Review by Frank Plowright

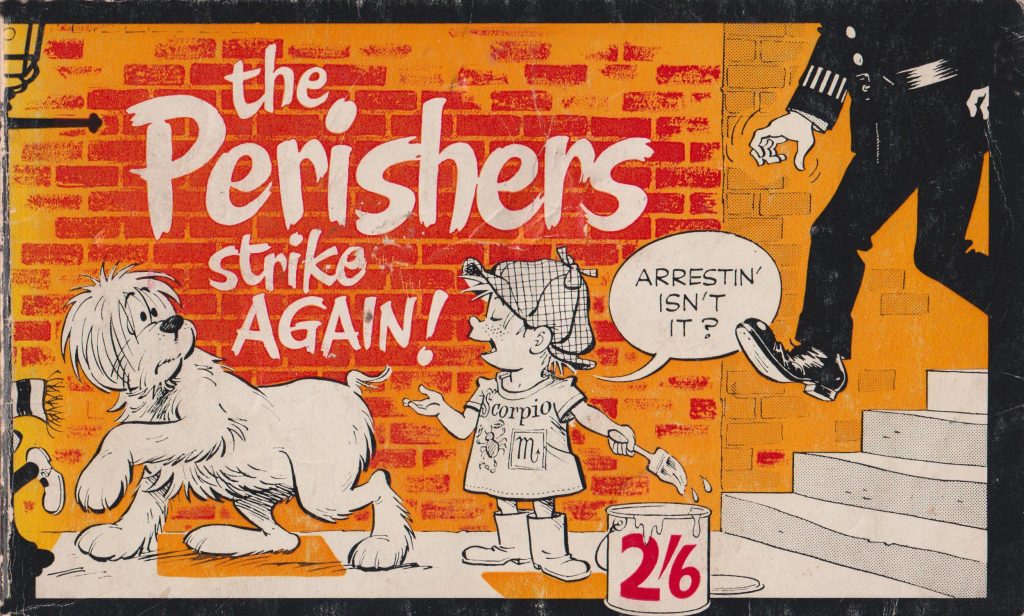

Covering The Perishers during 1961 and 1962, Maurice Dodd and Dennis Collins have already hit rare form with their combination of slapstick, occasional philosophy, great comedy timing and beautifully drawn characters. Horizons are starting to broaden, and new themes are introduced.

The annual summer holiday strips would become a fixture. A couple appeared in The Perishers, but there was an extended sequence in summer 1961, with more to follow in 1962, most consigned to The Perishers Back Britain. However, Dodd hasn’t yet conceived the landmark Eyeballs in the Sky topic. Other introductions include Maisie’s friend Plain Jane, the first recurring extension to the cast, although she’d never become a signature character, and the never named beetle and his wife.

Collins is already brilliantly expressive, every emotion the cast feel apparent in their faces, from a downbeat Wellington to an enraged Maisie. While for the most part he sells the jokes with detailed panache, there are occasional strips where he’s able to offer something more. When given strips concerning moonlight and reflections, Collins’ treatment of light and shade is breathtaking, and the strip finishes with some great silhouettes.

Having created a very individual voice for Maisie at the start, Dodd is toning her down a little here. She no longer drops her h’s at the start of words, but in common with the remainder of the cast, a g at the end of the word is likely to be absent. This wasn’t without precedent in British newspaper strips, where working class characters were seen, but remained consistent throughout the entire run.

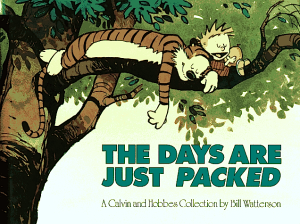

While the slapstick gags are exquisitely crafted with still funny punchlines, it’s the pondering on life that consistently raises The Perishers beyond the likes of Andy Capp, which ran alongside it in the Daily Mirror. Wellington is the strip’s chief philosopher. He and his sheepdog companion Boot contemplate each other’s intelligence, and Wellington is a source of creatively amusing money making schemes, his career as a cart salesman beginning here. Even funnier is another moneymaking scheme where he offers people the opportunity to hit him on the head with a mallet, assuming no-one will. Dodd plays this masterfully, subverting the assumption that Marlon’s too soft-hearted, but Maisie doesn’t lightly let money go.

Downsides? Once again, the strips are reprinted in themed batches rather than chronologically, and without great care. Strips of Maisie’s use of a mallet precede those of it being introduced in Wellington’s possession. In other places there are now dated references, not just the language, but in Marlon’s second hand Teddy Boy look, although Collins draws great winkle pickers. Anyone born after 1960 can look the term up. These are small prices to pay for page after page of hilarity.

A fair selection of these strips also appear alongside Dodd’s commentary in the first Perishers Omnibus, but many more only remain available in this book out of print since 1965. It’s tragic neglect of one of the all time great newspaper strips.