting at what’s to come, but not yet the full package. However, they’re compelling little dramas in their own right, well worth your time.