Review by Frank Plowright

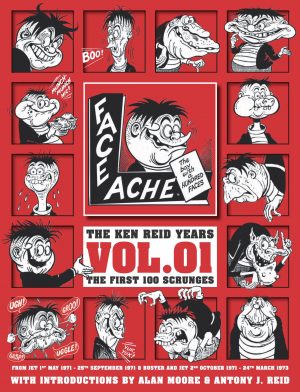

In 1964 Ken Reid ranked among the pre-eminent British humour strip artists, part of the new talent that had revitalised The Beano a decade before, making it Britain’s favourite comic. In terms of imagination, impact, innovation and influence it’s no overstatement to consider Reid and his colleague Leo Baxendale as equivalent to Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby. However, neither was entirely happy with the paternalistic and parsimonious attitude prevalent at The Beano‘s publishers, an indication of which is that when Reid finally jumped ship to create the strips for a new humour comic for London based Odhams, his page rate was doubled.

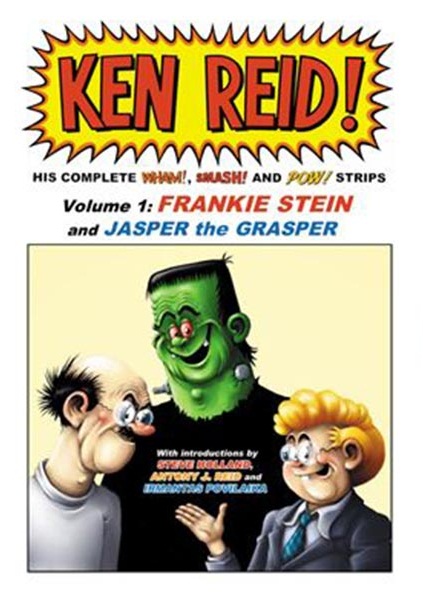

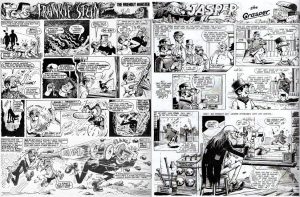

Moving to a new company Reid was also freed from sometimes overzealous editing, and he flourished at a new publisher whose brief was to ramp up his talent for the comically grotesque rather than tone it down. Always capable of creating the ugliest faces, he was inspired to let loose, and as the strips here progress, there’s a growing sense of the shackles being shed. The bulk of the book is occupied by Reid’s Frankie Stein strips. A scientific genius operating in suburban England creates a playmate for his young son, the result being the, good natured, well-intentioned and naive Frankie, also clumsy and with no awareness of his great strength. Cue calamity as the serene household is repeatedly plunged into crisis.

Reid’s astonishingly imaginative art may have been presented in British children’s comics, but has more in common with the American underground comics of the era, so these are still anarchic and surprising strips, cemented by Reid’s amazing talent for twisting faces. They’re targeted to delight by poking fun at pompous administrative figures, and there’s a certainty of an officious local authority gump ending up righteously embarrassed, if not fleeing in terror by the end of the strip. After almost a year of Reid writing his own scripts, Odhams employed one time Beano writer Walter Thorburn. His efforts begin as far more traditional and restrained, featuring time-tested reward finishes, and the acquisition of sweets or ice cream as plots. Among his earlier efforts the odd strip conceived by Reid really stands out, but even those written by Thorburn have a manic intensity due to Reid’s natural inclinations, and Thorburn gradually escapes the rigid formula of his earlier work.

A second strip also features, Jasper the Grasper, a Victorian era miser brilliantly designed in patched clothing, straggly hair cascading from beneath a battered top hat. Spread over two pages, it permitted Reid to be even more expansive with the art, but was dropped after six episodes, only to become very successful a few years later when drawn by Trevor Metcalfe. It’s another testament to excess, Jasper unstinting in his efforts to save a penny.

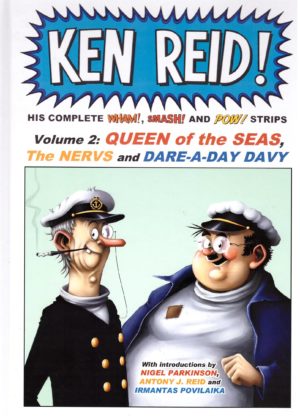

This is the first of two superbly produced hardcover volumes reprinting Reid’s entire output for Odhams between 1964 and 1968, collectively the peak of British humour comics during the 1960s. Reproduction is crisp despite being scanned from printed comics, and a comprehensive package is rounded out by wonderfully informative articles, Reid’s script notes, and some sketches. These collections aren’t available via Amazon, can be found on Ebay, but the best value is purchasing direct from a website set up by publisher Irmantas Povilaika. British readers of a certain age have waited decades for this labour of love, and it’s delightful to see Reid’s visionary work lives up to the memory.