Review by Frank Plowright

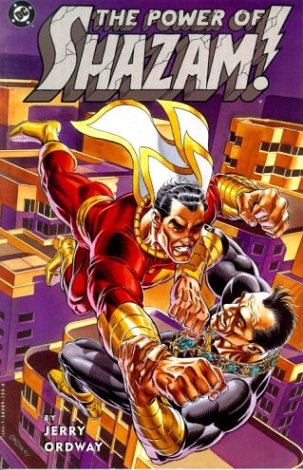

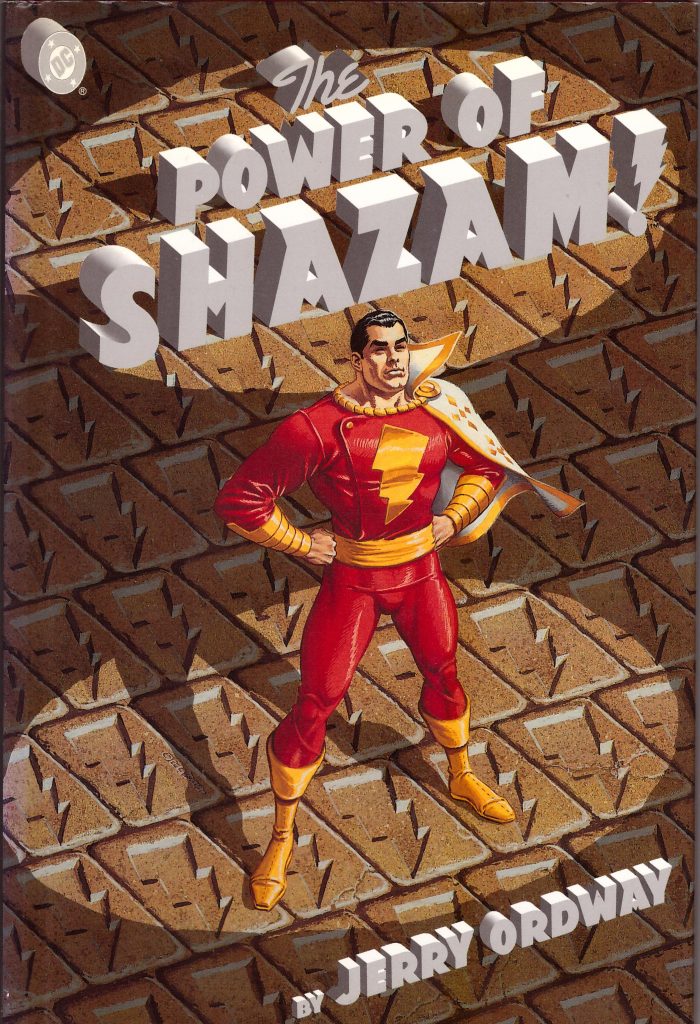

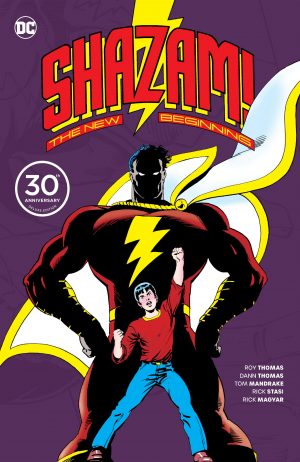

A 1970s revival for Captain Marvel had been launched with considerable fanfare, but never really caught on beyond an initial rush, the cartooning out of touch in the 1970s. It left a character who’d once outsold Superman relegated to occasional guest star appearances, with no-one entirely sure what to do with him. Roy Thomas considers why his 1980s version never took off in the introduction to Shazam!: The New Beginning, and Jerry Ordway applied the same approach of stepping away from traditional approach and presenting Captain Marvel and his world more realistically. The Power of Shazam launched Ordway’s four year run, the most successful iteration since the 1940s, and a longevity not bettered since.

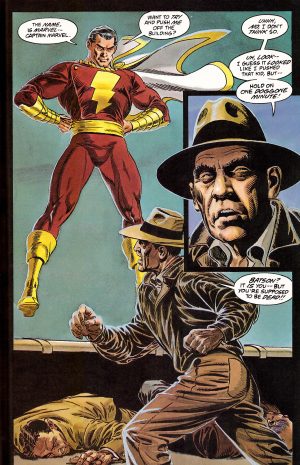

Ordway opens by revealing for the first time why Billy Batson is orphaned during a long scene in which his archaeologist parents are murdered. After that he moves to the known origin of newspaper boy Billy being led to an odd subway station where he’s gifted the powers of Shazam, and able to transform into the world’s mightiest mortal just by saying that name. Both scenes are long, given a gravitas, and dispense with lightheartedness that characterised Captain Marvel. Ordway doesn’t go over the top with explicit violence, but he moves the tone of the strip closer to traditional 1990s DC material. Among this a confused, angry and violent Captain Marvel immediately post-transformation strikes the wrong note, and the conversion of old mad scientist enemy Sivana into a corporate titan is too similar to Lex Luthor’s updating for Superman several years earlier. Offsetting this is the consideration applied to how Billy would cope with his new abilities, at first unaware of both his limitations and his own strength.

There’s a timeless veneer to Ordway’s art. He creates the appealing art deco surroundings of Fawcett City as a way of suggesting the past without committing to it, and he uses other locations to reinforce this, although the cars and other technology do cement an era as an imagined 1950s. Ordway’s storytelling is first rate, and he’s very good with facial expressions that don’t over-exaggerate.

Although a creatively successful updating when released, time has moved on, and it’s left a lot of fine looking artwork accompanying a story that lags behind. Ordway’s version of Black Adam is nowhere near the imperious character who’d later emerge, and while he deals well with the idea of a child in an adult’s body, some of the dialogue is now also of its time. Beware that this was always intended as the introduction to a series, and several plot threads are left dangling, resolved in stories never collected as a graphic novel.